Answers to Frequently Asked Questions about Marijuana

Answers to some of the commonly asked questions in the discussion about marijuana in the United States.

- What is the Federal response to state marijuana initiatives?

- Isn’t marijuana generally harmless?

- Is marijuana addictive?

- Doesn’t everyone use marijuana?

- What are the trends in marijuana use in the United States?

- What are state laws pertaining to marijuana?

- What is the difference between decriminalization, legalization, and medical marijuana?

- Is the government putting people in jail/prison for using marijuana?

- Why is the Federal Government opposed to medical marijuana?

- Does the government block research on marijuana?

- Wouldn’t legalizing marijuana remove a major source of funding for Mexican drug trafficking organizations?

- Couldn’t legalizing and taxing marijuana generate significant revenue?

- What impact does marijuana cultivation have on the environment?

Q. What is the Federal response to state marijuana initiatives?

In enacting the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), Congress determined that marijuana is a Schedule I controlled substance. In 2012, voters in Colorado and Washington state also passed initiatives legalizing marijuana for adults 21 and older under state law. As with state medical marijuana laws, it is important to note that Congress has determined that marijuana is a dangerous drug and that the illegal distribution and sale of marijuana is a serious crime. The Department of Justice (DOJ) is committed to enforcing the CSA consistent with these determinations. On August 29, 2013, DOJ issued guidance to Federal prosecutors concerning marijuana enforcement under the CSA. The Department’s guidance is available on the DOJ web site, and provides further detail.

Q. Isn’t marijuana generally harmless?

No. Marijuana is classified as a Schedule I drug, meaning it has a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States. The main active chemical in marijuana is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, more commonly called THC. THC acts upon specific sites in the brain, called cannabinoid receptors, starting off a series of cellular reactions that ultimately lead to the “high” that users experience when they smoke marijuana. Some brain areas have many cannabinoid receptors; others have few or none. The highest density of cannabinoid receptors are found in parts of the brain that influence pleasure, memory, thinking, concentrating, sensory and time perception, and coordinated movement.

Marijuana’s “high” can affect these functions in a variety of ways, causing distorted perceptions, impairing coordination, causing difficulty with thinking and problem solving, and creating problems with learning and memory. Research has demonstrated that among chronic heavy users these effects on memory can last at least seven days after discontinuing use of the drug.

These aren’t the only problems connected to marijuana use. Research tells us that chronic marijuana use may increase the risk of schizophrenia in vulnerable individuals, and high doses of the drug can produce acute psychotic reactions. Researchers have also found that adolescents’ long-term use of marijuana may be linked with lower IQ (as much as an 8 point drop) later in life.

We also know that marijuana affects heart and respiratory functions. In fact, one study found that marijuana users have a nearly five-fold increase in the risk of heart attack in the first hour after smoking the drug. A study of 452 marijuana smokers (but who did not smoke tobacco) and 450 non-smokers (of either marijuana or tobacco) found that people who smoke marijuana frequently but do not smoke tobacco have more health problems, including respiratory illnesses, than nonsmokers.

All that stated, a recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found that low levels of marijuana use (with no tobacco use) produced no detrimental effect in lung function among study participants. In fact, exposure led to a mild, but not clinically significant, beneficial effect—albeit among those who smoked only one joint per day. While these findings have received wide attention from the media and from advocates of marijuana legalization, it is important to consider them in the context of the extensive body of research indicating that smoking marijuana is harmful to health. Additionally, while the study did not include a sufficient number of heavy users of marijuana to confirm a detrimental effect of such use on pulmonary function, the findings suggest this possibility.

The harms of marijuana use can also manifest in users’ quality of life. In one study, heavy marijuana users reported that the drug impaired several important measures of health and quality of life, including physical and mental health, cognitive abilities, social life, and career status.

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. In 2011 alone, more than 18 million Americans age 12 and older reported using the drug within the past month. Approximately 4.2 million people met the diagnostic criteria for abuse of or dependence on this drug. This is more than pain relievers, cocaine, tranquilizers, hallucinogens, and heroin combined.

There are very real consequences associated with marijuana use. In 2010, marijuana was involved in more than 461,000 emergency department visits nationwide. This is nearly 39 percent of all emergency department visits involving illicit drugs, and highlights the very real dangers than can accompany use of the drug.

And in 2011, approximately 872,000 Americans 12 or older reported receiving treatment for marijuana use, more than any other illicit drug. Despite some viewpoints that marijuana is harmless, these figures present a sobering picture of this drug’s very real and serious harms.

Marijuana places a significant strain on our health care system, and poses considerable danger to the health and safety of the users themselves, their families, and our communities. Marijuana presents a major challenge for health care providers, public safety professionals, and leaders in communities and all levels of government seeking to reduce the drug use and its consequences throughout the country.

Yes. We know that marijuana use, particularly long-term, chronic use or use starting at a young age, can lead to dependence and addiction. Long-term marijuana use can lead to compulsive drug seeking and abuse despite the known harmful effects upon functioning in the context of family, school, work, and recreational activities.

Research finds that approximately 9 percent (1 in 11) of marijuana users become dependent. Research also indicates that the earlier young people start using marijuana, the more likely they are to become dependent on marijuana or other drugs later in life.

In 2011, approximately 4.2 million people met the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for marijuana abuse or dependence. This is more than pain relievers, cocaine, tranquilizers, hallucinogens, and heroin combined. In 2011, approximately 872,000 Americans 12 or older reported receiving treatment for marijuana use, more than any other illicit drug.

The research is clear. Marijuana users can become addicted to the drug. It can lead to abuse and dependence, and other serious consequences.

Q: Doesn’t everyone use marijuana?

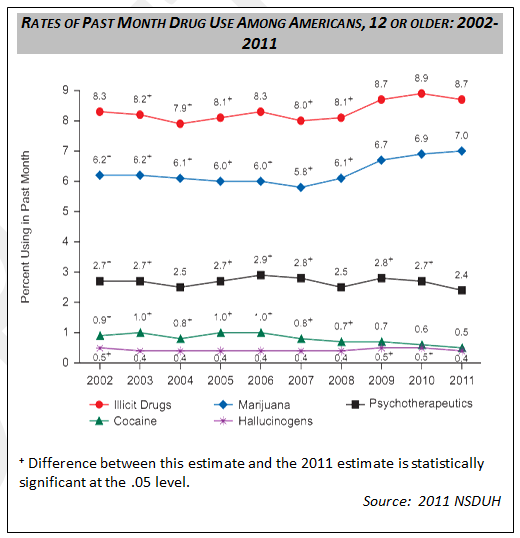

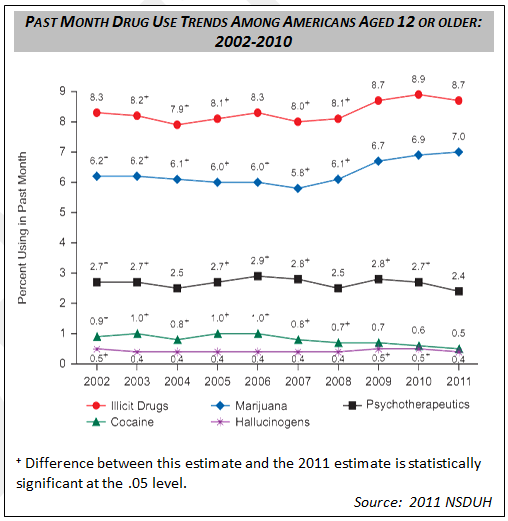

The vast majority of Americans do not use marijuana. While marijuana is the most commonly abused illicit drug in the United States, that does not mean everyone uses it. In 2011, more than 18 million Americans aged 12 and older reported using the drug within the past month. However, this is only 7.0 percent of the entire U.S. population 12 and older.

The vast majority of Americans do not use marijuana. While marijuana is the most commonly abused illicit drug in the United States, that does not mean everyone uses it. In 2011, more than 18 million Americans aged 12 and older reported using the drug within the past month. However, this is only 7.0 percent of the entire U.S. population 12 and older.

Furthermore, a majority of Americans have never even tried marijuana. The latest survey of drug use found that 58 percent of Americans 12 and older had never used marijuana.

Common references and media discussions about marijuana issues may create a perception that marijuana use is common, but the data show a very different picture.

Q. What are the trends in marijuana use in the United States?

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States.  In 2011, 18.1 million Americans aged 12 and older (7.0 percent) reported using the drug within the past month.

In 2011, 18.1 million Americans aged 12 and older (7.0 percent) reported using the drug within the past month.

While these figures are similar to levels reported in 2010 (6.9 percent) and 2009 (6.7 percent), they are a significant increase over rates reported in 2002 through 2008. In fact, between 2007 and 2011, the rate increased from 5.8 to 7.0 percent, and the number of users increased from 14.4 million to 18.1 million.

Survey data also tell us the frequency with which Americans are using marijuana. In 2011, 16.7 percent of Americans 12 or older who had used the drug in the past year did so on 300 or more days within the past 12 months. This translates into 5.0 million people using marijuana on a daily or almost daily basis over a 12-month period.

In 2011, approximately 2.6 million Americans aged 12 or older used marijuana for the first time. This averages out to about 7,100 new marijuana users every day. While relatively unchanged from the past few years, it is a higher number of people than is estimated in the early- and mid-2000s.

The average age of individuals between 12 and 49 who first use marijuana was 17.5 years old in 2011. This data point is an important one to understand, as earlier initiation of marijuana use is associated with a higher likelihood of needing treatment in the future. In 2011, among adults aged 18 or older, age at first use of marijuana was associated with illicit drug dependence or abuse. Among those who first tried marijuana at age 14 or younger, nearly 13 percent were classified with illicit drug dependence or abuse, higher than the 2.0 percent of adults who had first used marijuana at age 18 or older.

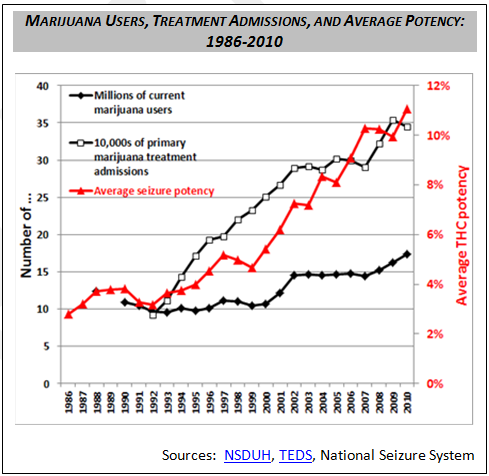

Over the last two decades, treatment admissions for marijuana have increased significantly. In 1992, approximately 93,000 people were admitted to treatment with marijuana as the primary drug for which treatment was needed.

By 2010, these admissions were estimated at 353,000. Only admissions for opiate prescription drugs and methamphetamine showed greater increases over the same period of time; however, admissions for both of these drugs in 2010 were about a half or less of marijuana admissions.

This increase in admissions for marijuana coincides with a similarly sharp rise in the potency of marijuana. In 1992, the average potency (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content) of marijuana seized by the government was about 3 percent. By 2009, the average potency had more than tripled to about 11 percent (see figure).*

*Source: Marijuana Potency Monitoring Program, University of Mississippi, Quarterly Report #115, Dec 19, 2011 (unpublished data).

Recent Trends in Youth Marijuana Use

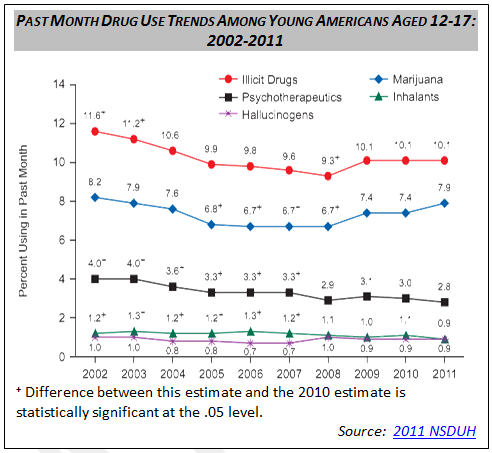

While the trend over the last 10 years has been largely positive, there have been some troubling increases in the rates of marijuana use among young Americans in the recent years.

After a steady decline and flattening in the prevalence of past month use of marijuana among youth (12 to 17 year olds) from 2002 through 2008, the rate increased from 6.7 percent in 2008 to 7.9 percent in 2011.

Other surveys show us similar trends. The Monitoring the Future study found that there has been an upward trend in use over the past three to five years among 10th and 12th graders. Because most drug users use marijuana either by itself or in combination with other substances, marijuana typically drives the trends in estimates of any illicit drug use. Not surprisingly, then, the trends in past-month use of marijuana mirror the trends for past-month use of any illicit drug:

- Past-month use of marijuana among 10th graders increased from 13.8% in 2008 to 17.6% in 2011.

- Past-month use of marijuana among 12th graders increased from 18.3% in 2006 to 22.6% in 2011.

-

Moreover, drug use has increased among certain youth minority populations since 2008

- Illicit drug use has increased by 43 percent among Hispanic boys and 42 percent among African American teen girls since 2008.

These data on marijuana use are of particular concern since trends in the perception of harm of smoking marijuana also have been declining over the same period of time. Prior research indicates that declines in these perceptions are predictive of increases in use.

Long-term Trends in Youth Marijuana Use

It is important to examine recent trends in marijuana use within the context of longer term trends. Despite some changes in survey methodology and differences from survey to survey, we can view a fairly accurate picture of youth marijuana use over the last 40 years.

- Data showed substantial increases in youth marijuana use during the 1970s, reaching a peak in the late 1970s.

- Surveys then showed significant declines throughout the 1980s until about 1992, when rates reached a low point.

- Data showed increasing rates of marijuana use during the early to mid-1990s, reaching a peak in the late 1990s (albeit a much lower peak that in the late 1970s).

- This peak in the late 1990s was followed by declines in use after the turn of the 21st century and an increase in the most recent years

Trends in Youth Perceptions of Risk

The extent to which young people believe that marijuana or other drugs might cause them harm is an important factor influencing their use of these substances. Lower levels of perceived risk are associated with higher use rates.

Surveys have found some troubling trends in recent years, with young Americans (ages 12 to 17), as the percentage reporting thinking there was a great risk of harm in smoking marijuana has decreased, as detailed in the chart below.

These data on marijuana use are of particular concern since trends in the perception of harm of smoking marijuana also have been declining over the same period of time. Prior research indicates that declines in these perceptions are predictive of increases in use.

Q. What are state laws pertaining to marijuana?

Follow this link for a more detailed overview of state laws.

Q. What is the difference between decriminalization, legalization, and medical marijuana?

There is significant public discussion around marijuana, much of which includes the terms legalization, decriminalization, and medical marijuana. Below are very general definitions for these terms:

Marijuana Legalization– Laws or policies which make the possession and use of marijuana legal under state law.

Marijuana Decriminalization– Laws or policies adopted in a number of state and local jurisdictions which reduce the penalties for possession and use of small amounts of marijuana from criminal sanctions to fines or civil penalties.

Medical Marijuana– State laws which allow an individual to defend him or herself against criminal charges of marijuana possession if the defendant can prove a medical need for marijuana under state law.

Q. Is the government putting people in prison for marijuana use?

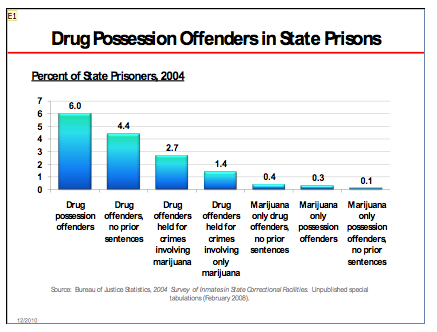

Simply stated, there are very few people in state or Federal prison for marijuana-related crimes. It is useful to look at all drug offenses for context. Among sentenced prisoners under state jurisdiction in 2008, 18% were sentenced for drug offenses. We know from the most recent survey of inmates in state prison that only six percent (6%) of prisoners were for drug possession offenders, and just over four percent (4.4%) were drug offenders with no prior sentences.

In total, one tenth of one percent (0.1 percent) of state prisoners were marijuana possession offenders with no prior sentences.

For Federal prisoners, who represent 13 percent of the total prison population, about half (51 percent) had a drug offense as the most serious offense in 2009. And Federal data show that the vast majority (99.8 percent) of Federal prisoners sentenced for drug offenses were incarcerated for drug trafficking.

Many advocates of marijuana legalization point to the significant number of marijuana-related arrests, including for the sale, manufacturing, and possession of the drug, as an unnecessary burden on criminal justice system. While Federal, state, and local laws pertaining to marijuana do lead to criminal justice costs, it is important to understand how decriminalization or legalization might further exacerbate these costs. Alcohol, a legal, carefully regulated substance, provides useful context for this discussion. Arrests for alcohol-related crimes, such as violations of liquor laws and driving under the influence, totaled nearly 2.5 million in 2010 — far more than arrests for all illegal drug use, and certainly far more than arrests for marijuana-related crimes. It is therefore fair to suggest that decriminalizing or legalizing marijuana might not reduce the drug’s burden to our justice and public health systems with respect to arrests, but might increase these costs by making the drug more readily available, leading to increase use, and ultimately to more arrests for violations of laws controlling its manufacture, sale, and use.

Q. Why is the Federal Government opposed to medical marijuana?

It is the Federal government’s position that marijuana be subjected to the same rigorous clinical trials and scientific scrutiny that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) applies to all other new medications, a comprehensive process designed to ensure the highest standards of safety and efficacy.

It is this rigorous FDA approval process, not popular vote, that should determine what is, and what is not medicine. The raw marijuana plant, which contains nearly 500 different chemical compounds, has not met the safety and efficacy standards of this process. According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), smoking marijuana is an unsafe delivery system that produces harmful effects.

The FDA has, however, recognized and approved the medicinal use of isolated components of the marijuana plant and related synthetic compounds. Dronabinol is one such synthetically produced compound, used in the FDA-approved medicine Marinol, which is already legally available for prescription by physicians whose patients suffer from nausea and vomiting related to cancer chemotherapy and wasting (severe weight loss) associated with AIDS. Another FDA-approved medicine, Cesamet, contains the active ingredient Nabilone, which has a chemical structure similar to THC, the active ingredient of marijuana. And Sativex, an oromucosal spray approved in Canada, the UK, and other parts of Europe for the treatment of multiple sclerosis spasticity and cancer pain, is currently in late-stage clinical trials with the FDA. It combines THC and another active ingredient in marijuana, cannabidiol (CBD), and provides therapeutic benefits without the “high” from the drug.

A number of States have passed voter referenda or legislative actions allowing marijuana to be made available for a variety of medical conditions upon a licensed prescriber’s recommendation, despite such measures’ inconsistency with the scientific thoroughness of the FDA approval process. But these state actions are not, and never should be, the primary test for declaring a substance a recognized medication. Physicians routinely prescribe medications with standardized modes of administration that have been shown to be safe and effective at treating the conditions that marijuana proponents claim are relieved by smoking marijuana. Biomedical research and medical judgment should continue to determine the safety and effectiveness of prescribed medications.

Q. Does the Federal government block medical marijuana research?

No. The Federal government supports studies that meet accepted scientific standards and successfully compete for research funding based on peer review and potential public health significance. The Federal Government will continue to call for research that may result in the development of products to effectively treat debilitating diseases and chronic pain. Already, there are DEA-registered researchers eligible to study marijuana, and currently there are Phase III clinical trials underway examining the medical utility of a spray containing a mixture of two active ingredients in marijuana (i.e., Sativex).

A number of government-funded research projects involving marijuana or its component compounds have been completed or are currently in progress. Studies include evaluation of abuse potential, physical/psychological effects, adverse effects, therapeutic potential, and detection. It is worth noting that a number of these studies include research with smoked marijuana on human subjects.

The Federal government is committed to the highest standards for basic science and clinical research on wide array of substances, including marijuana, that show promise.

Q. Wouldn’t legalizing marijuana remove a major source of funding for Mexican drug trafficking organizations?

No, violent Mexican criminal organizations derive revenue from more than just marijuana sales. They also produce and traffic methamphetamine and heroin, continue to move significant amounts of cocaine, and conduct an array of criminal activities including kidnapping, extortion, and human trafficking. Because of the variety and scope of the cartels’ business, and its illicit and purposefully obscured nature, determining the precise percentage of revenues from marijuana is problematic, but we can be confident that even the complete elimination of one of their illicit “product lines” will not result in disbanding of their criminal organizations.

The existing black market for marijuana will not simply disappear if the drug is legalized and taxed. Researchers from the RAND Corporation have noted a significant profit motive for existing black market providers to stay in the market, as “as they can still cover their costs of production and make a nice profit.”

With this in mind, it is crucial to reduce demand for marijuana in the United States and work with the Government and people of Mexico to continue our shared commitment to defeat violent drug cartels.

Q: Couldn’t legalizing and taxing marijuana generate significant revenue?

A: While taxing marijuana could generate some revenues for state and local governments, research suggests that the economic costs associated with use of the drug could far outweigh any benefit gained from an increase in tax revenue.

In the United States in 2007, illegal drugs cost $193 billion ($209 billion in 2011 dollars) in health care, lost productivity, crime, and other expenditures. Optimistic evaluations of the potential financial savings from legalization and taxation are often flawed, and fail to account for the considerable economic and social costs of drug use and its consequences.

This issue is particularly relevant in the marijuana debate. For example, the California Board of Equalization estimated that $1.4 billion of potential revenue could arise from legalization. This assessment, according to the RAND Corporation is “based on a series of assumptions that are in some instances subject to tremendous uncertainty and in other cases not valid.”

Another recent report from RAND examines this issue in greater detail. The report concludes that legalization and taxation of marijuana would lead to a decrease in the retail price of the drug, likely by more than 80 percent. While this conclusion is subject to a number of uncertainties, including the effect of legalization on production costs and price and the Federal government’s response to the state’s legalization of a substance that would remain illegal under Federal law, it is fair to say that the price of marijuana would drop significantly. And because drug use is sensitive to price, especially among young people, higher prices help keep use rates relatively low.

The existing black market for marijuana will not simply disappear if the drug is legalized and taxed. RAND also noted that “there is a tremendous profit motive for the existing black market providers to stay in the market, as they can still cover their costs of production and make a nice profit.” Legalizing marijuana would also place a dual burden on the government of regulating a new legal market while continuing to pay for the negative side effects associated with an underground market, whose providers have little economic incentive to disappear.

Legalization means price comes down; the number of users goes up; the underground market adapts; and the revenue gained through a regulated market most likely will not keep pace with the financial and social cost of making this drug more accessible.

Consider the economic realities of other substances. The tax revenue collected from alcohol pales in comparison to the costs associated with it. Federal excise taxes collected on alcohol in 2009 totaled around $9.4 billion; state and local revenues from alcohol taxes totaled approximately $5.9 billion. Taken together ($15.3 billion), this is just over six percent of the nearly $237.8 billion adjusted for 2009 inflation) in alcohol-related costs from health care, treatment services, lost productivity, and criminal justice.

While many levels of government and communities across the country are facing serious budget challenges, we must find innovative solutions to get us on a path to financial stability – it is clear that the social costs of legalizing marijuana would outweigh any possible tax that could be levied.

Q. What impact does marijuana cultivation have on the environment?

Outdoor marijuana cultivation creates a host of negative environmental effects. These grow sites affect wildlife, vegetation, water, soil, and other natural resources through the use of chemicals, fertilizers, terracing, and poaching. Marijuana cultivation results in the chemical contamination and alteration of watersheds; diversion of natural water courses; elimination of native vegetation; wildfire hazards; poaching of wildlife; and disposal of garbage, non-biodegradable materials, and human waste.

Marijuana growers apply insecticides directly to plants to protect them from insect damage. Chemical repellants and poisons are applied at the base of the marijuana plants and around the perimeter of the grow site to ward off or kill rats, deer, and other animals that could cause crop damage. Toxic chemicals are applied to irrigation hoses to prevent damage by rodents. According to the National Park Service, “degradation to the landscape includes tree and vegetation clearing, use of various chemicals and fertilizers that pollute the land and contribute to food chain contamination, and construction of ditches and crude dams to divert streams and other water sources with irrigation equipment.”

Outdoor marijuana grow site workers can also create serious wildfire hazards by clearing land for planting (which results in piles of dried vegetation) and by using campfires for cooking, heat, and sterilizing water. In August 2009, growers destroyed more than 89,000 acres in the Los Padres National Forest in Southern California. The massive La Brea wildfire began in the Los Padres National Forest within the San Rafael Wilderness area in Santa Barbara County, California, and subsequently spread to surrounding county and private lands. According to United States Forest Service (USFS) reporting, the source of the fire was an illegal cooking fire at an extensive, recurring Drug Trafficking Organization-operated outdoor grow site where more than 20,000 marijuana plants were under cultivation. According to the USFS, suppression and resource damage costs of the La Brea wildfire totaled nearly $35 million.

In addition to the environmental damage, the cost to rehabilitate the land damaged by illicit marijuana grows is prohibitive, creating an additional burden to public and tribal land agency budgets. According to internal Park Service estimates, full cleanup and restoration costs range from $14,900 to $17,700 per acre.* Total costs include removal and disposal of hazardous waste (pesticides, fuels, fertilizers, batteries) and removal of camp facilities, irrigation hoses, and garbage. Full restoration includes re-contouring plant terraces, large tent pads, and cisterns/wells and re-vegetating clear-cut landscapes.

The United States has an abundance of public lands set aside by Congress for conservation, recreational use, and enjoyment of the citizens of this country and visitors from around the globe. Unfortunately, criminal organizations are exploiting some of these public and tribal lands as grow sites for marijuana.

During calendar year 2010, nearly 10 million plants were removed from nearly 24,000 illegal outdoor grow sites nationwide. These numbers provide insight into the size and scale of the negative environmental impact that marijuana cultivation can have on our Nation’s public lands.

*Source: Marijuana Site Reclamation and Restoration Cost Analysis.” U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Service. December 9, 2010(unpublished data).