Recovery Act Third Quarterly Report - Tax Relief and Income Support Provisions

THE TAX RELIEF AND INCOME SUPPORT PROVISIONS OF THE RECOVERY ACT

An important aspect of the Recovery Act is the substantial direct contributions it has made to family incomes, through tax cuts, cash payments, and in-kind transfers. These resources account for over one-third of the total size of the Act, and roughly half of the stimulus under the Act in 2009.12 Payments to individuals and families were made through a number of programs, including one-time payments to seniors and retirees, the Making Work Pay tax credit, extensions and expansions of unemployment insurance benefits, and increases in benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. These payments have gone to over 95 percent of working families, helping them to maintain their consumption despite economic conditions that might otherwise have led them to pull back.

The direct contributions to family incomes represent economic stimulus just as much as do the other components of the Recovery Act. Because these payments went out very quickly—many within the first quarter after the Act was passed—and because recipients are likely to spend additional funds quickly, they pump dollars back into the economy while also reducing the strain on local governments to provide safety net services.

Equally important, for those families that have been directly affected by the recession through job loss, diminished retirement savings, or reduced income, Recovery Act assistance has helped them put food on the table, keep up with rent and mortgage payments, cover college tuition bills, and maintain health insurance coverage. And, because much of this support was provided through expansions of already-established programs, the Act was able to quickly funnel supplemental resources to families in need without additional application burdens or delays in enrollment processing.

The Components of the Recovery Act that Directly Affect Family Incomes

We begin by summarizing the most important individual tax credits and transfer programs in the Recovery Act. As discussed in Section IV.B, this list omits several additional ways in which the Act is supporting family incomes.

- The Making Work Pay (MWP) refundable tax credit provides wage earners with a credit up to $400 ($800 for joint filers) for the 2009 and 2010 taxable years. This credit is calculated at a rate of 6.2 percent of earned income and is phased out for individual taxpayers with an adjusted gross income of $75,000 and above and joint filers with an adjusted gross income of $150,000 and above. It was implemented through reductions in workers’ paychecks beginning on April 1, 2009. The Department of the Treasury Office of Tax Analysis estimates that over 100 million families will benefit from the Making Work Pay tax credit in 2010.13

- Relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) was extended for 2009, and the income threshold for exemption was increased. These changes are estimated to help over 26 million families avoid the AMT, which imposes higher tax burdens and substantial complexity on those who are subject to it.

- The Recovery Act significantly strengthened the unemployment insurance (UI) system in order to ensure that this critically important safety net would meet the needs of people who lost their jobs during the recession. As a result, almost all UI recipients receive an additional $25 per week in benefits through the Federal Additional Compensation program. In addition, an extension of the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program and additional federal funds for the Extended Benefits (EB) program provide for additional weeks of benefits to workers who have exhausted their benefits under the regular program but, due to the weak economy, are still out of work. Nearly 22 million people have benefited from the ARRA unemployment insurance benefits to date.

In its original form, these additional benefits were only available to those who lost their jobs in 2009. However, at the President’s urging, Congress extended this support to unemployment spells beginning through March 31, 2010. Congress has recently allowed the additional support to lapse, but the President is working with Congress to correct that situation in order to provide vital support to the unemployed and the economy as a whole.

- The Recovery Act provides a 65 percent subsidy to help people who have lost their jobs or have experienced reductions in hours to purchase health insurance through the COBRA program, thereby allowing individuals to maintain their insurance by paying only 35 percent of premiums. Recipients must have been terminated from employment between September 1, 2008 and December 31, 2009 to qualify. The ARRA was later amended to extend the period of termination to March 31, 2010 and the amount of time the subsidy may be claimed from 9 to 15 months. As with the UI provisions, Congress has recently allowed the COBRA subsidies to lapse, and the President is working with Congress to correct that situation.

- The Recovery Act appropriated about $20 billion to bolster the Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides vouchers for food purchases to households with low assets and gross monthly incomes below 130 percent of the poverty line (or approximately $28,700 for a family of four). The Act provides an automatic 13.6 percent increase in the SNAP allotment to all recipients, amounting to $80 per month for a household of four receiving the maximum benefit. The Recovery Act also eased eligibility requirements for unemployed, childless adults by temporarily eliminating time limits for benefit receipt. Largely because of the recession, national SNAP enrollment is at an all-time high, with caseloads increasing in every state (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2009). As of January 2010, 39.4 million individuals in 18.1 million households were receiving SNAP benefits.

- The Economic Recovery Payment (ERP) provides a one-time automatic payment of $250 to retirees, disabled individuals, and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) recipients. Over 50 million people have received ERP payments. In addition, certain Federal and State pensioners not eligible for Social Security benefits were eligible to receive the refundable $250 Government Retiree Credit (GRC) on their 2009 taxes.

- The Recovery Act created an Emergency Contingency Fund to support states facing large increases in costs under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. These funds can be used to support increased basic assistance benefits. States may also draw from the $5 billion fund to establish or expand programs that help TANF participants enter the labor market through subsidized employment, training, and work-study positions. An additional $319 million was appropriated for TANF supplemental grants to benefit those states with historically high population growth and low average benefits.

- An additional set of tax provisions aim to provide relief to a broad range of families. The ARRA temporarily increased the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for families with three or more children and for many married couples regardless of the number of children. Many families are also benefitting from expanded eligibility for the child tax credit during taxable years 2009 and 2010. The first $2,400 of unemployment benefits per recipient in 2009 were exempted from federal income tax. State and local sales and excise taxes on the purchase price of qualified vehicles were made deductible in 2009, while the refundable First-Time Homebuyer Credit was increased to $8,000 and extended. Finally, the partly-refundable American Opportunity education tax credit of up to $2,500 is helping individuals pay college-related expenses in 2009 and 2010.

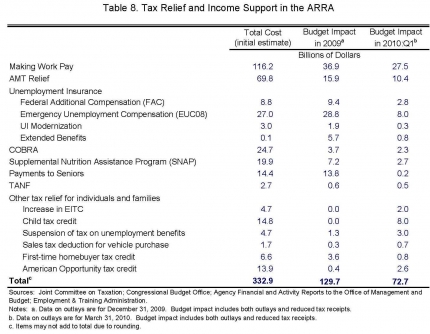

Table 8 summarizes the various programs. The first column lists the total cost of each program, as estimated in the initial analysis of the Recovery Act by the Joint Committee on Taxation and CBO. Together, over $330 billion was devoted to these programs providing tax relief and direct payments to individuals, over one-third of the entire ARRA package.14

The second column lists the outlays in each program through December 31, 2009. As noted above, tax cuts and payments to individuals are relatively easy to distribute quickly, providing rapid stimulus to the nation’s economy. Accordingly, over one-third of the total anticipated expenditure for these programs was distributed during calendar year 2009. Moreover, this understates the speed with which these programs were implemented, as a substantial portion of the tax expenditures in tax year 2009 will not be counted as having been outlayed until refund checks go out in the spring of 2010.

The third column of Table 8 shows the additional tax cuts and income support provided by the Recovery Act in the first quarter of 2010. As can be seen, outlays in this single quarter are over half as large as the total outlays in 2009. Much of this reflects refundable tax credits that are counted as outlayed when recipients file their 2009 tax returns in early 2010. There is a particularly large impact of the Making Work Pay tax credit in 2010:Q1, combining reduced withholding toward 2010 taxes with increases in refunds on 2009 taxes. The Office of Tax Analysis estimates that increased 2009 tax year refunds due to MWP will amount to $17.5 billion in 2010:Q1 and an additional $3.5 billion later in 2010.15

ARRA and Disposable Personal Income

Not every dollar that is spent by the Federal government on these programs flows directly into families’ bank accounts. Some of the funds included in Table 8, for example, went to States to fill the holes in their budgets left by increased demand for TANF benefits over the course of the recession. To understand the direct impact of the Recovery Act on family incomes, then, it is necessary to move beyond the Federal accounts. For this purpose, we turn to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) on the impact of the Recovery Act on disposable personal income. These data are only available through the fourth quarter of 2009.

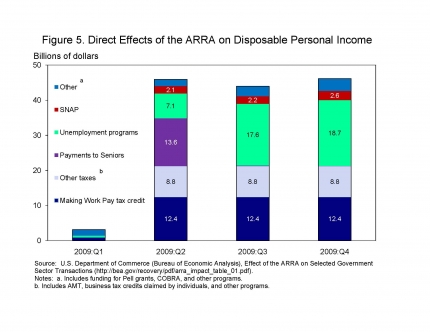

All told, the BEA estimates that the ARRA transfer payments and tax cuts that went directly to households raised disposable income by $139 billion. This is slightly higher than the total shown in Table 8; the difference is largely attributable to the inclusion of some small programs (such as business tax credits paid to business owners) in the BEA total that are not included in our Table.16 Figure 5 shows the distribution of the ARRA contribution to disposable income by quarter and category.

About one-quarter of the total payments came from the Making Work Pay tax credit. As noted earlier, for most families this credit was distributed via reduced withholding from their regular paychecks. Thus, its impact was spread evenly across the final three quarters of 2009.17 Another 19 percent came from other reductions in individuals’ taxes, including the AMT relief, the EITC, the child tax credit, and a variety of additional business tax incentives claimed by individuals. Payments to seniors, one-time $250 checks that went out in the second quarter of 2009, accounted for 10 percent. Most of the remainder of the impact came from provisions targeted specifically to individuals whose incomes had been directly impacted by the recession: nearly one-third through UI programs, and 5 percent through the SNAP.

The data in this chart is available to download as a csv file.

The BEA has not yet published comparable estimates for the first quarter of 2010. However, consistent with the large surge in tax relief and income support shown in Table 8, we expect the direct ARRA contribution to disposable personal income in the first quarter of 2010 to substantially exceed its direct contribution in any previous quarter.18

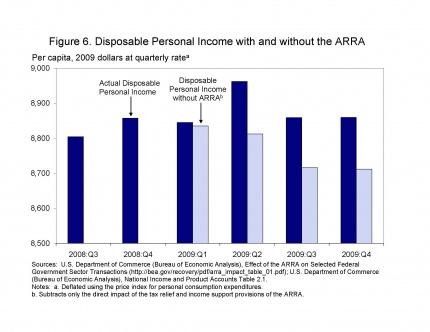

Figure 6 shows that the transfers and tax reductions made a dramatic difference in households’ purchasing power. The figure shows the behavior of actual per capita real disposable income since 2008:Q3 (the dark blue bars) and the same series minus the direct effects of the tax relief and income support provisions of the Recovery Act (the light blue bars). The light blue bars indicate that absent the family financial assistance provisions of the ARRA, real disposable incomes would have fallen throughout 2009.19 Instead, despite the severe impact of the recession, income in each of the last three quarters of 2009 actually surpassed its 2008:Q4 level. The difference was largest in the second quarter, when the one-time $250 Economic Recovery Payments were distributed, but even in the third and fourth quarter, household purchasing power was maintained at approximately the same level as in 2008:Q4 by the assistance provided under ARRA. This is a remarkable impact, particularly when one considers that job losses during the recession reduced private wage and salaries by $300 billion in 2009 relative to 2008.

The data in this chart is available to download as a csv file.

Extending Figure 6 through the first quarter of 2010 would again require data that the BEA has not yet published. However, from the continued rate of Recovery Act outlays in the quarter, we can confidently conclude that the pattern of ARRA impacts in Figure 6 continued through 2010:Q1. Put simply, the ARRA has continued to give vital support to families’ budgets.

It is important to note that the estimates shown in Figure 6 capture only the direct impacts of the financial assistance provisions on the families that received them. These families used their additional disposable income to support higher consumption than would have been possible without the Act, producing further indirect effects on personal income through the additional jobs (and higher wages) created at firms from which the direct recipients purchased goods and services. Many of the financial assistance provisions were designed to go to families facing temporary financial challenges; as we discuss below, these families are likely to have spent the money they received particularly quickly, producing disproportionate indirect effects. To take one example, the Department of Agriculture estimates that 97 percent of SNAP benefits are redeemed within 30 days of issuance.

On top of this, the components of the Recovery Act that did not go directly to families—infrastructure investments, state fiscal relief, and other direct federal spending—had their own impacts on economic activity, strengthening the demand for labor and increasing individual employment and earnings. As discussed in Section III, the CEA estimates that about 2 million people had jobs in 2009:Q4 due to the Recovery Act, and the compensation that those individuals received is not credited to the Act in the BEA’s accounts.20 In short, the path that disposable personal income would have followed over 2009 without the Recovery Act would have involved even steeper falls than shown by the light blue bars in Figure 6, which subtract only the direct impact of the Act’s tax relief and income support provisions.

Who Is Being Helped?

The analysis above focuses on the average impact of the ARRA financial assistance provisions. This impact dramatically understates the importance of the ARRA for families that were directly impacted by job losses. The unemployment insurance, nutritional assistance, and health care provisions were all targeted to families facing periods of low income. Many of these families were able to avoid eviction and keep food on the table only due to the availability of assistance under the Recovery Act. By contrast, other provisions (for example, the payments to seniors and the Making Work Pay tax credit) were more widely spread across the population.

To understand the overall distributional impact of the financial assistance provisions in the Recovery Act, we turn to individual-level data on the receipt of payments under various programs from the Annual Social and Economic Survey conducted in March of each year under the aegis of the Current Population Survey (CPS). This provides information on roughly 100,000 households each year, and asks each to report total income from a variety of sources for the previous calendar year. Data describing income in calendar year 2009 were collected in March 2010 and will not be available for analysis until later in the year. Thus, for a preliminary look at the distribution of ARRA payments, we use data from the March 2009 survey, describing income and transfer receipts in 2008, and project these forward to 2009.21

We focus on four programs that are most amenable to analysis in the available data: payments to seniors, the Making Work Pay tax credit, the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, and unemployment insurance benefits. Together, these account for 80% of the 2009 outlays summarized in Table 8. 22

The distribution of eligibility for the payments to seniors and the Making Work Pay tax credit is unlikely to have changed much between 2008 and 2009, so the 2008 data likely can be used to provide a quite accurate picture of their impacts. The payments to seniors are the simplest to simulate: using detailed information about each person’s age and income sources, we assign the Economic Recovery Payment and the Government Retiree Credit to any individual who would have been eligible if these payments had been available in 2008. For the ERP, this includes adults with income from Social Security, SSI, retirement income for railroad workers, or veteran’s payments for retired or disabled individuals; for the GRC, individuals with Federal, state, or local pension income who did not receive the ERP. It is similarly straightforward to simulate family eligibility for the Making Work Pay tax credit, which depends primarily on earned income and Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). 23 We adjust the simulated frequencies we obtain from the CPS to ensure the aggregate expenditures by state match administrative data from the Social Security Administration for the ERP and Office of Tax Analysis estimates for the Making Work Pay tax credit.24

The SNAP and unemployment insurance provisions in the ARRA are somewhat harder to simulate, as the declining economy made many more people eligible for benefits under these programs in 2009 than in 2008. The most recent available data, from January 2010, indicate that more than one in eight U.S. residents—39.4 million individuals in 18.1 million households—are enrolled in the SNAP. This represents an increase of 11.9 million individuals since the start of the recession in December 2007.25 Similarly, around 11 million households are now receiving UI benefits, far more than the roughly 3 million recipients in December 2007. Unfortunately, we have relatively little information about how the characteristics of new recipients of benefits under these programs compare with those of the recipients in 2008.

For the SNAP, we rely on information in the CPS about SNAP recipiency at the household level and assume that the recipients in 2009 resemble the recipients in 2008 in their family incomes, education, and geographic distribution.26 For unemployment insurance benefits, we take advantage of additional data from the monthly CPS survey that is already available for each month of 2009. By comparing data from 2009 and 2008, we can measure changes in the prevalence of unemployment for demographic groups defined by race, education, age, and sex. We assume that the prevalence of unemployment insurance receipt has changed similarly, and modify the distribution of UI receipt in the annual 2008 data to reflect these changes.27 As in our analysis of the MWP and ERP, we make a final adjustment to ensure that our estimates match the distribution across states of UI and SNAP expenditures in 2009.

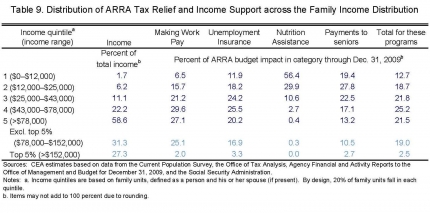

Table 9 shows how the payments under the four programs are distributed across family income groups. As discussed above, the Making Work Pay tax credit went to 95 percent of working families. 6.5 percent of these tax cuts went to families in the bottom quintile of the income distribution, reflecting the lower labor force participation rates of these families and the low earnings of those who do work. The credits are more evenly distributed across the other four quintiles, though the distribution varies slightly because there are more dual earners in the higher income groups. For the top quintile, Table 9 splits the results into those for the families in the top 5 percent of the income distribution and those in the remainder of the top quintile. By design, the tax credit does not go to very high-income earners. Overall, the MWP tax credit is highly concentrated in families earning between $12,000 and $152,000.

The distribution of unemployment insurance expenditures is similar to that for the MWP tax credit (though a bit more evenly distributed across income quintiles), as families in all income categories have experienced elevated rates of unemployment during this recession. By contrast, SNAP payments are heavily skewed toward the bottom of the income distribution, with over half going to families in the bottom income quintile. 28

The right-most column of Table 9 shows the overall distribution of tax credits and payments under the four programs. About one-eighth of tax credits and payments went to the lowest-income fifth of families, about seven times the share of total income accruing to these families. The second, third, and fourth quintiles—one definition of the middle-class—also each received larger shares of ARRA payments than their shares of aggregate income. The top income quintile received 22 percent of ARRA payments, less than half its share of income. Only 2.5 percent of ARRA payments went to families in the top 5 percent of the income distribution, less than one-tenth of this group’s share of income.

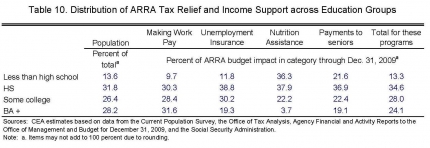

Table 10 repeats the analysis to examine the distribution of payments across education groups. Not surprisingly, MWP tax credits are roughly evenly distributed across the top three education groups while those with less than a high school degree receive relatively less money from this program, reflecting their relatively lower employment rates and earnings. UI payments disproportionately flow to the middle education groups. Nutrition assistance flows primarily to the least-educated individuals, while payments to seniors are also somewhat skewed (though less so than SNAP) toward the lower end of the education distribution, reflecting the relatively lower education levels among older cohorts. Across the four programs, the distribution of payments quite closely mirrors the population distribution, with per capita payments only a bit higher in the middle education categories than at the top and the bottom.

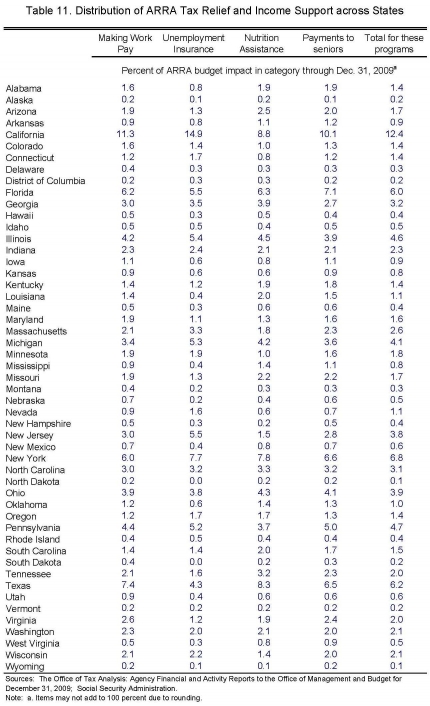

Finally, Table 11 presents the distribution of tax cuts and income support payments across the fifty states plus the District of Columbia. The most important finding is that these benefits have been spread broadly. The table also shows several expected patterns. States with larger populations—for example, California, Texas, and New York—receive more funds than states with smaller populations. States with relatively elevated unemployment rates—for example, California, Michigan, and Nevada—receive relatively more money from the UI programs in the ARRA, while states with higher poverty rates—for example, Mississippi and Louisiana—receive more money from SNAP. And Florida, with its disproportionate number of retirees, receives relatively more money under the payments to seniors programs. Overall, the distribution of Recovery Act funds closely reflects the size and characteristics of the states.

Consumption Expenditure and ARRA Tax Relief and Payments to Individuals

Over the year ending in the last quarter of 2008, real personal consumption expenditures fell by more than in any comparable period for more than 50 years. After this terrible drop, household spending leveled off during the first half of 2009 and began to rebound during the last two quarters of the year. This is consistent with the timing of the tax relief and income support components of the Recovery Act, which largely took effect beginning in the second quarter of 2009. Here, we attempt to quantify the role of these components in halting the free-fall in household spending, and by doing so, contributing to the turnaround in GDP growth and employment.

The effects of the Act’s tax relief and income support provisions came in two ways. First, as described above, it added about $130 billion to aggregate household income in 2009; we refer to the household spending caused directly by this extra income as the “direct effect” of the income support provisions of the Act. Second, that extra spending translated into higher sales for some businesses, which were then able to avoid layoffs or increase hiring, adding to their employees’ labor income and creating a virtuous feedback cycle. We refer to the increase in economic activity attributable to this feedback as the “induced” effect. This section of the report provides estimates of both the direct effect and the “total effect” (that is, the sum of the direct and induced effects).

CEA Model. This approach of calculating separately the direct, induced, and total effects differs from the approach taken in the CEA macroeconomic model described in Section III.C (and in previous CEA reports). The “CEA model” (as we will refer to the model of Section III.C) can be described, using our new terminology, as having assigned “total effect” coefficients (or a “total multiplier”) to each of the different types of fiscal stimulus based on prior empirical estimates from the macroeconomic literature. For example, the model uses estimates of the total multiplier of permanent tax cuts as the total multiplier for the Making Work Pay tax credit (which, though only legislated for two years, was widely perceived to likely be permanent), and uses estimates of the total multipliers associated with temporary tax cuts to estimate the total effects of transfers to seniors. (Another total multiplier is used for transfers such as unemployment insurance payments and SNAP payments; for details, see CEA, 2009a, 2009b). Because of its focus on the overall effects, the CEA model only shows the total impact on GDP and employment; it does not provide estimates of the impact on spending.

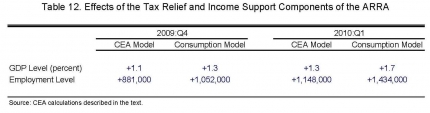

Using these total multipliers along with the spending pattern for the categories shown in Table 8, the first column of Table 12 shows the CEA model’s estimated effects on GDP and employment as of 2009:Q4.29 The CEA model implies that the income components of the ARRA had raised GDP by 1.1 percent, and employment by nearly 900,000 jobs, relative to what would have happened without the Recovery Act. By 2010:Q1, the effect reached 1.3 percent of GDP and more than 1.1 million jobs. (Recall that these figures do NOT include the effects of other ARRA components; they represent only the effect of the individual tax relief and income support components of the Act.)

Consumption Model. That literature, in fact, provides compelling empirical evidence that household spending responds strongly and quickly to tax cuts and other income support measures like those in the Recovery Act.30 While the existing estimates of this response are not very precise, several lessons from the research literature are clear:

- Household spending responds more strongly to income changes that are perceived to be permanent than to one-time payments.

- But the response to one-time payments is much larger than would be expected from idealized models in which household spending depends only on very-long-run considerations (like lifetime income).

- Low-income households have a higher propensity to spend than high-income households.

- Low-asset households (especially those who might find it difficult to borrow) have a higher propensity to spend than households with more assets.

To distill this research into a form that can be used to estimate the Recovery Act’s spending effects, we have assumed that the Act’s tax relief and income support programs can be grouped into three categories: long-term changes (the Making Work Pay tax cut); one-time payments and temporary tax changes (the Economic Recovery Payments, the Government Retiree Credit, AMT relief, and the other tax relief provisions for individuals in Table 8); and income support payments targeted to those facing difficult economic circumstances (unemployment insurance payments, SNAP payments, COBRA, and TANF). We treat each of these categories differently.

Recent work by Parker, Souleles, Johnson, and McClelland (2010; hereafter, PSJM) estimates that on average, for each dollar of one-time stimulus payment received, households spend about 25 cents more on nondurable goods within one quarter of the date of receipt of the stimulus funds. In the next quarter, nondurable spending remains higher than it would have been (absent the stimulus payment) by about 15 cents.31 The paper does not provide an estimate of spending effects beyond the second quarter. Earlier work by Johnson, Parker, and Souleles (2006) found that about two-thirds of tax rebate payments in 2001 were spent within a year of receipt.

Because the literature has found that the timing of the spending effects is difficult to pin down statistically, our principal focus is on the effects on consumer spending over all of 2009. We assume that in response to a transitory stimulus payment of 1 dollar, the total additional spending in the quarter of receipt and the following three quarters is 50 cents.32 This is broadly consistent not only with the estimates in PSJM and Johnson, Parker, and Souleles (2006), but also with standard estimates from the macroeconomic literature (see, for example, Campbell and Mankiw, 1989, 1991). The full details of our assumptions are given in the Appendix.

There are considerably fewer studies of the spending effects of long-term changes in taxes, partly because the data required to perform such studies (long-term changes in spending and taxes for individual households) are scarce. However, a substantial body of research has examined the response of spending to other kinds of permanent changes in income. That research has typically found that within a few years, spending seems to have more or less fully adjusted to changes to income (see Jappelli and Pistaferri, 2010, and the references therein). These results are roughly consistent with the theoretical literature that implies a one-year response of spending to permanent changes in income of 75 to 92 cents on the dollar (Carroll, 2009).

Other research, however, suggests that the response of spending to permanent shocks is not instantaneous (Campbell and Deaton, 1989; Carroll, Otsuka, and Slacalek, 2006). Consistent with these results, we assume that, for each $1 of a long-term tax cut, spending over the subsequent 9 months will be higher by about 60 cents. (We are mainly interested in a nine month period because the first long-term ARRA tax cuts did not have much effect until the second quarter of 2009, and we wish to estimate the effect for 2009 as a whole; for details see the Appendix.)

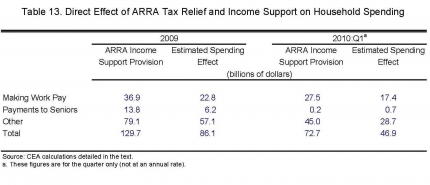

The left-hand panel of Table 13 presents our estimates of the direct effects on consumption of each of the major income support components of the Recovery Act for 2009 as a whole, along with the size of the corresponding income change. All together, our method estimates that the direct effect of these provisions was to boost household spending by about $86 billion dollars over the course of 2009.

This effect more than accounts for the recovery of consumption spending in 2009. Real consumption spending (in 2009 dollars) was $44 billion higher in 2009 than its level (at an annual rate) in the last quarter of 2008. Given our estimate that the direct impact of the tax relief and income support in the Recovery Act on consumption was $86 billion, it follows that without the Act, consumption would not have rebounded.

Table 13 also shows our estimates for the first quarter of 2010. As discussed above, the Recovery Act made large contributions to household income in that quarter as families benefited from the tax credits in the Act. Together with the spending dynamics from the extra income in 2009, the $73 billion in tax relief and income support in 2010:Q1 directly raised household spending by $47 billion (not at an annual rate), according to the model.33

The Differences between the Estimates. What accounts for the differences between the CEA model’s estimates of the effects of the tax and income support provisions and those that we obtain by examining the impact of the programs directly? The estimates in Table 13 include only the direct consumption spending effects from the programs, and not the induced effects from the increase in aggregate demand that also contribute to the total multiplier. To construct an apples-to-apples comparison of the two estimates, we use the quarterly pattern of consumption increases implicit in Table 13, and assume that the multipliers associated with direct household spending match the total multipliers for direct government spending assumed in the CEA model.

The comparison for 2009:Q4 is given in the first two columns of Table 12 above. The table shows that the microeconomic assumptions discussed above (given in the column labeled “Consumption Model”) imply that GDP was higher by 1.3 percent and employment was higher by nearly 1.1 million jobs relative to what would have happened absent the tax and income support provisions of the ARRA. These estimates are roughly 20 percent higher than those shown in column 1 for the CEA model. For 2010:Q1, the consumption model’s assumptions suggest that GDP was higher by 1.7 percent and employment by 1.4 million jobs because of the Recovery Act’s tax reductions and income support provisions, about one-quarter higher than those shown in column 3 for the CEA model. Given the degree of uncertainty surrounding all of these estimates, the results are reasonably close, but suggest that the CEA model may have been somewhat too conservative in estimating the effects of personal transfers and tax relief.34

The comparison for 2009:Q4 is given in the first two columns of Table 12 above. The table shows that the microeconomic assumptions discussed above (given in the column labeled “Consumption Model”) imply that GDP was higher by 1.3 percent and employment was higher by nearly 1.1 million jobs relative to what would have happened absent the tax and income support provisions of the ARRA. These estimates are roughly 20 percent higher than those shown in column 1 for the CEA model. For 2010:Q1, the consumption model’s assumptions suggest that GDP was higher by 1.7 percent and employment by 1.4 million jobs because of the Recovery Act’s tax reductions and income support provisions, about one-quarter higher than those shown in column 3 for the CEA model. Given the degree of uncertainty surrounding all of these estimates, the results are reasonably close, but suggest that the CEA model may have been somewhat too conservative in estimating the effects of personal transfers and tax relief.

12 See Table 2, which shows total 2009 spending under Individual Tax Cuts, AMT Relief, and Aid to Directly Impacted Individuals of $130 billion out of a total budget impact in the calendar year of $261 billion.

13 See Table 2, which shows total 2009 spending under Individual Tax Cuts, AMT Relief, and Aid to Directly Impacted Individuals of $130 billion out of a total budget impact in the calendar year of $261 billion.

14 The ultimate cost of these programs may be lower or higher, as the cost of tax provisions depends on the number of people who actually claim the credit or deduction, and the cost of income support programs such as UI and SNAP depends on the number of people who actually enroll in the programs. As the table indicates, the unemployment insurance programs outlayed more money in calendar year 2009 than the original estimate for the entire life of the programs, due to unexpected increases in unemployment.

15Consistent with this, the IRS reports that average tax refunds through March 12 were up $266 from the prior year. See White House (2010).

16Other such programs include ARRA funding for Pell grants. On the other side of the ledger, the BEA data exclude the TANF payments and UI modernization funds, as each were paid to States rather than individuals, and the First-Time Homebuyer Tax Credit, which the BEA classifies as a capital transfer; but these do not fully offset the additional programs in the BEA data that are not in Table 8. Another difference is that while Table 8 relies on the most current OTA revenue estimates for the tax provisions (for example, the Making Work Pay tax credit), the BEA calculations have not yet incorporated recent revisions. Finally, the BEA estimates may differ due to adjustments for the timing and territorial coverage of the ARRA.

17The BEA estimates for 2009 include only the portion of Making Work Pay distributed through reduced paycheck deductions in 2009; the portion distributed through refunds on families’ 2009 tax returns in early 2010 is not included in Figure 5. OTA estimates that $21 billion in tax-year 2009 MWP credits will be paid as income tax refunds in 2010.

18 The impact of 2009 tax refunds in the BEA data will be smaller than in Table 8, as the Table reflects the OTA estimate of the reduction in tax receipts and increase in refunds in 2010:Q1 due to the ARRA while the BEA instead spreads any effects on tax refunds over the entire 2010 calendar year.

19 Adding up the shortfalls in the four quarters of 2009, average incomes would have been $354 below what would have occurred had incomes continued at their 2008:Q4 rate throughout 2009.

20Further, some of the state fiscal relief was surely used to prevent tax increases and cuts in income support programs. These actions directly affected family income, but are not included in the calculations in Table 8 and Figure 6.

21We restrict our analyses to exclude single individuals under age 18 and full-time college students under 24.

22The largest program not included in our analysis is the Alternative Minimum Tax. The CPS data do not provide enough detail about families’ tax returns to permit simulation of AMT obligations. It is safe to assume, however, that the AMT provisions in the ARRA disproportionately benefitted families in the upper portion of the income distribution (see, for example, the Tax Policy Center, 2009a and 2009b, which finds that over 80% of the spending on the ARRA AMT provision went to tax filing units in the upper quintile of the income distribution). Our analysis will thus somewhat understate the share of benefits received by such families.

23We assume that married couples file jointly and that everyone else files as single. For applications where we want to consider the individual distribution of MWP credits, we assume that any credits earned by married couples are split evenly across the two people. For this analysis, we do not distinguish between MWP credits received through reduced payroll deductions in 2009 and those received as tax refunds in 2010.

24 Data on state level expenditures for the GRC are not available, and we do not adjust these.

25 Statistics reflect caseloads in the week ending March 13, 2010. This comparison combines increases in recipiency of regular UI benefits with expanded eligibility for UI through Extended Benefits (EB) and Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC). In the regular UI program, recipiency has risen from about 3 million to about 5 million.

26When we want to consider the distribution of benefits at the individual level, we assume that SNAP support is split evenly across all members of the household.

27Specifically, we divide individuals into cells defined by race (white non-Hispanic and all others), education (four categories), 10-year age groups, and sex. For each cell, we use data from the monthly CPS survey to compute the fraction of individuals who were unemployed, first in 2008 and then in 2009. We interpret the ratio of these two fractions as an indication of the increase in the prevalence of UI in each cell between years, and use this ratio to reweight the distribution of observed UI receipt in 2008 in the March 2009 CPS data. We assume that ARRA expenditures on UI are split evenly across all recipients, as we are unable to simulate separately the eligibility for extended and emergency benefits.

28Table 9 indicates that over three percent of SNAP payments went to families in the upper 40 percent of the income distribution. This may reflect higher-income families who fell on hard times and became eligible for SNAP for a portion of the year, or higher-income families sharing households with lower-income SNAP beneficiaries; we are unable to apportion SNAP benefits accurately across families in the same household.

29To maintain comparability with the discussion in Section III.C, this analysis uses the spending totals from Table 8, derived from the Agency Financial and Activity Reports submitted to the Office of Management and Budget. The results are similar if we instead use the categories and amounts from the Bureau of Economic Analysis shown in Figure 5.

30See Parker, Souleles, Johnson, and McClelland (2010) or Jappelli and Pistaferri (2010) for recent surveys of the literature.

31PSJM also find that spending on durable goods (mostly new motor vehicles) may have increased by even more than spending on nondurable goods, though previous work by Johnson, Parker, and Souleles (2006) did not find a statistically significant effect of the 2001 stimulus on durable goods spending. To be cautious, we leave out any effect of the stimulus payments on durables purchases. Including such effects would of course further increase our estimates of the Recovery Act’s impact on spending.

32One important form of one-time payments was the Economic Recovery Payments received by Social Security beneficiaries. PSJM find that older households had a higher propensity to spend the 2008 stimulus payments than did younger households; since the ERP payments were mostly received by older households, this could lead us to underestimate the spending effect.

33 The spending dynamics from the 2009 payments are the reason that the spending effect of the payments to seniors in 2010:Q1 are larger than the amount of payments in the quarter.

34The empirical literature on multipliers does not yield any robust conclusion about how the size of multipliers differs for government spending versus private consumption spending. In the absence of such evidence, the most transparent choice is to assume that the multipliers are the same. One concern with this assumption is that the import content of government purchases may differ from the import content of household consumption. In this case, the numbers for the consumption model in Table 12 should be multiplied by the ratio of the domestic content of household consumption to the domestic content of government purchases. An extreme lower bound for this ratio would be to assume that all government purchases occur domestically and all imports go into household consumption; this yields a ratio of 0.81 for 2009 (because total imports divided by consumption equals 0.19). This assumption would bring the estimates from the consumption model very close to those from the CEA model. However, more than half of all imports are intermediate goods, which would mean that less than 10 percent of consumption spending is on foreign final goods (implying a ratio of about 0.9). Further, some imports are investment goods and some final import spending is done by the government. For further information, see the BEA 2007 Import Matrix available at http://www.bea.gov/industry/more.htm.