McAllen Redux

Posted by on June 04, 2009 at 10:50 AM EST

Last Thursday I blogged on Atul Gawande’s New Yorker essay on McAllen, Texas – the little Texas town with the dubious honor of being one of the most expensive health care market in the country. As Dr. Gawande noted, in 2006 Medicare spent about $15,000 per enrollee here – close to twice the national average, and three thousand dollars more per person than McAllen’s per capita income of $12,000.

Over the past week, the example of this Texas border town has remained in my mind, and I became increasingly interested in this extreme case of regional variation in healthcare costs. As a lover of data, I asked my friend at the Dartmouth Atlas Group, Jonathan Skinner, if there was more there that he could tell me about the McAllen phenomenon. What he showed me was striking.

First, while McAllen is currently a major cost outlier, this wasn’t always the case. As recently as 1992, healthcare costs in McAllen were comparable to costs in El Paso, a county and city 800 miles down the border with similar demographic characteristics, and to the national average.

Over the next decade and a half, the respective Medicare service utilization patterns changed dramatically between these two markets. While El Paso continued to track just below national averages for per capita Medicare expenditures, McAllen’s per capita expenditures grew to nearly twice the national average – driven primarily by local norms that tend towards heavier use of discretionary services – such as diagnostic testing and surgical versus less invasive interventions – for which there are no clear clinical guidelines.

.jpg)

.jpg)

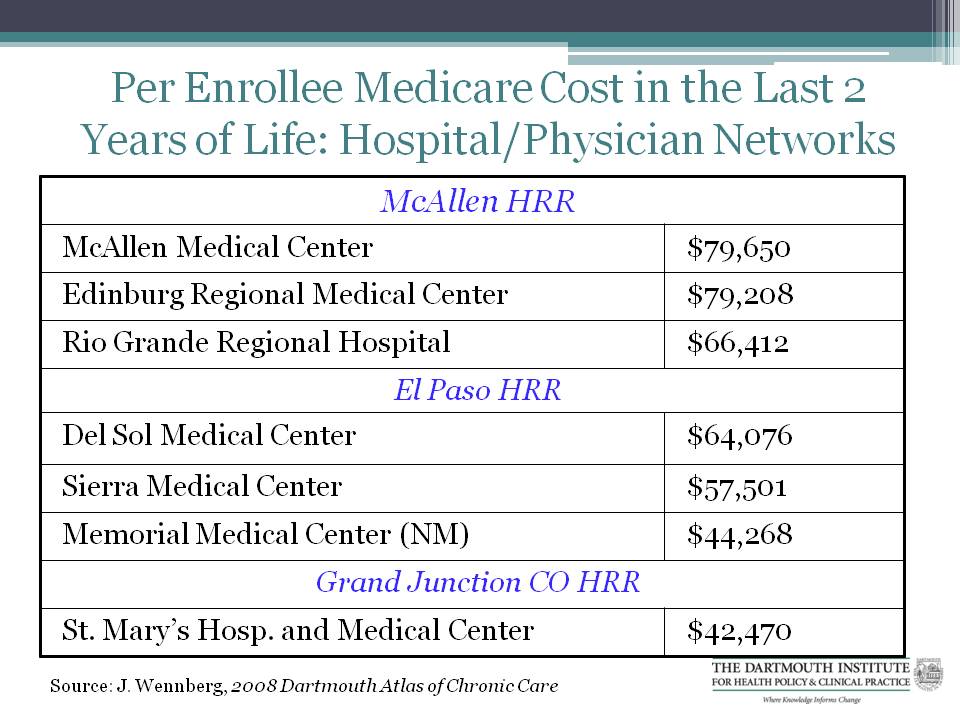

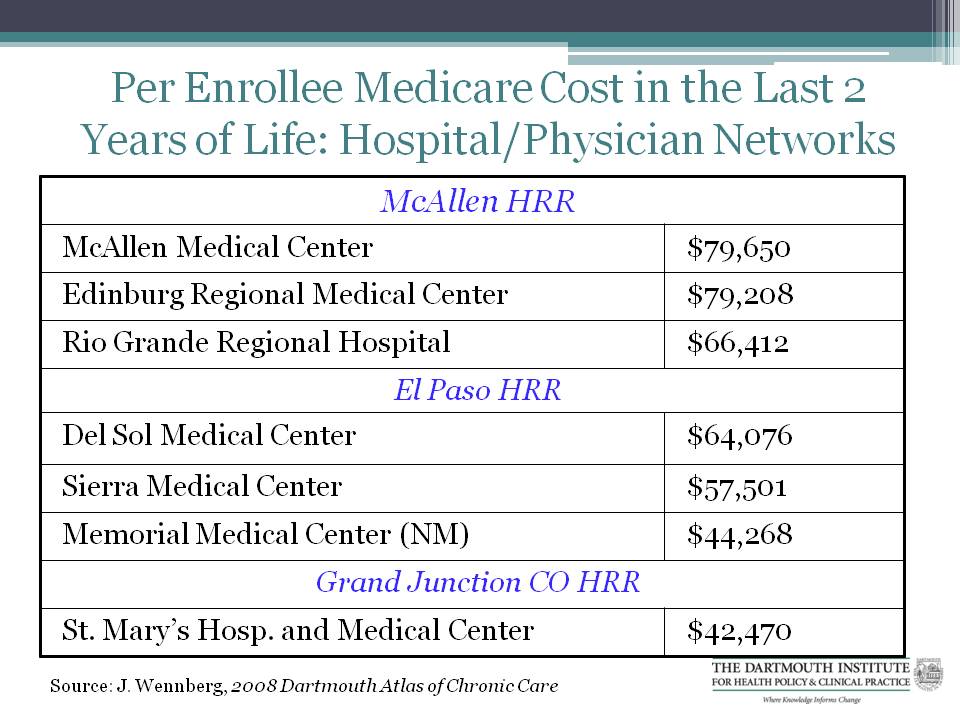

For example, at the end-of-life, nearly half of all McAllen Medicare patients see 10 or more physicians, significantly more than the national rate of 30 percent (and in Grand Junction, Colorado, it is just 11% – more than four times less than the rate in McAllen). Also, McAllen’s Medicare patients have 50 percent more cardiac surgery procedures as the national average (about 24 per 1000, versus about 16 per 1000), four times the ambulance spending during end-of-life, and eight times the home health care costs. Medicare spending per enrollee in the last two years of life also varies greatly among McAllen and other peer hospitals:

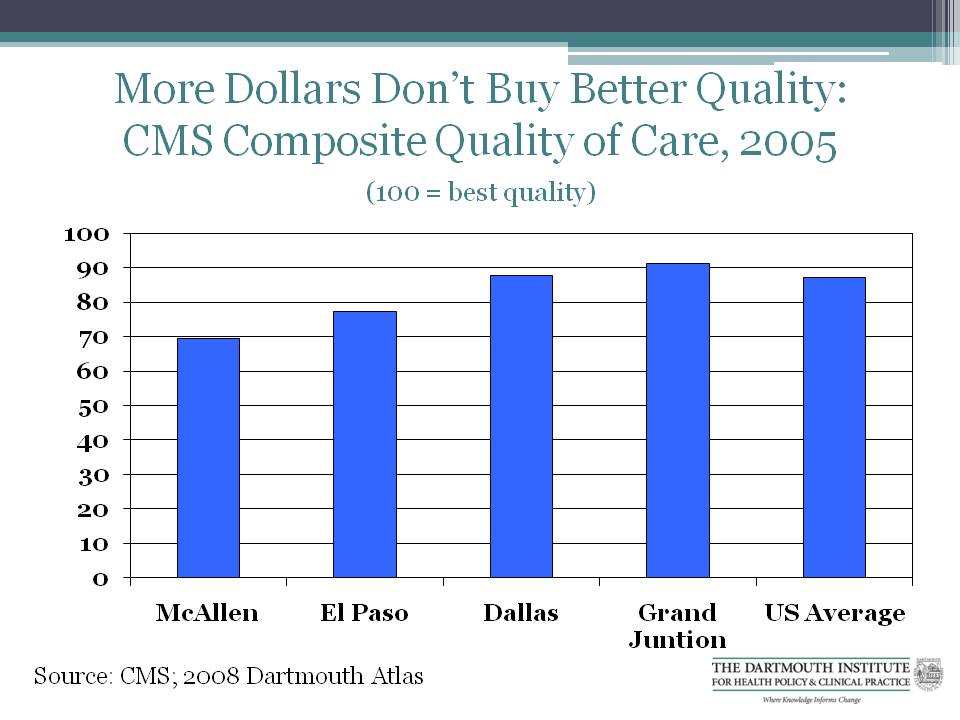

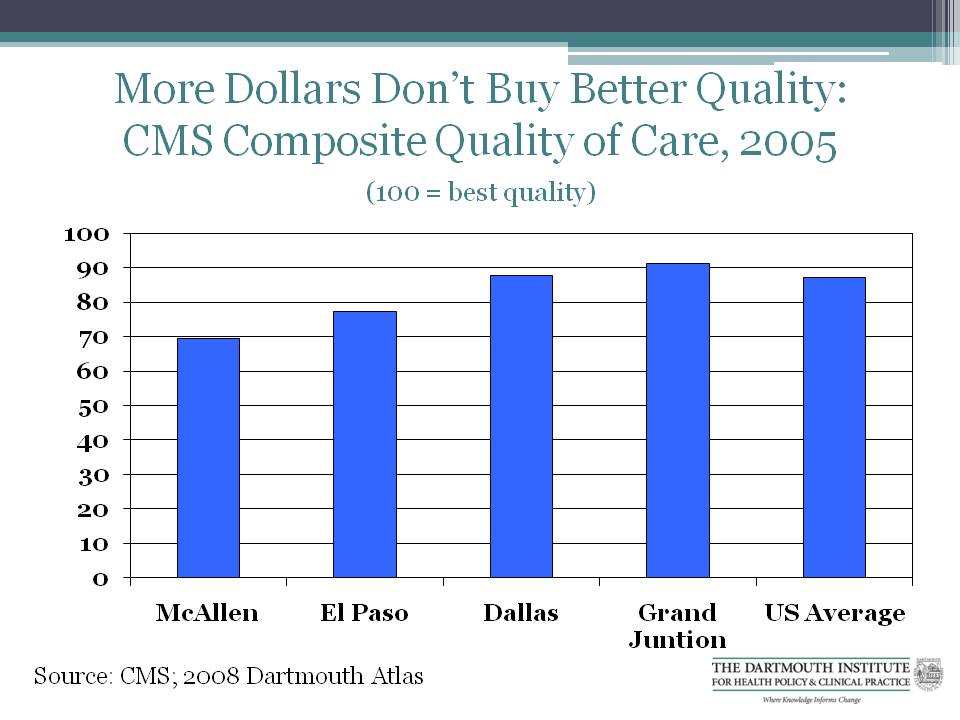

But all of this money doesn’t seem to buy the Medicare Beneficiaries of McAllen markedly better health or better quality care. While the 4.7 percent mortality rate in McAllen is slightly below El Paso (5.0 percent) and the national average (5.1 percent), it is on par with much lower cost Grand Junction. According to CMS’s Composite Quality of Care ratings McAllen’s score is about 70; lower than Texan peers El Paso and Dallas, about 18 points below the US average, and about 22 points below Grand Junction.

Medicine is practiced differently across regions, cities, towns, even hospitals. As patients, we hope that this variation is driven by norms of practices that provide us with the best and most appropriate care for what ails us. But in looking at an example like McAllen, Texas – a town where Medicare care costs have risen disproportionately relative to national and local benchmarks, and very quickly – it is hard not to ask what our return is on this high-taxpayer investment. From what we can measure, it’s not better health. It is simply more care.

Over the past week, the example of this Texas border town has remained in my mind, and I became increasingly interested in this extreme case of regional variation in healthcare costs. As a lover of data, I asked my friend at the Dartmouth Atlas Group, Jonathan Skinner, if there was more there that he could tell me about the McAllen phenomenon. What he showed me was striking.

First, while McAllen is currently a major cost outlier, this wasn’t always the case. As recently as 1992, healthcare costs in McAllen were comparable to costs in El Paso, a county and city 800 miles down the border with similar demographic characteristics, and to the national average.

Over the next decade and a half, the respective Medicare service utilization patterns changed dramatically between these two markets. While El Paso continued to track just below national averages for per capita Medicare expenditures, McAllen’s per capita expenditures grew to nearly twice the national average – driven primarily by local norms that tend towards heavier use of discretionary services – such as diagnostic testing and surgical versus less invasive interventions – for which there are no clear clinical guidelines.

.jpg)

.jpg)

For example, at the end-of-life, nearly half of all McAllen Medicare patients see 10 or more physicians, significantly more than the national rate of 30 percent (and in Grand Junction, Colorado, it is just 11% – more than four times less than the rate in McAllen). Also, McAllen’s Medicare patients have 50 percent more cardiac surgery procedures as the national average (about 24 per 1000, versus about 16 per 1000), four times the ambulance spending during end-of-life, and eight times the home health care costs. Medicare spending per enrollee in the last two years of life also varies greatly among McAllen and other peer hospitals:

But all of this money doesn’t seem to buy the Medicare Beneficiaries of McAllen markedly better health or better quality care. While the 4.7 percent mortality rate in McAllen is slightly below El Paso (5.0 percent) and the national average (5.1 percent), it is on par with much lower cost Grand Junction. According to CMS’s Composite Quality of Care ratings McAllen’s score is about 70; lower than Texan peers El Paso and Dallas, about 18 points below the US average, and about 22 points below Grand Junction.

Medicine is practiced differently across regions, cities, towns, even hospitals. As patients, we hope that this variation is driven by norms of practices that provide us with the best and most appropriate care for what ails us. But in looking at an example like McAllen, Texas – a town where Medicare care costs have risen disproportionately relative to national and local benchmarks, and very quickly – it is hard not to ask what our return is on this high-taxpayer investment. From what we can measure, it’s not better health. It is simply more care.

White House Blogs

- The White House Blog

- Middle Class Task Force

- Council of Economic Advisers

- Council on Environmental Quality

- Council on Women and Girls

- Office of Intergovernmental Affairs

- Office of Management and Budget

- Office of Public Engagement

- Office of Science & Tech Policy

- Office of Urban Affairs

- Open Government

- Faith and Neighborhood Partnerships

- Social Innovation and Civic Participation

- US Trade Representative

- Office National Drug Control Policy

categories

- AIDS Policy

- Alaska

- Blueprint for an America Built to Last

- Budget

- Civil Rights

- Defense

- Disabilities

- Economy

- Education

- Energy and Environment

- Equal Pay

- Ethics

- Faith Based

- Fiscal Responsibility

- Foreign Policy

- Grab Bag

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- Innovation Fellows

- Inside the White House

- Middle Class Security

- Open Government

- Poverty

- Rural

- Seniors and Social Security

- Service

- Social Innovation

- State of the Union

- Taxes

- Technology

- Urban Policy

- Veterans

- Violence Prevention

- White House Internships

- Women

- Working Families

- Additional Issues