FACT SHEET: Progress in Our Ebola Response at Home and Abroad

Today, approximately 10 months since the first U.S. personnel deployed to West Africa to fight Ebola, we mark important milestones in our response to the epidemic and chart the way ahead. In keeping with the President’s charge that we tackle Ebola as a national security priority, we built, coordinated, and led an international response—involving thousands of personnel, both U.S. and international, civilian, and military—to fight the disease at its source. All the while, we enhanced our preparedness to encounter Ebola on our shores, establishing comprehensive measures to screen and detect the disease in travelers, while strengthening our capacity to diagnose, isolate, and treat any patients safely. This response showcased American leadership at its finest on the world stage, just as we came together as a nation to fortify our domestic resilience in the face of understandable apprehension. To be sure, our tasks are far from complete; we will keep working to meet this challenge until there are zero cases in West Africa and our domestic infrastructure is fully completed. Our focus now turns to consolidating that substantial progress as America today marks the next phase of our response.

As we mark this transition, today President Obama will host at the White House some of those responsible for these substantial gains. In preparation for this event, Ron Klain, the outgoing Ebola Response Coordinator, provided the President with a comprehensive update on our progress. As he told the President, Americans should be proud of what we, together as a nation, have accomplished, even as we must not lose sight of the challenges that remain and the urgent tasks ahead.

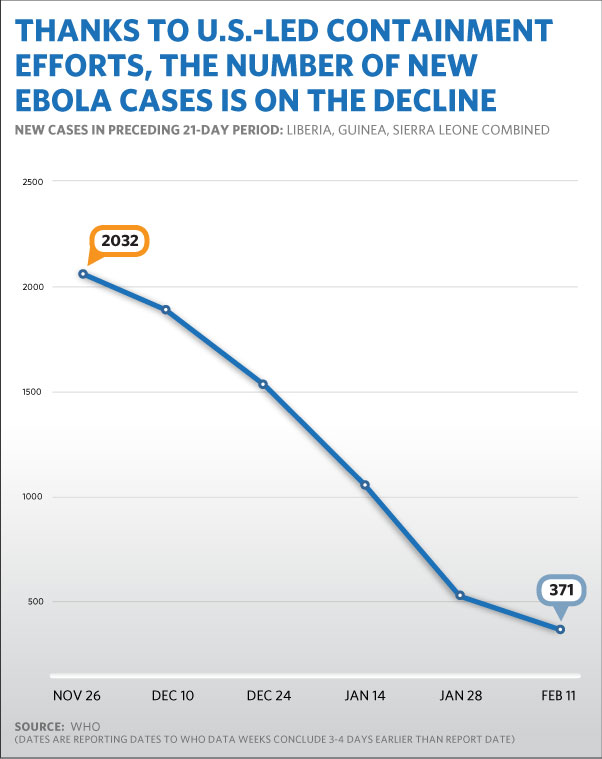

Together with our international partners – and the people of the three nations themselves – we have bent the curve of the epidemic and placed it on a much improved trajectory. We have gone from over 1,000 new suspected, probable, and confirmed Ebola cases a week in October, to roughly 150 new confirmed weekly cases in the most recent reports. Liberia has reported only a handful of new cases per week, a drop of well over 90 percent. Significant declines also have been reported in Sierra Leone from the epidemic’s peak. Among the accomplishments in this response:

- We ramped up the civilian response to treat Ebola patients, trace their contacts, promote safe burials, and increase community knowledge, resulting in more than 10,000 U.S. Government-supported civilians now on the ground in West Africa;

- In Liberia, U.S. personnel, both civilian and military, trained more than 1,500 healthcare workers, enabling them to provide safe and direct medical care to Ebola patients;

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sent nearly 1,000 civil servants on international deployments to support the Ebola response;

- The U.S. Government facilitated the construction of 15 Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) in the region, of which 10 were built by U.S. service members, along with a medical unit in Monrovia, Liberia, used to treat infected healthcare workers. These facilities have enabled the testing and isolation of hundreds of patients;

- We supported the establishment of core public health management of the epidemic such that in all three countries, there are now functioning public health emergency operations centers, laboratory testing capabilities, enhanced coordination, and rapid response capabilities; and,

- U.S. leadership galvanized a robust international response comprised of over 62 countries contributing more than $2 billion as well as thousands of personnel and wide-ranging resources.

Here at home, our response was methodical and guided by the science as we stood-up and enhanced our domestic preparedness. We are much better prepared to identify, isolate, and treat anyone who presents with the disease. Among our specific domestic accomplishments:

- We established a system for monitoring all arriving travelers from countries with widespread transmission. The regime is comprised of screening and daily symptom checks, including in-person examinations for those at elevated risk, covering more than 99 percent of all arriving travelers subject to this regime;

- We devised and implemented a system of nationwide Ebola Treatment Centers (ETCs)—facilities designed to treat an Ebola patient safely and effectively—resulting in a network that places more than 80 percent of all arriving travelers from the affected countries within 200 miles of one of the 51 Centers;

- We accelerated development of diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics to identify, prevent, and treat the disease. Two vaccine candidates have completed Phase 1 trials, while Phase 2/3 vaccine candidate trials are underway in West Africa with therapeutics trials starting shortly. Three rapid point-of-care tests are being evaluated; two of them are in field trials, and another will be ready for field trial in the near future; We are taking steps to ensure commercial-scale manufacturing capabilities for the successful vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics for potential future needs; and

- We worked with a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers to secure the resources necessary to confront this disease both at home and abroad, leading a Congressional majority to approve $5.4 billion in emergency funding in December 2014.

A Successful Strategy to “Bend the Curve” of the Epidemic in West Africa

Since its launch in March 2014, the U.S. Ebola response has deployed more than 3,500 Department of Defense (DoD), CDC, U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) Commissioned Corps, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) personnel to the affected region. As a result of this strategy – along with international partners, non-governmental organization, international responders, and others -- we have helped bend the epidemiological curve and averted the horrific worst-case scenarios predicted by computer modeling at the beginning of the response. We have since seen drastic declines in the case counts in all three countries.

- In Liberia at the peak of the outbreak, there were 119 confirmed cases per week, and today there were 3 confirmed new cases this week.

- In Sierra Leone at the peak of the outbreak, there were 534 confirmed new cases per week, and today there are 76 confirmed new cases this week.

- In Guinea at the peak of the outbreak, there were 148 confirmed cases per week, and today there are 66 confirmed new cases this week.

This progress was predicated on a global response, in which America’s whole-of-government strategy has included both civilian and military personnel. Over 10,000 U.S. Government-supported personnel are now engaged in the Ebola response in West Africa, treating patients, tracing contacts, promoting safe burials, and educating communities, among other core tasks.

Isolation and Treatment Facilities: The U.S. Government facilitated the construction of 15 ETUs in the region, of which 10 were built by DoD. All had been completed by early January and have helped isolate of hundreds of Ebola patients and those suspected of having the disease. We also provided materials and operational support to several other ETUs, Transit Centers, and Limited Care facilities in the affected countries, resulting in a network of isolation and treatment facilities critical to disrupting chains of transmission.

- Additionally, DoD constructed the Monrovia Medical Unit (MMU) for treatment of Ebola-infected healthcare workers with staffing by the USPHS Commissioned Corps. DoD is now in the process of transitioning non-clinical management to USAID. Since November, the MMU has admitted and cared for over 36 patients from 9 nations. Over 200 officers of HHS’ U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps have deployed and staffed the facility.

Provision of Medical and Relief Supplies: USAID expanded the pipeline of medical equipment and supplies, airlifting to the region more than 400 metric tons of personal protective equipment (PPE), infrared thermometers, chlorine, and plastic sheeting for the construction of ETUs. In addition, DoD is in the process of delivering 1.4 million sets of PPE to Liberia. CDC has provided the technical expertise to direct purchasing requests for both ETU and frontline healthcare facility PPE and infection control resource needs.

Safe Burial Teams: Unsafe burial practices accounted for many of the transmissions throughout the region, leading us to prioritize the creation and support of Safe Burial Teams. U.S. partners have established and operated over 190 burial teams in the region—70 in Liberia, 50 in Sierra Leone, 70 in Guinea.

Laboratory Testing Facilities: DoD has provided seven mobile laboratories to the region, reducing the time to diagnosis from days to hours. These labs have tested more than 4,000 samples since September 2014. CDC is also supporting laboratories in Liberia and Sierra Leone, leading to efficient and rapid Ebola testing. CDC continues to staff a laboratory in Bo, Sierra Leone, that has tested more than 10,000 samples and has applied innovations to improve throughput. CDC’s Lab Task Force has initiated trainings and provided guidance in partnership with at-risk, unaffected countries to improve their response capacity in the event that an Ebola case is imported into their country.

Contact Tracing and Case Investigation: USAID and CDC partners have pursued an aggressive case investigation and contact tracing effort designed to identify and monitor all active chains of transmission in the region. As of early February, nearly all new cases in Liberia were diagnosed in known contacts of Ebola patients, indicating the tremendous progress we have made. CDC has deployed teams to district/county prefecture levels to assist with the response.

Training Healthcare Workers: In Liberia, DoD has trained more than 1,500 health care providers, enabling them to provide safe and direct medical care to Ebola patients. In Sierra Leone and Guinea, USAID-supported partners have trained thousands of health care workers in infection control standards and Ebola case management to ensure they have resources and skills to safely care for Ebola patients. CDC, meanwhile, has trained 690 master trainers and more than 18,000 frontline healthcare staff and has conducted 231 facility assessments. As of January, CDC had trained more than 450 responders in the United States prior to their work in West African ETUs.

Community Outreach and Social Mobilization: USAID has supported programs to reach millions across the region with messages on Ebola identification and prevention, teaching them how to protect themselves and their loved ones. USAID also enabled mobilization teams to go door-to-door in communities across the region with potentially life-saving information. Additionally, CDC and its partners have engaged with communities in the affected countries through influential community members, such as community leaders, religious leaders, journalists, celebrities, and others to foster widespread use of accurate, consistent messages.

Exit Screening: CDC has worked with international partners to increase capacity in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea to identify travelers who may be experiencing symptoms of Ebola or other diseases, educate travelers, prevent them from traveling within or beyond the region, and refer them for appropriate care as necessary.

Getting to Zero Cases in West Africa

We are encouraged by the declining number of new Ebola cases in West Africa, but remain concerned about a recent increase in cases in Guinea, and an inability to further reduce case counts in Sierra Leone. Moreover, given that a single case can lead to flare-ups of the virus, we must not lose focus. We will continue to pursue our flexible and adaptable strategy, meeting the evolving conditions on the ground until we have reached zero cases. For example, just as we have scaled the ETU isolation and treatment capacity to reflect lower case rates, we are now ramping up aggressive case finding and contact tracing efforts to hunt remaining cases. We are training health staff on infection prevention and control measures to ensure that, as regular health services resume across the region, they will be able to identify, triage, isolate, and treat any additional cases. Finally, we will continue public awareness campaigns and outreach so that communities remain vigilant and prepared.

With over 10,000 civilians engaged in this effort with U.S. support, we will beat the virus, launch recovery efforts that strengthen the health systems, prepare for future Ebola or other contagious disease outbreaks, and contribute to stronger global health security.

With the improved epidemiological outlook, we are planning for the return to the United States of the majority of the troops deployed in Operation United Assistance (OUA), the U.S. Military’s Ebola response. Of the 2,800 troops deployed, approximately 1,500 are already back in the United States, and nearly all of those remaining will return home by April 30. OUA will continue after April 30 with a complement of approximately 100 DoD personnel who, leveraging an already strong military-to-military partnership with the Armed Forces of Liberia and other regional partners, will remain steadfast in supporting Ebola response efforts. Other response functions have been or will be transitioned to civilian personnel.

- Throughout the transition, DoD will remain prepared to respond to Ebola-related contingencies in West Africa as requested by USAID. Military personnel will revert the OUA Intermediate Staging Base in Dakar, Senegal to Cooperative Security Location (CSL) Status on March 2, 2015, where it will remain available to support a range of missions. DoD is identifying the right forces to support follow-on activities, including the headquarters cell, augmentation for Operation ONWARD LIBERTY, the Defense Preparedness Program, and additional security cooperation activities.

- The Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (CTR) is preparing to build out its biosurveillance capacity, including related biosecurity and biosafety capabilities, in West Africa and expand this capacity to the rest of the continent over the long-term to augment partner country capability to detect and report outbreaks of dangerous infectious diseases.

- DoD and the Government of Liberia agreed that in the near term two mobile labs will be repurposed to support sustainable diagnostic testing for biosurveillance. They also agreed that CTR will continue to support the Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research through training, equipping, facility upgrades, and sustainment plans.

As DoD draws down, the United States will continue to support the regional governments alongside the international humanitarian and public health community. Working together, the goal remains to get to zero cases while building better and more resilient health systems and ensuring capacity to prevent, detect, and rapidly respond to future outbreaks through our Global Health Security Agenda. While the fight is far from over, we will also be helping health workers and health facilities to reopen their doors to treat malaria, catch up on immunizations for children, and keep pregnant mothers healthy. This objective will require a sustained U.S. engagement in the region.

Protecting Against Cases at Home

Just as we mounted an aggressive whole-of-government response to bring the epidemic under control in West Africa, we took prudent measures to respond to threat of Ebola cases to the United States. Since early October, CDC and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) personnel have conducted entry screening to detect signs of illness or potential exposure to Ebola among all passengers arriving in the United States who recently traveled to, from, or through Guinea, Liberia, or Sierra Leone. Entry screening was expanded to include Mali while cases were being reported in that country and potential spread through international air travel remained a concern.

- Since entry screening began, 7,700 adults and children have been screened. All of them have been subject to a 21-day monitoring regime which enables prompt detection, isolation, and treatment of anyone who is diagnosed with Ebola.

- We developed national guidance on Ebola exposure risk levels and relevant public health actions. This guidance included recommendations for public health officials to actively monitor the health of recently-arrived travelers who have some degree of identifiable risk each day for 21 days from the date of their last possible exposure. If a traveler returning from the affected countries were to develop symptoms, he or she would be able to get care immediately and prevent transmission to others.

- Each traveler being monitored now also receives a Check and Report Ebola (CARE) Kit, a 21-day pre-paid cell phone, a digital thermometer, and meets with a trained educator to learn about daily symptom monitoring and reporting.

- CDC has given out more than 5,700 CARE Kits, including more than 3,800 CARE cell phones, provided to the U.S. Government free-of-charge by the non-profit CDC Foundation.

- CDC provided guidance and resources to state and local health partners to implement active and direct active monitoring. In this way, every person arriving in the US from the three West African nations is subjected to a daily monitoring regime for a 21-day period.

Enhancing Domestic Preparedness

On top of our entry screening measures, we undertook a concerted effort to ensure that, if we needed to treat an Ebola patient, our national health system would be prepared to spot, diagnose, transport, and treat the patient effectively without infecting others. CDC and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) at HHS led efforts to enhance domestic preparedness. CDC implemented a series of tools to assess and improve facility readiness, allowing us to have confidence in our nationwide ability to respond to any additional cases at home.

CDC released guidance to prepare U.S. healthcare facilities for Ebola through a 3-tiered approach: ETCs, assessment hospitals, and frontline healthcare facilities.

Ebola Treatment Centers. State and local public health officials, with technical assistance from CDC and ASPR, have collaborated with hospital officials to increase domestic capacity to treat Ebola patients. Prior to October, there were three facilities in the United States recognized for their biocontainment capability for treating Ebola and other infectious diseases: Emory University Hospital, University of Nebraska Medical Center, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center. Today, we have a network of 51 Ebola treatment centers in 16 states and the District of Columbia, with 72 available beds.

- Hospitals with treatment centers have been designated by state health officials, based on a collaborative decision with local health authorities and the hospital administration, to serve as treatment facilities for Ebola patients. ETCs are staffed, equipped, and have been assessed to have the capability, training, and resources to provide the treatment necessary to care for an Ebola patient.

- ETCs have been assessed by a CDC Rapid Ebola Preparedness (REP) team, a concept created in October that brings together experts in all aspects of Ebola care, including staff training, infection control, and PPE use. In total, CDC REP teams have visited 80 facilities in 20 states and the District of Columbia.

- Because of this approach, more than 80 percent of travelers returning from West Africa are now within 200 miles of an Ebola treatment center and could be safely transported to one via ambulance, if necessary. (Medevac capacity is available for the other returning travelers.)

Assessment Hospitals. CDC and ASPR have also made progress working with state and local public health officials in identifying Ebola assessment hospitals. Assessment hospitals have been identified by state health officials as the point of referral for individuals who have a travel history and symptoms compatible with Ebola.

- These hospitals have the capability to evaluate and care for individuals who have a travel history and symptoms compatible with Ebola for up to 96 hours and initiate or coordinate Ebola testing and testing for alternative diagnoses. These hospitals can either rule out Ebola or transfer the individual to an Ebola treatment center, as needed.

- States with the majority of travelers from the affected countries have developed strategies to evaluate persons under investigation and to provide care for up to 96 hours at an assessment hospital while Ebola testing can be arranged.

Frontline Healthcare Facilities. Acute care hospitals and other emergency care settings can also serve as frontline healthcare facilities. Frontline healthcare facilities are prepared to identify a person with a travel history, potential exposure, and symptoms suggestive of Ebola.

- These facilities have the ability to identify and isolate patients with a relevant exposure history and signs or symptoms compatible with Ebola.

- Frontline healthcare facilities have enough PPE to last for 12 to 24 hours of care and can prepare a patient for transfer to an assessment hospital or treatment center, if needed.

- Regardless of a facility’s pre-designated role, CDC is ready to support any U.S. hospital or medical clinic that identifies a probable Ebola patient by sending a CDC Ebola Response Team (CERT) within a few hours of a highly suspected or confirmed diagnosis. The CERT Teams will help clinicians and state and local public health practitioners to consistently follow strict protocols that protect the patient and health care workers. These teams are operational and have already been called on for assistance. CDC has also provided additional resources and guidance to assist with hospital readiness.

Ebola Testing Laboratories. Just as we have expanded the network of hospitals capable of responding to an Ebola patient, CDC’s Laboratory Response Network (LRN) has grown the network of laboratories able to test a potential Ebola specimen. In order to qualify as an LRN Ebola testing lab, a facility must have an appropriate and functioning biosafety level 3 laboratory, the necessary test reagents, appropriate staff training, and the proper PPE to perform the assay safely. A testing lab demonstrates competency by successful completion of a quality assurance panel. Upon completion and evaluation of the panel, the laboratory is considered approved to test for Ebola using the DoD assay.

- Prior to the current outbreak in West Africa, Ebola could be confirmed only at the CDC laboratory in Atlanta, Georgia. In August 2014, 13 LRN laboratories in 13 states were qualified to test for Ebola. As of January 31, 2015, there are 55 LRN laboratories in 43 states that are approved to test for Ebola using a DoD test authorized for emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Since we have more than quadrupled our capacity to test for Ebola, turnaround time for Ebola results dramatically decreased in the United States.

- With the expansion of testing services, a test result is typically available 4 to 6 hours after receipt of a specimen in the lab. This allows clinicians to make patient-care decisions in a shorter timeframe and protects the American public from unnecessary exposures. By comparison, the first Ebola specimen domestically tested at Mt. Sinai in August 2014 took close to 24 hours to complete.

- State and local public health laboratories have been actively involved in the response. To date, 25 laboratories have performed 90 tests using the DoD Assay. Since the authorization of the first test for the detection of Ebola in August, there are now a total of seven diagnostic tests that have been authorized for emergency use by FDA. While there are commercial Ebola tests available for qualified hospital laboratories, test results must be confirmed at CDC.

Healthcare Worker Outreach and Training. We have conducted extensive outreach to the healthcare community, including hospitals, clinicians, healthcare unions, and professional associations. Our outreach has focused on training and on preparing facilities to identify, isolate, diagnose, and care for patients under investigation for Ebola. CDC conducts daily and weekly calls and webinars to provide a forum for partners to have questions answered directly by CDC staff.

- Since the start of the outbreak, CDC has educated more than 150,000 healthcare workers via more than 150 webinars and conference calls with professional organization members.

- CDC has also conducted numerous live, onsite training events for healthcare professionals. These events have reached more than 6,500 people in-person and over 20,000 people from 10 countries via live webcast. CDC partnered with Partnership for Quality Care, hospital associations, and healthcare unions on three live events.

Developing Countermeasures to Prevent and Treat Ebola

Over the longer-term, vaccines and therapeutics will be a key tool in our arsenal to address future epidemics, and we have significantly ramped up development and clinical trials of vaccine and drug candidates. While no therapeutics or vaccines have yet been proven safe and effective for treating or preventing Ebola, HHS—led by efforts at NIH, CDC, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and the FDA—has made tremendous progress and is expediting the human clinical trials of several Ebola vaccine and therapeutic candidates.

Ebola Vaccine Development. The U.S. Government is supporting the development of multiple Ebola vaccine candidates in various stages of development. Two vaccine candidates—ChAd3 and VSV-ZEBOV—have completed Phase 1 human clinical trials and are now being tested in a Phase 2/3 clinical trial in Liberia and in the near future in a phase 3 trial in Sierra Leone. Other vaccine candidates are either in Phase 1 testing or are expected to begin Phase 1 testing during the year. FDA has held meetings with the sponsors of several other vaccine candidates, which are a few months to approximately a year away from the start of clinical trials.

We achieved a major milestone on February 2 with the launch of the Partnership for Research on Ebola Vaccines in Liberia (PREVAIL) Phase 2/3 trial. The PREVAIL trial, which is designed to enroll approximately 27,000 healthy men and women in Liberia, is testing two experimental Ebola vaccines that have performed well in previous Phase 1 clinical trials. The two test vaccines include the cAd3 Ebola vaccine candidate, which was developed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and GlaxoSmithKline, and the VSV-ZEBOV vaccine, which was developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada and licensed to NewLink Genetics Corp. The government of Sierra Leone is collaborating with CDC to plan a large study there to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an Ebola vaccine candidate among health workers. This trial is anticipated to begin in the near future.

Ebola Therapeutics Development. Additionally, the U.S. Government is supporting the development of several investigational candidate therapeutics to treat patients infected with the disease. Some have already been employed in patients under compassionate usage in the United States, Western Europe, and Africa.

- ZMapp: Under contract with DoD’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) and BARDA, Mapp Biopharmaceutical is developing Zmapp, a candidate therapeutic with antibodies that are produced in specially grown tobacco plants. Only limited quantities have been produced to date. NIAID supported the preclinical safety studies. BARDA is sponsoring the manufacturing of ZMapp for clinical studies to determine the product’s safety and efficacy. ZMapp has shown evidence of antiviral activity in animal models of Ebola infection. Clinical studies are anticipated to start in February 2015 in Liberia and in North America. This therapeutic candidate has been used under an emergency investigational new drug (eIND) application in Ebola-infected patients in the United States, and also has been administered in Africa, and elsewhere. Mapp Biopharmaceutical is developing ZMapp with BARDA support.

- TKM-Ebola: TKM-Ebola has undergone testing in nonhuman primates and has shown evidence of activity against Ebola virus. This therapeutic candidate has been used under an IND in some Ebola-infected patients in the United States. TKM-Ebola is produced by the Canadian company Tekmira Inc. under a contract from the Joint Program Executive Office for Chemical and Biological Defense.

- BCX4430: BCX4430 is a small molecule drug developed by BioCryst with support from NIH. Preliminary investigations have shown antiviral activity against a range of viruses, including Ebola. Results from a nonhuman primate Ebola challenge study have shown evidence of activity. NIH began Phase 1 clinical studies in healthy volunteers in December 2014 to determine safety and a treatment dosage. BioCryst is in discussions with BARDA to improve drug manufacturing and conduct future clinical studies.

FDA continues to work with product sponsors, U.S. government funding agencies, and international partners, to clarify data, clinical studies, and regulatory requirements necessary to facilitate the development and availability of the most promising vaccines and therapeutics that could potentially mitigate the current Ebola outbreak, as well as potential future outbreaks. FDA will use its flexible regulatory framework, such as issuing Emergency Use Authorizations, to make available investigational in vitro diagnostics needed to detect Ebola in West Africa, and will continue to work with diagnostic manufacturers and U.S. Government partners to facilitate development of diagnostics for Ebola, as well as other potential emerging infectious disease threats.

Institutionalizing Domestic Preparedness

The current Ebola outbreak, combined with information from other outbreaks of both recognized and novel pathogens in U.S. healthcare settings, suggests that additional efforts are needed to support domestic preparedness by enhancing the ability to prevent transmission of infectious diseases in healthcare settings. As such, HHS will convert at least 10 of the Ebola Treatment Centers into long-term Regional Ebola and Pandemic Treatment Centers. These facilities will have heightened and long-term readiness capabilities to treat Ebola and other similar dangerous diseases for years to come.

CDC, meanwhile, will build upon existing state and local health department infection control infrastructure to bolster infection control training and competency across the healthcare delivery system through a combination of on-site assessments, training, and policy implementation. Working with partners in healthcare, health departments will:

- Perform targeted assessments of infection control competency at healthcare facilities;

- Identify gaps in infection control performance and facilitate/implement programs and policies to address these gaps; and

- Implement response and prevention activities aimed at making a large impact on reducing transmission of pathogens in healthcare settings.

ASPR and CDC also plan to implement peer-review and recognition as well as healthcare worker training at regional Ebola and Other Special Pathogen Treatment Centers, state Ebola treatment centers, and assessment hospitals. Experts from healthcare institutions with experience in caring for a patient with Ebola will implement targeted training, including hands-on training, for these facilities and staff, as well as state health department employees where Regional Ebola and Other Special Pathogen Treatment Centers, state Ebola treatment centers, and assessment hospitals are located.

- CDC is working with numerous academic and industry partners to explore innovative strategies for preventing healthcare-associated transmission of Ebola and/or infectious pathogens that can be spread by the same mechanism as Ebola.

Going forward, CDC is offering states an additional $145 million in funding for additional measures that could pay dividends in response to Ebola or another contagious disease, including:

- Accelerating preparedness planning within state and local public health authorities for Ebola and other infectious diseases;

- Improving and promoting operational readiness for Ebola and other infectious diseases,

- Enhancing laboratory capabilities; and,

- Supporting state and local Ebola public health response efforts.

Securing Resources to Sustain Our Progress at Home and Abroad

Since the first cases of Ebola were reported in West Africa, Americans have understood the need to contain the disease at its source, while fortifying our defenses and preparedness at home. As the epidemic intensified, lawmakers from both parties understood that an effective, whole-of-government response required resources commensurate with the challenge. The Administration worked closely with Congress in a bipartisan way to fund the emergency request. In December 2014, the President was pleased to sign legislation that included $5.4 billion in emergency funding to implement a comprehensive strategy to end the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and advance our preparedness at home. The bill includes funding for the key agencies and departments involved in the response.

CDC—$1.7 billion. The bill includes funding to prevent, detect, and respond to the Ebola epidemic both at home and abroad for the following activities:

- Fortify domestic public health systems and advance U.S. preparedness through Ebola Treatment Centers coordinated by state and local public health departments;

- Improve Ebola readiness through additional support to the Public Health Emergency Preparedness program;

- Procure PPE for the Strategic National Stockpile.

- Increase support for monitoring travelers at U.S. airports and provide for the transportation, medical care, treatment, and other related costs of persons quarantined;

- Provide medical worker-based training to prevent and reduce exposure of hospital employees, emergency responders, and other workers who are at risk of exposure to Ebola;

- Control the epidemic in the hardest hit countries in Africa by funding activities such as: infection control; contact tracing; laboratory surveillance and training; emergency operation centers and preparedness; and education and outreach;

- Conduct evaluations of clinical trials in affected countries to assess safety and efficacy of vaccine candidates; and,

- Enhance global health security capacity in vulnerable countries to prevent, detect, and rapidly respond to outbreaks before they become epidemics by standing up emergency operations centers; providing equipment and training needed to test patients and report data in real-time; providing safe and secure laboratory capacity; and developing a trained workforce to track and end outbreaks before they become epidemics.

Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund—$533 million. The bill includes funding to respond to patients with highly-infectious diseases such as Ebola, including for the purchase of and training on the use of PPE at hospitals across the United States and to support ETCs. The funding will also support the nation's approximately 500 health care coalitions to support the purchase of PPE and training for hospitals, emergency medical services providers, and ambulatory care facilities to address Ebola. The bill also provides transfer authority across HHS to meet critical needs that may arise rapidly. For example, resources could be used to scale Ebola response efforts in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and neighboring countries if the outbreak spreads or if the caseload dramatically increases. As HHS continues its work to develop an Ebola vaccine, these resources could also be used to scale-up production and implement a vaccination campaign.

BARDA—$157 million. The bill includes resources for BARDA to manufacture vaccines and synthetic therapeutics for use in clinical trials.

NIH—$238 million. The bill includes funding for immediate response for advanced clinical trials to evaluate the safety and efficacy of investigational vaccines and therapeutics.

FDA—$25 million. The bill includes funding for immediate response for development, review, regulation, and post-market surveillance of an Ebola vaccine and therapeutics.

Department of State and USAID—$2.5 billion. These resources will allow USAID to scale up the U.S. foreign assistance response to contain the Ebola crisis in West Africa and assist in the region’s recovery from the epidemic. The bill funds USAID to expand emergency assistance to contain the epidemic, address humanitarian needs, and support the recovery of affected countries in the region. The funds also allow USAID to support the medical and non-medical management of ETUs and community care facilities; provide them with PPE and supplies; strengthen the regional logistics network to support the international crisis response; increases the number of safe burial teams; address food insecurity and other second-order impacts in affected communities, such as adverse effects on maternal and child health; and bolster community education efforts critical to prevent the spread of the disease. The bill also provides authority to reimburse accounts at State and USAID that funded activities to contain and end the Ebola epidemic prior to enactment.

DoD—$112 million. These funds will be allocated for the following purposes: $33 million for DARPA for Phase I clinical trials of experimental vaccines and therapeutics; $12 million for diagnostic efforts; $50 million to the Chemical and Biological Defense Program to continue work on vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostic systems that could mitigate the spread of Ebola; and $17 million for the procurement of detection and diagnostic systems, mortuary supplies, and isolation transport units.