2011 National Drug Control Strategy - Introduction

Introduction

In May of 2010, President Obama released the Administration’s inaugural National Drug Control Strategy. Based on the premise that drug use and its consequences pose a threat not just to public safety, but also to public health, the 2010 Strategy represented the first comprehensive rebalancing of Federal drug control policy in the nearly 40 years since President Nixon declared illicit drugs “public enemy number one.”

This 2010 Strategy continues to serve as the Administration’s blueprint to reduce drug use and its associated consequences in the United States. It describes specific actions that Federal departments and agencies are taking to achieve the Administration’s two main drug control goals: curtailing illicit drug consumption in America and reducing the consequences of drug abuse that threaten our public health and safety. It also highlights the development and implementation of evidence-based prevention and intervention practices and policies supported by Federal partnerships with state, local, and tribal jurisdictions and other stakeholders.

The actions enumerated in the 2011 Strategy will build on the 2010 Strategy and on several major drug policy milestones achieved over the last year. On August 3, 2010, President Obama signed into law the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, a significant and long-overdue piece of criminal justice reform, which reduces the disparity in the amounts of powder cocaine and crack cocaine required for the imposition of mandatory minimum sentences. This act eliminates the mandatory minimum sentence for simple possession of crack cocaine in Federal cases. It also increases penalties for major drug traffickers. On October 12, 2010, the President signed into law the Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010, which will help communities combat the Nation’s prescription drug abuse epidemic by providing states and localities the authority to collect unused prescription drugs for safe disposal. Both of these legislative accomplishments are the result of support from both Democrats and Republicans, illustrating how combating drug use and its consequences continues to be a bipartisan effort. As Americans work together to address our Nation’s shared challenges, the health, well-being, and safety of our citizens continue to serve as the basis for strengthening our economy and our country overall. A healthy, productive, and drug-free workforce fosters competition and innovation within our neighborhoods, towns, and communities. Addressing our Nation’s drug problem will also ensure that our fellow citizens can contribute to our shared successes and America’s future generations will continue to lead the world in innovation and ingenuity.

Framing the Problem

The Obama Administration’s approach to the drug problem is borne out of the recognition that drug use is a major public health threat, and that drug addiction is a preventable and treatable disease. Whether struggling with an addiction, worrying about a loved one’s substance abuse, or being a victim of drugrelated crime, millions of people in this country live with the devastating consequences of illicit drug use. Overall, the economic impact of illicit drug use on American society totaled more than $193 billion in 2007, the most recent year for which data are available. Drug-induced deaths now outnumber gunshot deaths in America, and in 17 states and Washington, D.C., they now exceed motor vehicle crashes as the leading cause of injury death. In addition, 1 in every 10 cases of HIV diagnosed in 2007 was transmitted via injection drug use, and drug use itself fosters risky behavior contributing to the spread of infectious diseases nationwide. Furthermore, studies of children in foster care find that two-thirds to three-quarters of cases involve parental substance abuse. Also, low-achieving high school students are more likely to use marijuana and other substances than high-achieving students. Finally, Americans with drug or alcohol use disorders spend more days in the hospital and require more expensive care than they would absent such disorders. This contributes to almost $32 billion in medical costs per year—a burden that our communities, employers, and small businesses cannot afford to bear.

Source: CDC, WONDER online databases [http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd 10.html] (August 19, 2010). Despite significant gains over the past decade, recent survey results have shown troubling increases in drug use in America. Young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 have the highest rates of current drug use at nearly 20 percent. Each day, an estimated 4,000 young people between the ages of 12 and 17 use drugs for the first time. Additionally, more high school seniors now use marijuana than tobacco, and non-medical use of prescription or over-the-counter drugs remains unacceptably high, accounting for 6 of the top 10 substances used by 12th graders in the year prior to the survey. While these results inspire a call to action, they are not unexpected. Data from the last 2 years show young people’s attitudes towards drugs are weakening, particularly toward marijuana and prescription drugs. When youth attitudes weaken, increases in use are never far behind.

The 2011 Strategy continues efforts to coordinate an unprecedented government-wide public health approach to reduce drug use and its negative consequences in the United States while maintaining strong support for law enforcement. Experience shows we can continue to make progress in reducing drug use by supporting balanced and evidence-based drug control strategies. Data show that, despite recent increases in drug use, the percentage of Americans using illicit drugs is half the rate it was 30 years ago, cocaine production in Colombia has dropped by almost two-thirds since 2001, and increasing numbers of non-violent offenders are being diverted into treatment instead of jail. Previous national efforts to reduce smoking, drunk driving, and other public health threats have shown that sustained and balanced approaches can work to significantly improve public health and safety. The Administration’s National Drug Control Strategy provides a roadmap to build on these past successes.

Policy Priorities

In addition to the overarching drug policy outlined above, we are focused on three areas where substantial short-term progress can make a significant difference in people’s lives—prescription drug abuse, drugged driving, and prevention.

Reducing Prescription Drug Abuse (Also discussed in Chapters 1, 5, 6, and 7) Prescription drug abuse is the Nation’s fastest-growing drug problem. While prescription drugs have important benefits when used properly, they are also increasingly abused by teens and young adults. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more than 27,000 people died from drug overdose deaths in 2007. These deaths primarily involve prescription drug pain relievers. The rate of overdose deaths from such drugs has risen five-fold since 1990 and has never been higher. Prescription drugs are now involved in more overdose deaths than heroin and cocaine combined. Because prescription drugs are legal, they are easily accessible and are most frequently acquired through friends and family members. Further, some individuals who misuse prescription drugs, particularly teens, mistakenly believe these substances are safer than illicit drugs because they are prescribed by healthcare professionals and legally sold by pharmacies.

Although we must carefully balance the need to minimize abuse of pharmaceuticals with the need to maximize safe and legitimate access to these products, the Administration has made reducing prescription drug abuse a national priority. This Strategy, along with the Administration’s recently released plan (titled, Epidemic: Responding to America’s Prescription Drug Abuse Crisis) provides a blueprint for reducing prescription drug abuse by supporting the expansion of prescription drug monitoring programs, encouraging community prescription take-back initiatives, recommending disposal methods to remove unused medications from the home, supporting education for patients and healthcare providers, and reducing the prevalence of illegal prescribing practices and doctor shopping through enforcement efforts. The complete plan can be found here:

http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/prescriptiondrugs/

Addressing Drugged Driving (Also discussed in Chapters 1 and 5)

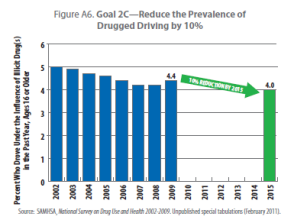

Similar to the highly successful efforts to prevent drunk driving, drugged driving demands a national response. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), roughly one in eight weekend, nighttime drivers tested positive for illicit drugs. In 2009, drivers who were killed in motor vehicle crashes (and subsequently tested and had results reported), one in three tested positive for drugs. One in eight high school seniors self-reported that in the last 2 weeks they drove a car after using marijuana. To help shed light on this threat, the President declared December 2010 National Impaired Driving Prevention Month and called on all Americans to recommit to preventing the loss of life by practicing safe driving practices and reminding others to be sober, drug free, and safe on the road. In follow-up to the activities called for in this Strategy, drugged driving will be addressed domestically by raising public awareness in partnership with national non-governmental organizations, local law enforcement, and courts; providing technical assistance to states considering per se laws; developing an online version of NHTSA’s Advanced Roadside Impaired Driving Enforcement Program; and improving testing methods for impaired drivers.

Preventing Drug Use Before it Begins (Also discussed in Chapter 1)

Scientific evidence makes clear that drug prevention is the most cost-effective, common-sense approach to promoting safe and healthy communities. Youth who refrain from drug use have better academic performance. Communities enjoy reduced drugged driving and, therefore, safer roads. Employers experience lower absenteeism, resulting in more productive workplaces. Drug use prevention efforts also impact HIV transmission rates by decreasing injection drug use, creating safer home environments by reducing the number of drug-endangered children, and revitalizing neighborhoods through coalition-based efforts.

Americans from every walk of life suffer from drug addiction, especially with the increasing abuse of prescription drugs. The next generation deserves every opportunity to succeed in life, and effective prevention gives them much better odds.

Special Populations

While drug addiction respects no geographic, ethnic, economic, or social boundaries, there are some specific populations with unique challenges and needs in addressing their substance abuse issues. Throughout this Strategy, the Administration is proposing new policies and practices that will improve the way the Federal government responds to the special populations described below.

College and University Students

About 40 percent of college students report binge drinking (defined for men as five or more drinks in a row on at least one occasion in the past 2 weeks and for women as four or more drinks). Other drug use, including marijuana and prescription drug abuse, is also of concern. One study at a large university reported that 34 percent of students had used a prescription stimulant medication during times of academic stress, believing that these drugs increased reading comprehension, cognition, and memory. Substance use by college students also contributes to numerous academic, social, and health-related problems. In one national study of 14,000 college students, 29.5 percent reported missing a class because of alcohol use and almost 22 percent who drank in the year prior reported falling behind in their work. In another national study examining the consequences of binge drinking among college students 10 years post-college, binge and frequent drinking was associated with academic attrition, early departure

from college, and lower earnings in post-college employment.

Women and Families

Seeking treatment for drug addiction poses hurdles specific to women because many treatment programs are designed for and used mostly by men and many women must weigh competing family concerns against the need for substance abuse treatment. Because many traditional treatment programs do not allow for the inclusion of children, a woman may be torn between the need to provide child care and the need for treatment. Involvement with the child welfare system also complicates a woman’s decision to seek care, because admitting to a substance abuse problem may lead to involvement with the criminal justice system and the loss of custody of children. Girls have caught up to boys in their initiation of the use of illicit drugs and alcohol. Teenage girls’ drug use is frequently tied to self-esteem issues, depression, and peer pressure, but often prevention and treatment programming do not address these risk factors.

Military, Veterans, and Their Families

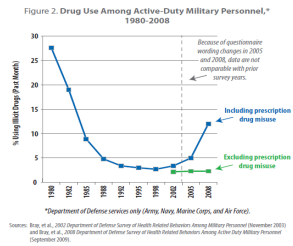

Far too many brave men and women who have risked their lives in service to our country are now suffering from physical, mental health, and substance abuse problems. A 2008 Department of Defense (DOD) survey revealed that 11.9 percent of active duty military personnel reported current illicit drug use, including non-medical use of prescription drugs. Largely due to regular testing, the use of illicit drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine is rare among active duty military. The percentage reporting prescription drug misuse (11.5%) is more than double that of the civilian population in the age group 18-64 (4.4%).

In response to the increased concern about misuse of prescription medications, DOD has established a Pharmacovigilance Center. By taking advantage of technological advances, DOD is able to monitor possible medication misuse and assess the effectiveness of policies, formulary decisions, risk reduction measures, and point of care initiatives within the DOD system. However, diversion, drug sharing, and prescriptions obtained outside the DOD system, which may have contributed to the increase in prescription misuse in recent years, are not captured through the Pharmacovigilance Center. DOD will partner with the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) to further enhance their ability to identify misuse by exploring data sharing with state prescription drug monitoring programs.

Additionally, the most recent survey data from the Justice Department found that an estimated 60 percent of the 140,000 Veterans in Federal and state prisons were struggling with a substance use disorder, while approximately 25 percent of veterans in state prison reported using drugs at the time of the offense. The Veterans Health (VHA) has made three special populations the target of particular VA substance use disorder prevention and treatment efforts: service members who have returned from Iraq and Afghanistan and are eligible for VHA sevices; patients receiving care in Metal

Health Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Programs; and patients suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Enhancing the psychological and behavioral health of military families was the first identified priority in the Presidential report, Strengthening our Military Families, which is designed to provide a comprehensive strategy to improve and expand substance abuse prevention, treatment, and recovery services available for active duty Armed Forces, the National Guard, and the Reserves.

Goals and Baselines

The 2010 Strategy called for a balanced approach of prevention, treatment, law enforcement, interdiction, and international partnerships to achieve a 15-percent reduction in the rate of youth drug use over 5 years, as well as similar reductions in chronic drug use and drug-related consequences such as drug-induced deaths and drugged driving.

Within its seven chapters, last year’s Strategy articulated seven objectives that support the overall goals and presented 106 specific action items whose implementation is necessary to achieve the Strategy’s goals and the Administration’s vision of a balanced approach to drug policy in the United States. The Strategy provided both a brief description of the action items and, for each item, a list of the agencies responsible for their implementation. Following the release of the Strategy, ONDCP, working with interagency partners, developed a process to track and ensure successful implementation of the 106 action items and designed a Performance Reporting System (PRS) for gauging the overall effectiveness of the Strategy.

The 2011 Strategy reports progress toward achievement of the many action items enumerated in the 2010 Strategy for which there are specific accomplishments to document. The full list of Action Items can be found at http://whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/strategy. Action Items addressed in this Strategy are marked throughout the document.

Appendix One contains tables and short narrative descriptions for the Strategy’s two main goals and their seven sub-measures. For all the goals and sub-measures, 2009 data are used as the baseline, although in some cases, 2009 data are not yet available. The PRS will track progress and report annually on the Strategy’s seven strategic objectives. In addition, a report on the design of the PRS will be released under separate cover.

The 2011 Strategy is a recommitment to the goals, objectives, and activities in the Administration’s inaugural Strategy, which set forth the foundation and direction of President Obama’s drug policy. This Strategy will continue to ensure continuity, accountability, and transparency in the Administration’s

efforts to reduce drug use and its consequences.

The 2010 National Drug Control Strategy provided a roadmap for how to achieve ambitious 5-year goals of reducing drug use and its consequences. Since the publication of the Strategy, National Drug Control agencies have worked diligently to accomplish these goals, their progress has been tracked through a multi-agency reporting mechanism, and many of their accomplishments are detailed in this document.

Successful counterdrug efforts rely not just on the efforts of Federal drug control agencies, but on cooperation between the state, tribal, and local entities that work every day to reduce drug use and its consequences. This Strategy highlights some of the non-Federal programs that demonstrated outstanding success or a unique approach to the problems facing their communities. To truly accomplish our goals, state, local, and tribal governments must also implement smart policies.

Healthy and drug-free communities strengthen the country by creating a workforce ready to respond to the needs of a changing global economy, assuring the safety of our schools and streets, and creating healthy families and communities. This is how we win the future. In the coming year, the Administration will continue to work with partners, both Federal and non-Federal, to accomplish our goals. An update to this document will be published next year at this time.

In this document, I have put forward programs and policies that make good use of Federal resources in order to save lives while saving states, communities, and businesses money. Prevention must occur in every setting and be embedded into the fabric of our communities. Treatment and recovery are real and effective. The disease of addiction is unfortunately often obscured by denial. Unlike most diseases, the afflicted often do not seek assistance for their illness. Therefore, treatment must sometimes be coupled with encouragement and sometimes with consequences—thus in non-traditional settings, such as the criminal justice system.

Since the start of this Administration everywhere I’ve traveled and in every meeting I’ve attended, I’ve received helpful feedback from people who work daily in drug control, whether in prevention, treatment, law enforcement, or diplomacy. My staff and I will continue tirelessly to identify the strengths and weaknesses of our current efforts and study novel approaches for wider implementation.

National Drug Control Strategy Goals to be Attained by 2015

Goal 1: Curtail illicit drug consumption in America

• 1a. Decrease the 30-day prevalence of drug use among 12– to 17- year- olds by 15%

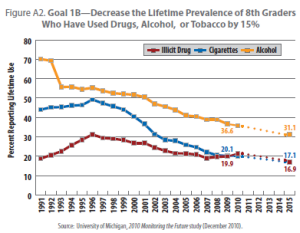

• 1b. Decrease the lifetime prevalence of 8th graders who have used drugs, alcohol, or tobacco by 15%

• 1c. Decrease the 30-day prevalence of drug use among young adults aged 18–25 by 10%

• 1d. Reduce the number of chronic drug users by 15%

Goal 2: Improve the public health and public safety of the American people by reducing the consequences

of drug abuse

• 2a. Reduce drug-induced deaths by 15%

• 2b. Reduce drug-related morbidity by 15%

• 2c. Reduce the prevalence of drugged driving by 10%

Data Sources: SAMHSA’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health (1a, 1c); Monitoring the Future (1b); What Americans

Spend on Illegal Drugs (1d); and Prevention (CDC) National Vital Statistics System (2a); SAMHSA’s Drug Abuse Warning

Network drug-related emergency room visits, and CDC data on HIV infections attributable to drug use (2b); National

Survey on Drug Use and Health and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) roadside survey (2c)

National Drug Control Strategy Goals to be Attained by 2015

Goal 1: Curtail illicit drug consumption in America

• 1a. Decrease the 30-day prevalence of drug use among 12– to 17- year- olds by 15%

• 1b. Decrease the lifetime prevalence of 8th graders who have used drugs, alcohol, or tobacco by 15%

• 1c. Decrease the 30-day prevalence of drug use among young adults aged 18–25 by 10%

• 1d. Reduce the number of chronic drug users by 15%

Goal 2: Improve the public health and public safety of the American people by reducing the consequences

of drug abuse

• 2a. Reduce drug-induced deaths by 15%

• 2b. Reduce drug-related morbidity by 15%

• 2c. Reduce the prevalence of drugged driving by 10%

Data Sources: SAMHSA’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health (1a, 1c); Monitoring the Future (1b); What Americans

Spend on Illegal Drugs (1d); and Prevention (CDC) National Vital Statistics System (2a); SAMHSA’s Drug Abuse Warning

Network drug-related emergency room visits, and CDC data on HIV infections attributable to drug use (2b); National

Survey on Drug Use and Health and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) roadside survey (2c) Figure A1. Goal 1A—Decrease the 30˜Day Prevalence of

Drug Use Among Youth by 15%

Bar chart shows Goal 1A—Decrease the 30˜Day Prevalence of

Drug Use Among Youth by 15%

Source: SAMHSA, 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (September 2010).

List of Acronyms

ACYF Administration for Children, Youth, and Families [HHS]

ADAM Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring program

AFP Australian Federal Police

ARIDE Advanced Roadside Impaired Driving Enforcement

ARQ United Nations Annual Reports Questionnaire

ATF Bureau for Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives [DOJ]

ATI Above the Influence [ONDCP]

ATR Access to Recovery

AVIPA Afghanistan Vouchers for Increased Production in Agriculture

BEST Border Enforcement Security Team

BJA Bureau of Justice Assistance [DOJ]

BJS Bureau of Justice Statistics [DOJ]

BOP Bureau of Prisons [DOJ]

CADCA Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America

CARSI Central American Regional Security Initiative

CBP Customs and Border Protection [DHS]

CBSI Caribbean Basin Security Initiative

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [HHS]

CHC Community Health Center

CICAD Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission

CMEA Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2006

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [HHS]

CND Commission on Narcotic Drugs

DAWN Drug Abuse Warning Network

DEA Drug Enforcement Administration [DOJ]

DEC Drug Endangered Children

DFC Drug Free Communities program [ONDCP]

DHE Domestic Highway Enforcement

DHS U.S. Department of Homeland Security

DMI Drug Market Interventions

DOD U.S. Department of Defense

DOJ U.S. Department of Justice

DOT U.S. Department of Transportation

DTO Drug Trafficking Organization

Education U.S. Department of Education

EHR Electronic Health Record

EOP Executive Office of the President

EPIC El Paso Intelligence Center

EU European Union

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigations [DOJ]

FDA Food and Drug Administration [HHS]

FDSS Federal Drug Seizure System

FinCEN Financial Crimes Enforcement Network [Treasury]

FIT Financial Investigation Teams [DEA]

FQHC Federally Qualified Health Center

FSKN Russian Federal Drug Control Service

GangTECC Gang Targeting, Enforcement, and Coordination Center [DOJ]

GBHI Grants for the Benefit of Homeless Individuals [HHS]

GROW Guiding the Recovery of Women

HHS U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

HIDTA High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area [ONDCP]

HIT Health Information Technology

HOPE Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement

HRPDMP Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program

HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration [HHS]

HUD U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

IBET Integrated Border Enforcement Team

ICANN Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers

ICE Immigration and Customs Enforcement [HHS]

ICSCU Indian Country Special Crimes Unit

IED Improvised Explosive Device

IDU Injection Drug User

IHS Indian Health Service [HHS]

IISC Intelligence and Investigative Support Center

IOM Institute of Medicine

IRS Internal Revenue Service [Treasury]

JIATF-South Joint Interagency Task Force South

JMATE Joint Meeting on Adolescent Treatment Effectiveness

MASBIRT Massachusetts Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

MCN Afghan Ministry of Counter Narcotics

MDMA Ecstasy

Media

Campaign National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign [ONDCP]

MTF Monitoring the Future study

NASPER National All Schedules Prescription Electronic Reporting program

NCSACW National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare [HHS]

NHTSA National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [DOT]

NIC National Institute of Corrections [DOJ]

NIDA National Institute on Drug Abuse [HHS]

NIJ National Institute of Justice [DOJ]

NMPI National Methamphetamine and Pharmaceutical Initiative

NSDUH National Survey on Drug Use and Health

NSS National Seizure System

NY/NJ New York/New Jersey High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area

OAS Organization of American States

OCDETF Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force [DOJ]

OJJDP Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention [DOJ]

OJP Office of Justice Programs [DOJ]

ONDCP Office of National Drug Control Policy

PACT360 Police and Communities Together

PDMP Prescription Drug Monitoring Program

PEPFAR President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

PPC Prevention Prepared Communities

PRS Performance Reporting System

PTSD Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

ROSC Recovery-Oriented Systems of Care

RSAT Residential Substance Abuse Treatment

RSS Recovery Support Services

RTC The Next Door Residential Transition Center

SADD Students Against Destructive Decisions

SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [HHS]

SASPG Substance Abuse State Prevention Grant

SBIRT Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

SOD Special Operations Division

SPF-SIG Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grants

STABO Short Term Airborne Operations

State U.S. Department of State

STRIDE System to Retrieve Information from Drug Evidence

TASC Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities

TCE Targeted Capacity Expansion

THC Tetrahydrocannabinol, the active ingredient in marijuana

TIC The Interdiction Committee

Treasury U.S. Department of the Treasury

TRICARE Healthcare program serving current and former military and their families

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development [State]

USMLE U.S. Medical Licensing Examination

USPS United States Postal Service

VA U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

VHA Veterans Health Administration [VA]

YRBS Youth Risk Behavior Survey

1. United States Department of Justice. (2011). The Economic Impact of Illicit Drug Use on American Society. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gov/ndic.

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Special tabulations from CDC’s Wonder database on vital statistics. Retrieved from http://wonder.cdc.gov.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2007., Vol. 19. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2007report.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Alcohol and Other Drug Use and Academic Achievement. Retrieved from

http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/health_and_academics/pdf/alcohol_other_drug.pdf.

5. National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare. Retrieved from

http://www.ncsacw.samhsa.gov/files/Research_Studies_Prevalence_Factsheets.pdf. While figures vary for methodological reasons, most studies find that for one-third to two-thirds of children involved with the child welfare system, parental substance abuse is a contributing factor. The lower figures tend to involve child abuse reports and the higher ones most often refer to children in out-of-home care. Sources: U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services. (1999). Blending perspectives and building common ground: A report to congress on substance abuse and child protection. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; and Semidei, J., Radel, L. F., & Nolan, C. (2001). Substance abuse and child welfare: Clear linkages and promising responses. Child Welfare. 80(2),109-28; and Young, N. K., Boles, S. M., & Otero, C. (2007). Parental substance use disorders and child maltreatment: Overlap, gaps, and opportunities. Child Maltreatment, 12(2), 137-149.

6. Harwood, H. (2000). Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: Estimates, update, and data. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism., Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2001). The economic costs of drug abuse in the United States, 1992-1998.Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President.

7. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2009). Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434). Rockville, MD.

8. Johnston, L.D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2011). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

9. Johnston, L.D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2011). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Unintentional drug poisoning in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Poisoning/brief.htm.

11. Lacey, J. H., Kelley-Baker, T., Furr-Holden, D., Voas, R. B., Romano, E., Ramirez, A., …Berning, A. (2009). 2007 National roadside survey of alcohol and drug use by drivers: Drug results. (DOT HS 811 249). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

12. National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2010). Traffic safety facts: Drug involvement of fatally injured drivers. (DOT HS 811 415). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

13. National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2010). Traffic safety facts: Drug involvement of fatally injured drivers. (DOT HS 811 415). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Alcohol and other drug use and academic achievement: 2009 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/health_and_academics/pdf/alcohol_other_drug.pdf.

15. Griffin, A. G., Ramchand, R., Edelen, M. O., McCaffrey, D. F., & Morral, A. R. (2011). Associations between abstinence in adolescence and economic and educational outcomes seven years later among high-risk youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 113, 118-124.

16. U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2011). Countermeasures that work: A highway safety countermeasure guide for state highway safety offices. (6th ed.).(HS 811 44). Washington, DC: Department of Transportation Publication.

17. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

18. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2003). Preventing drug abuse among children and adolescents: research-based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders. (2nd ed.). (NIH Publication No. 04-4212 (A). Bethesda, MD.

19. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (2006). Research report series: HIV/AIDS. (NIH Publications No. 06-5760). Bethesda, MD.

20. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional,,and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

21. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

22. DeSantis, A. D., Webb, E. M., & Noar, S. M. (2008). Illicit use of prescription ADHD medications on a college campus: A multimethodological approach. Journal of American College Health, 57(3), 315-323.

23. Wechsler, H., Eun Lee, J., Kuo, M., Seibring, M., Nelson, T. B., & Lee, H. (2002). Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from Harvard School of Public Health College alcohol surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health, 50, 203–217.

24. Jennison, K. M. (2004). The short effects and unintended long consequences of binge drinking in college: A 10- year follow study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 30(3), 659-684.

25. Substance Abuse and Menthal Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and health: Summary of national findings. (Vol 1). (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

26. National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. (2003). The formative years: Pathways to substance abuse among girls and young women ages 8–22. Retrieved from

http://www.casacolumbia.org/articlefiles/380-Formative_Years_Pathways_to_Substance_Abuse.pdf.

27. Department of Defense. (2009). 2008 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behavior Among Active Duty Military Personnel. Retrieved from http://www.tricare.mil/2008HealthBehaviors.pdf.

28. U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2007). Veterans in state and federal prison 2004. (NCJ 217199). Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/vsfp04.pdf.

29. Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2011). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

30. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2003). Preventing drug use among children and adolescents: A research-based guide for parents, educators, and communities. (2nd ed.). (NIH Publication No. 04-4212 (A)). Bethesda, MD.

31. Centers for Disease Control. (2009). Alcohol and other drug use and academic achievement: 2009 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/health_and_academics/pdf/alcohol_other_drug.pdf.

32. Sullivan, M., & Risler, E. (2002). Understanding college alcohol abuse and academic performance: Selecting appropriate intervention strategies. Journal of College Counseling, 5 (2), 114-124.

33. National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2006). NIDA: Community drug alert bulletin - stress & substance abuse. Retrieved from http://archives.drugabuse.gov/stressalert/StressAlert.html#Anchor-PTSD-27350.

34. B. Fallik, Senior Public Health Analyst, Division of Systems Development, CSAP/SAMHSA/DHHS, personal communication, 2011.

35. Frosch, D. L.,Grande, D., Tarn, D. M., & Kravitz, R. L. (2010). A decade of controversy: Balancing policy with evidence in the regulation of prescription drug advertising. American Journal of Public Health,100(1), 24-32.

36. Greene, J. A., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2010). Pharmaceutical marketing and the new social media. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(22), 2087-2089.

37. Participating communities include: Phoenix, AZ; Tucson, AZ; Fresno, CA; Denver, CO; Hartford, CT; Tampa, FL; Douglasville, GA; Savannah, GA; Indianapolis, IN; Beaumont, TX; Houston, TX; Paducah, KY; Boston, MA; Minneapolis, MN; Billings, MT; Fargo, ND; Binghamton, NY; The Bronx, NY; Tulsa, OK; Youngstown, OH; Portland, OR; Philadelphia, PA; Providence, RI; Spokane, WA; Milwaukee, WI; Washington, DC.

38. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1). (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

39. National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2010). A snapshot of annual high-risk college drinking consequences. Retrieved from http://www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/StatsSummaries/snapshot.aspx.

40. Martinez, J. A., Sher, K. J., & Wood, P. K. (2008). Is heavy drinking really associated with attrition from college? The alcohol-attrition paradox. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(3), 450-456.

41. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2008). Drug-free workplace: A kit. Retrieved from http://www.workplace.samhsa.gov/wpworkit/index.html.

42. National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2010). Traffic safety facts: Drug involvement of fatally injured drivers. (DOT HS 811 415). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

43. National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2009). Results of the 2007 National Roadside Survey of Alcohol and Drug Use by Drivers.(DOT HS 811 175). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

44. Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2010, December 14). Teen marijuana use tilts up while some drugs decline in use. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan News Service.

45. Johnston, L.D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2011). Monitoring the Future: A synopsis of the 2009 results on teen use of illicit drugs and alcohol. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

46. Anthony, J. C., Warner, L. A., & Kessler, R. C. (1994). Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 2, 244-68.

47. Anthony, J.C. (2001). Cannabis dependence: Its nature, consequences and treatment. In R. A. Roffman & R. S. Stephens (Eds). The epidemiology of cannabis dependence (58-105). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

48. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2010). The DAWN report: Highlights of the 2009 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits. Retrieved from

http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k10/DAWN034/EDHighlightsHTML.pdf.

49. RAND Drug Policy Research Center. (2010). Altered States? Assessing how marijuana legalization in California could influence marijuana consumption and public budgets. Santa Monica, CA: Kilmer, B. et al.

50. RAND Drug Policy Research Center.(2010). Reducing drug trafficking revenues and violence in Mexico: would legalizing marijuana in California Help? Santa Monica, CA: Kilmer, B. et al.

51. Center for Science in the Public Interest. (2008). Federal alcohol excise tax basics. Retrieved from http://www.cspinet.org/booze/taxguide/excisetaxbasics.pdf.

52. Tax Policy Center. (2010). Alcohol tax revenue. Retrieved from

http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=399.

53. Harwood, H. (2000). Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: Estimates, update, and data. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2001). The economic costs of drug abuse in the United States, 1992-1998.Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President.

54. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Tobacco control state highlights 2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/state_data/state_highlights/2010/ Control State highlights 2010.

55. Xu, J., Kochanek, K., Murphy, S., & Tejada-Vera, B. (2010). Deaths: Final data for 2007. (National vital statistics reports, 58(19)). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

56. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Unintentional drug poisoning in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/poisoning/brief.htm.

57. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2008). Uniform crime reports. Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/ucr.htm.

58. Jaffe, S. L., & Compton, M. T. (1997). Marijuana update for child and adolescent psychiatrists. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry News, 2, 7-9.

59. Estee, S., Wickizer, T., He, L., Shah, M. F., & Mancuso, D. (2010). Evaluation of the Washington state screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment project: Cost outcomes for Medicaid patients screened in hospital emergency departments. Medical Care, 48(1), 18–24.

60. Mancuso, D., & Felver, B. E. (2010). Bending the health care cost curve by expanding alcohol/drug treatment. (Report 4.81). Olympia, WA: State Dept of Health And Social Services.

61. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

62. Martens, M. P., Cimini, M. D., Barr, A. R., Rivero, E. M., Vellis, P. A., Desemone, G. A., & Horner, K. J. (2007). Implementing a Screening and Brief Intervention for high-risk drinking in university-based health and mental health care settings: Reductions in alcohol use and correlates of success. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 2563-2572. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.005.

63. Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System, US Department of Health and Human Services, April 2010. “Reason for Removal” is a multiple response category; children may be represented in more than one category.

64. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

65. STATE HIE TOOLKIT-Online-Module: For purposes of this module, the term “vulnerable populations” will focus on the needs of persons, served by post-acute care (PAC), long term care, (LTC) and behavioral health (BH) providers, having: long-term physical, cognitive and functional disabilities; short-term rehabilitation needs; other medically complex and/or chronic illnesses; serious mental illness and/or substance abuse disorders, and/or; developmental disabilities; Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS, 2010.

66. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

67. Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2011). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

68. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

69. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. (July 15, 2010). The TEDS Report:Substance abuse treatment admissions involving abuse of pain relievers: 1998 and 2008. Rockville, MD.

70. Warner, M., Chen, L. H., & Makuc, D. M. (2009). Increase in fatal poisonings involving opioid analgesics in the United States, 1999–2006. (NCHS data brief, no 22). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

71. U.S. General Accounting Office. (May 2002). GAO Report to the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, Committee on Energy and Commerce, House of Representatives. Prescription drugs: State monitoring programs provide useful tool to reduce diversion. Retrieved from www.gao.gov/new.items/d02634.pdf.

72. Baehren, D. F., Marco, C. A.,Droz, D. E., Sinha, S., Callan, E. M., & Akpunonu, P.. (2010). A statewide prescription monitoring program affects Emergency Department prescribing behaviors. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 56 (1), 19-23.

73. Drug Enforcement Administration. (March 2011). Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS) [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/arcos/index.html.

74. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

75. National Quality Forum (NQF) in 2007, released groundbreaking endorsed national voluntary consensus standards on evidence-based practices to treat substance use conditions. The NQF consensus standards provide clear guidance to the field on evidence-based practices that, if adopted in all healthcare settings, would substantially improve patient outcomes. The mission of the National Quality Forum is to improve the quality of American health care by setting national priorities and goals for performance improvement, endorsing national consensus standards for measuring and publicly reporting on performance, and promoting the attainment of national goals through education and outreach programs.

76. White, W. L., Evans, A. C., Albright, L.,& Flaherty, M. (2009). Recovery management and recoveryoriented systems of care: Scientific rationale and promising practices. Counselor: The Magazine for Addiction Professionals, 10(1), 24-32.

77. Travis, J. (2005). But they all come back: Facing the challenges of prisoner reentry. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

78. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2007). Drug use and dependence, state,and federal prisoners, 2004. Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/dudsfp04.pdf.

79. Park, J. M., Metraux, S., & Culhane, D. P. (2005). Childhood out-of-home placement and dynamics of public shelter utilization among young homeless adults. Child & Youth Services Review, 27, 533-546.

80. Hipple, N. K., Corsaro, N., & McGarrell, E. F. (2010). The High Point Drug Market Initiative: A process and impact assessment, ProjectSafe Neighborhoods (Case Study Report #12). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, School of Criminal Justice.

81. Corsaro, N., Brunson, R., & McGarrell, E. F. (2009). Problem-oriented policing and open-air drug markets: Examining the Pulling Levers Deterrence Strategy. Crime & Delinquency, October 14. doi: 10.1177/0011128709345955.

82. Frabutt, J. M., Shelton, D. L., DiLuca, K. L., Harvey, L. K., & Hefner, M. K. (2009). A collaborative approach to eliminating street drug markets through focused deterrence. Retrieved from

http://www1.cj.msu.edu/~outreach/psn/DMI/HighPointEvaluation.pdf.

83. The new DMI sites are: Flint, MI; Guntersville, AL; Jacksonville, FL; Lake County (Gary), IN; Montgomery County (Damascus), MD; New Orleans, LA; and Roanoke, VA.

84. Kennedy, D. M., & Wong, S. L. (2009). The High Point Drug Market Intervention strategy. Retrieved from

http://www.cops.usdoj.gov/files/RIC/Publications/e08097226-HighPoint.pdf.

85. National Network For Safe Communities. (October 8, 2010). Providence. Retrieved from

http://www.nnscommunities.org/PROVIDENCE_FINAL.pdf.

86. National Network For Safe Communities. (October 8, 2010). Providence. Retrieved from

http://www.nnscommunities.org/PROVIDENCE_FINAL.pdf.

87. National Network For Safe Communities. (October 8, 2010). Providence. Retrieved from

http://www.nnscommunities.org/PROVIDENCE_FINAL.pdf.

88. National Drug Courts Institute. (December 2010). Unpublished count. Retrieved from http://www.ndci.org/ndci-home/2010.

89. See R2P translating drug court research into practice webpage at http://research2practice.org/ for more information.

90. National Institute of Justice. (n.d.) Ongoing drug court research: NIJ’s Multisite Adult Drug Court Evaluation (MADCE). Retrieved from http://www.nij.gov/nij/topics/courts/drug-courts/madce.htm.

91. West, H. C., Sabol, W. J., &. Greenman, S. J. (2010). Prisoners in 2009. (NCI 231675). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

92. Messina, N., Burdon, W., Hagopian, G., & Prendergast, M. (2006). Predictors of prison-based treatment outcomes: A comparison of men and women participants. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32(1),7-28.

93. Glaze, L. E., & Maruschak, L. M. (2010). Parents in prison and their minor children. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

94. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD All findings in the report are annual averages based on combined 2005 to 2008 data.

95. Committee includes the Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, Justice, Education, Defense, Agriculture, State, and Housing and Urban Development.

96. Department of Defense. (2009). Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel. Retrieved from http://www.tricare.mil/2008HealthBehaviors.pdf.

97. Department of Defense. (2009). Survey of Health Related Behavior Among Active Duty Military Personnel. Retrieved from http://www.tricare.mil/2008HealthBehaviors.pdf.

98. Dougherty, P. H. Statement of Peter H. Dougherty, Director, Homeless Veterans Programs; Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs; Department of Veterans Affairs; before the U.S. Senate; Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Subcommittee on Housing, Transportation, and Community Development. Hearing, November 10, 2009. Retrieved from http://banking.senate.gov/public/index.

cfm?FuseAction=Files.View&FileStore_id=a74d5b9d-20b3-4fae-8cf4-3fde5819d779.

99. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

100. American Indians and Crime: A BJS Statistical Profile, 1992-2002, by Steven Perry, Dept of Justice, NCJ 203097, Dec 2004.

101. American Indians and Crime: A BJS Statistical Profile, 1992-2002, by Steven Perry, Dept of Justice, NCJ 203097, Dec 2004.

102. American Indians and Crime: A BJS Statistical Profile, 1992-2002, by Steven Perry, Dept of Justice, NCJ 203097, Dec 2004.

103. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010). Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. (Vol. 1).(Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings). Rockville, MD.

104. Hawken, A., & Kleiman, M. (2009). Managing drug involved probationers with swift and certain sanctions: Evaluating Hawaii’s HOPE. Retrieved from www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/229023.pdf.

105. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2011). Reentry Trends in the U.S. Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/reentry/recidivism.cfm.

106. Pew Center on the States. (2007). Illinois. Retrieved from http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/uploadedFiles/IL%20State%20Profile%202-22-07.pdf.

107. Event deconfliction ensures law enforcement agencies working in close proximity of each other are immediately notified when enforcement actions are planned in a manner that threatens effective coordination or that compromises enforcement operations. Notification of such conflicts enhances officer safety and promotes the coordination of operations in a multi-agency environment. Similarly, target deconfliction alerts

investigators when there is an investigatory cross-over by enforcement agencies. Notification of duplicate targets encourages investigators to share information and resources.

108. A six-million-square-mile area, including the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and Eastern Pacific. The path(s) used by drug traffickers to transport illicit drugs to their market. Geographically, these paths normally connect, but do not include, the source and arrival zones. (Source – National Interdiction Command and Control Plan – March 17, 2010, Glossary of Terms).

109. See NIJ’s Drugs and Crime Research: Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Programs at

http://www.nij.gov/topics/drugs/markets/adam/#meetings.

110. Lacey, J. H., Kelley-Baker, T., Furr-Holden, D., Voas, R. B., Romano, E., Ramirez, A., …Berning, A. (2009). 2007 National roadside survey of alcohol and drug use by drivers: Drug results. (DOT HS 811 249). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

111. National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2010). Traffic safety facts: Drug involvement of fatally injured drivers. (DOT HS 811 415). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

112. Visit NIJ’s webpage for more information at http://www.nij.gov/nij/topics/corrections/community/drug-offenders/hawaii-hope.htm.

113. Visit NIJ’s webpage for more information at http://www.nij.gov/nij/topics/corrections/community/drug-offenders/decide-your-time.htm.

Bar code

NCJ 234320

ONDCP National Drug Control Strategy 2011

*NCJ~234320*