The G-20 and the Global Economy

“The G-20 and the Global Economy”

As Prepared for Delivery

Deputy National Security Advisor Caroline Atkinson

November 4, 2015

Peterson Institute for International Economics

Thank you Adam for the kind introduction.

As most of you are aware, in just over a week President Obama will be travelling to Antalya, Turkey, for the G-20 summit—the 10th G-20 Leaders’ Summit, and President Obama’s 9th. The G-20 is as relevant as ever, against the backdrop of a global economy that has consistently underperformed expectations since the recovery began. And given the degree of interdependence and interconnectedness in today’s global economy, the world needs a forum that brings together the major advanced and emerging economies.

While G-20 finance ministers had met since 1999, G-20 leaders gathered for the first time in Washington in 2008. Since then, policy responses have been tested, and the lessons learned over this history help point to where we need to go next. The G-20’s efforts to date speak to its power as an emerging forum – and suggest that the hard work of coordinating policy among the major economies can pay off.

In some areas, these successes have taken the form of notable joint action – on financial regulation, for example. In others, these successes are best observed by comparison to the counterfactual – what might have been had we not acted. And while I will focus today on the global economy, the G-20 leaders have also helped marshal a collective response to other social and political challenges, like Ebola, hydrofluorocarbons, and worker safety.

I’d like to use my remarks today to examine what the G-20 has accomplished to date, the challenges facing us today, and what the G-20 can do to address these challenges – specifically with regard to the G-20’s core aim of promoting strong, sustainable, and balanced global growth.

Where We Started and What We Accomplished

When G-20 leaders were meeting for the first times in 2008 and 2009, the global economy was in the midst of a historic crisis. A repeat of the Great Depression was very much a possibility. Cross-border coordination in financial regulation and supervision had proven woefully inadequate. Large imbalances had built up across the global economy.

In the United States, when President Obama took office in 2009, the economy was being hit by a negative shock that was in some respects worse than the one in the fall of 1929. U.S. households saw their net worth decline by more in 2008-2009 than they had in the first year of the Great Depression. The U.S. economy lost $13 trillion in wealth, 19 percent of total wealth – about five times the percentage reduction in wealth experienced at the onset of the Great Depression. Employment in the United States declined by 4 percent from 2008 to 2009, the same rate as from 1929 to 1930. Fears that we were heading into a global depression were not hyperbole: all available data suggested that this was the trajectory we were on.

At the same time, we had every reason to brace ourselves for another retreat into protectionism and beggar-thy-neighbor economic policies like competitive currency devaluation. Historical precedent suggested that the economic crisis that was unfolding would make global cooperation difficult, if not impossible.

So in April 2009, as G-20 leaders gathered in London for the second-ever G-20 summit, the task was both critical and daunting.

The leaders of the world’s largest economies “pledged to do whatever is necessary to:

o restore confidence, growth, and jobs;

o repair the financial system to restore lending;

o strengthen financial regulation to rebuild trust;

o fund and reform our international financial institutions to overcome this crisis and prevent future ones;

o promote global trade and investment and reject protectionism, to underpin prosperity; and

o build an inclusive, green, and sustainable recovery.”

“Ambitious” didn’t even begin to describe it.

Faced with economic calamity, the G-20 took action. Together, G-20 countries injected $5 trillion of global fiscal stimulus and mobilized an additional $1 trillion for international financial institutions to raise global output and support growth. Further, G-20 leaders also vowed that, contrary to what may have been expected given the global economic situation and historical precedents, they would not fall for the temptation of trade barriers and isolationism.

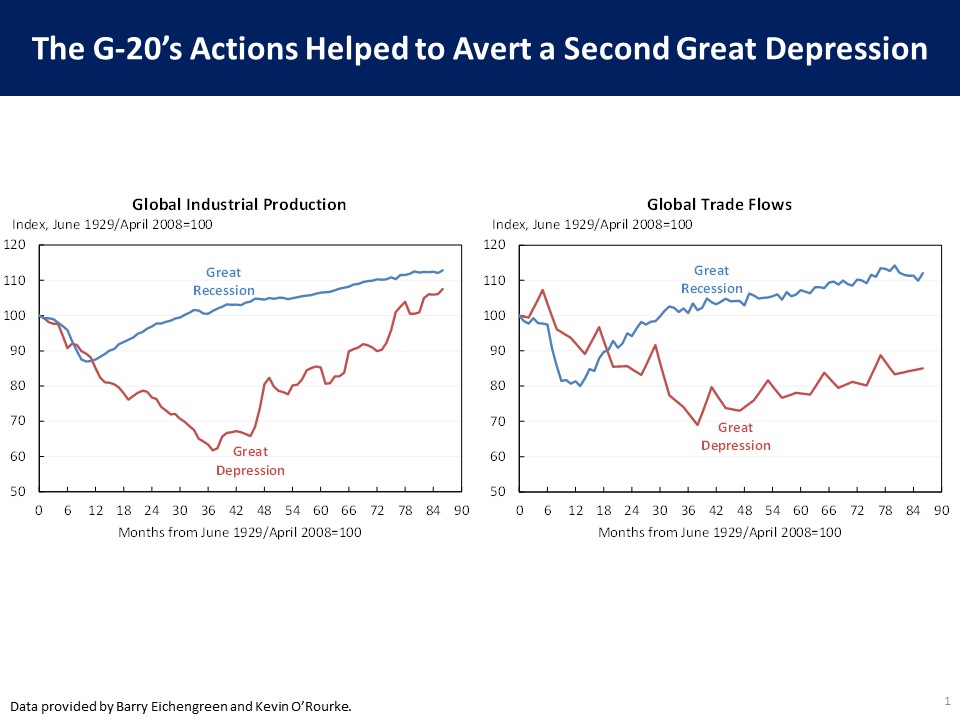

These steps – combined with the unprecedented monetary policy response in many countries – turned around the trajectory and allowed the world to avoid a far worse outcome than seemed possible, or indeed likely, in late 2008. Production fell about as sharply in the first year of the Great Recession as during the first year of the Great Depression. In the case of global trade, the initial plunge was steeper in the most recent crisis. However, both indicators also rebounded far more sharply and returned to their pre-crisis peaks years sooner than they did during the Depression. As described in the Pittsburgh declaration, in probably the shortest sentence ever in an official communique, “It worked.”

In 2009, G-20 leaders began a series of steps to rebuild the global economy on a stronger, more resilient footing. In the area of financial regulation, the Financial Stability Board has helped to coordinate the G-20’s financial reform agenda and to put in place international policies to end too-big-to-fail – including recently, the standard for Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) that G-20 leaders are expected to endorse in Antalya. The G-20 also set the stage for agreement on new international standards for bank capital, committed to making derivatives markets more transparent and safe, and launched work to address systemic risks in the shadow banking sector. And importantly, the G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors have adopted a series of increasingly robust commitments on exchange rates, in order to avoid the sort of external imbalances that in part contributed to the crisis. The G-20 also committed to move towards greener, more sustainable growth – which today is seen as a critical imperative. On tax, the G-20 has taken up the automatic exchange of tax information pioneered in the U.S. Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) to combat cross-border tax evasion. The G-20 has also worked with the OECD to develop a set of robust recommendations to address tax avoidance by multinational companies through the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process. The final recommendations arising from this process will be also be endorsed by G-20 leaders this year in Antalya. The G-20 further committed to reform the international financial architecture, and while we have made some progress in that regard, we unfortunately still require to Congressional approval in the United States to make good on the biggest piece of it: the 2010 IMF quota reforms.

The Framework for Strong, Sustainable, and Balanced Growth from 2009 to Today

The core economic commitment the G-20 made in 2009 was to promote strong, sustainable, and balanced growth. Debates over the nature of that commitment – and the appropriate policy response to achieve it – have been at the center of G-20 discussions over the past six years. I believe this brief but textured history is best understood in four stages.

First, there was the aggressive response to the crisis and the ambitious set of commitments in London that I described a moment ago. The need for a continued strong policy response was still evident when leaders met in Pittsburgh in September 2009. The Pittsburgh communique read, “We pledge today to sustain our strong policy response until a durable recovery is secured … We will avoid any premature withdrawal of stimulus.”

By mid-2010, however, the sentiment in the G-20 had begun to shift, and some countries grew increasingly concerned about rising debt levels and sanguine about recovery. The G-20 was not alone in this regard; the IMF and others were discussing how governments should exit from the stimulus they had implemented. In retrospect, the talk of “exit strategies” from stimulus was premature. At the June 2010 Toronto Summit, the communique underscored “the importance of sustainable public finances and the need for our countries to put in place credible, properly phased and growth-friendly plans to deliver fiscal sustainability.” It further stated, “Those countries with serious fiscal challenges need to accelerate the pace of consolidation.” Advanced economies committed to fiscal plans that would halve deficits.

By mid-2011 a new set of events had emerged that would further complicate the picture. The third stage of the G-20’s history – including the summits in Cannes in 2011 and Los Cabos in 2012 – was dominated by the European sovereign debt crisis and the risks it posed to global stability and growth. The Cannes declaration highlighted that “tensions in the financial markets have increased due mostly to sovereign risks in Europe,” while the Los Cabos declaration called on the Euro Area G-20 members to take action to “break the feedback loop between sovereigns and banks.”

Today, the Euro Area has largely pulled itself back from the brink, and we now are in what I would describe as the fourth stage, focused centrally on the need to strengthen growth. The St. Petersburg communique in 2013 emphasized growth and jobs and stated that “Our most urgent need is to increase the momentum of the global recovery.” Last year in Brisbane, leaders went a step further to isolate the main challenge. They stated, “The global economy is being held back by a shortfall in demand.” One year later, there can be no doubt that this challenge persists and will be central to the conversations in Antalya.

Looking across this history, we know that the G-20 was successful in averting a second Great Depression. We also know that the Euro Area has managed to avert a break-up, and that many economies have made significant progress in bringing down their deficits. Today, the issue confounding leaders and finance ministers is whether the G-20 can achieve a truly robust global economic recovery.

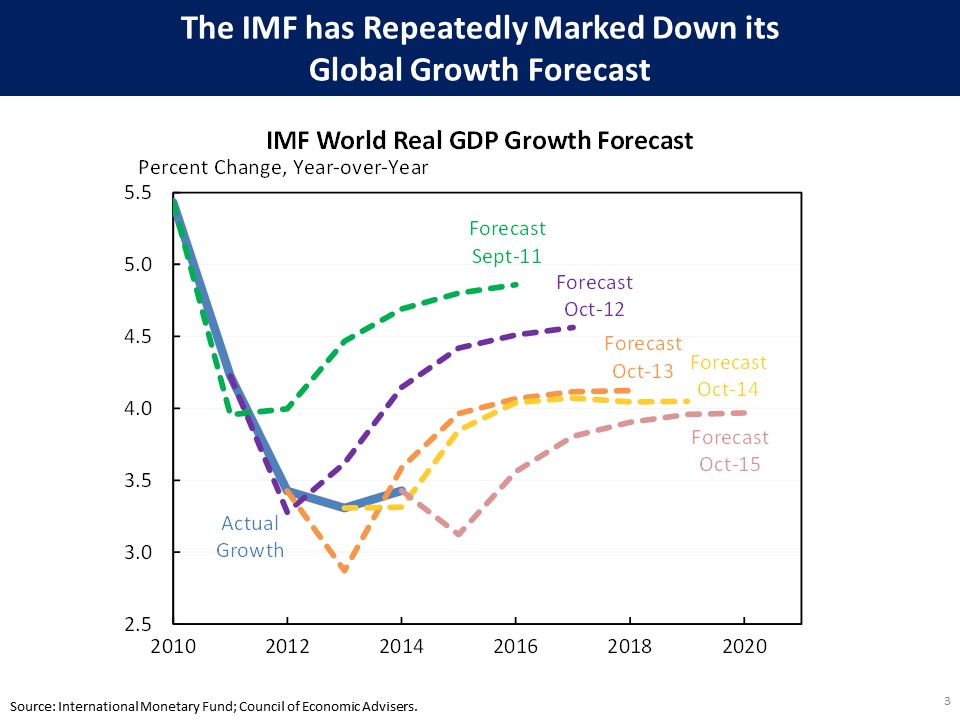

At the Brisbane Summit, G-20 leaders put forward national “growth strategies” that would collectively raise G-20 GDP by 2 percent by 2018. But while measures representing approximately a third of that growth target have been implemented over the past year, the G-20’s action on growth has not been sufficient. This is partly because the measures included in the national growth strategies were by design tilted towards structural reforms that will raise growth over the medium term, rather than near-term demand support. It is also because the global economy’s underlying trajectory has deteriorated: the IMF’s forecast for cumulative growth between 2014 and 2018 is now 2 percent less than the baseline envisaged in Brisbane, and global growth this year is expected to be at the slowest pace since the financial crisis. Of course, this is just the latest in a series of downward revisions to the IMF’s global growth forecast, and the IMF has not been alone; the world has consistently been over-optimistic about the economic outlook.

In short, the G-20’s efforts on growth are still a work in progress.

The U.S. voice in the G-20 has been focused on the need to take action, and it has been strengthened by our economic performance. In the United States, we pursued a multi-pronged approach that combined expansionary fiscal and monetary policy with short-term stabilization measures and financial reforms early on, as well as structural reforms in health, energy, and education. Today, U.S. businesses have added 13.2 million jobs over the last 67 months, the longest streak of private-sector job growth on record. We’re in the midst of a solid and sustainable expansion: our deficit is down by three-fourths, our households and businesses have reduced their leverage, and thanks to higher domestic energy production and investments in efficiency, we’re less reliant on energy imports to power our economy.

But the recovery elsewhere has not been as robust and overall global growth is too slow. Emerging markets that powered growth in the 2000s and immediately after the crisis are slowing. For China, this partly reflects the transition to a more sustainable growth pattern. Growth in Europe and Japan remains lackluster and unemployment – especially long-term and youth unemployment – remains far too high in many countries.

At the same time, in too many countries income inequality is rising, middle-class incomes are stagnating, and too many economies are falling short when it comes to creating economic opportunity for their citizens.

The economic, political, and social consequences of these trends are serious:

In particular, we are seeing a cycle of low growth and lack of opportunity. A growing body of evidence, including research from both the IMF and OECD, shows that low growth and lack of economic inclusion are mutually reinforcing. In particular, income inequality in many countries has risen to such an extent that it is bad for growth. These studies challenge the longstanding assumption that there is an inevitable tradeoff between equality and efficiency. In fact, the opposite is increasingly true: it is possible to design policies that both promote growth and increase opportunity for low- and middle-income families.

We are also seeing an erosion of political support for international economic integration. Lackluster growth and lack of opportunity is in some places fueling the rise of political parties that favor protectionism and isolation. The reality is that for people to support global integration and reforms that may be pro-growth overall, they need to see that these policies will lead to jobs and opportunities.

Further, we have seen bouts of financial market volatility. Low growth – especially when coupled with a heavy reliance on monetary and credit-oriented stimulus in a number of countries – has created the conditions for bursts of financial market volatility like we saw in August, and the interconnectedness of global markets means that shocks can be transmitted quickly.

Moreover, incomplete policy responses to low growth in a number of major economies is leading to a resurgence of global imbalances. This is one of the most worrying trends that the G-20 needs to focus on. The Netherlands, Germany, and Korea are on track to run external surpluses of nearly 10 percent, nearly 9 percent and over 7 percent of GDP, respectively. Surpluses of this magnitude are a sign that domestic demand in these economies is falling short.

What We Have Left To Do

I believe firmly that it is within the G-20’s capacity to tackle the shortfall in global demand, and I see four areas where more work needs to be done.

First, the G-20 must fully adopt the lessons of recent history and not withdraw fiscal support too hastily. This is a lesson we know well ourselves in the United States. We saw how weakness in state and local government finances became a drag on the economy once the Recovery Act’s temporary aid to states began to phase out. We also saw how sequestration damaged growth and job creation during the part of 2013 it was allowed to take effect, not to mention the shutdown and debt ceiling brinksmanship. This week, we took a major step in a better direction, as President Obama signed into law a budget agreement that will provide fiscal certainty – and considerable additional near-term fiscal support – over the remainder of his Presidency.

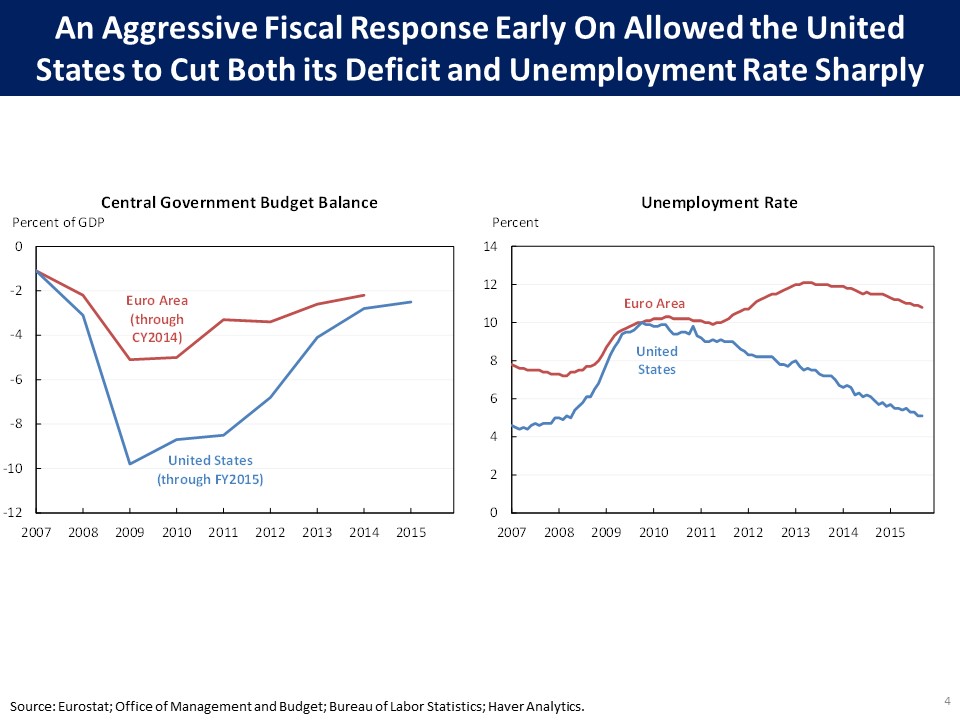

Overall, we have pursued a highly supportive fiscal course since 2009. In part as a result of this historic fiscal response combined with accommodative monetary policy, the United States has managed to cut its unemployment rate significantly, and spark the sort of solid and sustained recovery in which the deficit-to-GDP ratio has come down significantly as well.

The contrast between the United States and the Euro Area in this regard is instructive. In 2009, the United States and Euro Area saw their unemployment rates rise to comparable levels, but the United States’ budget deficit in relation to GDP was roughly twice as large as the combined deficits in the Euro Area member economies, reflecting the more aggressive fiscal policy response in the United States. Today, the deficit-to-GDP ratios are roughly comparable. But the unemployment rate in the United States is down to 5.1 percent, while the Euro Area unemployment rate is still in the double digits.

The Euro Area does not have a centralized fiscal policy aimed at macro-stabilization. As such, when some countries are growing well and see no need for fiscal support and others face concerns of confidence in sovereign debt markets, there can be a bias towards austerity. This is politically a hard nut to crack, but recognition of this bias could encourage greater efforts to overcome it.

On a similar note, in Japan, a failure to achieve sustained growth has worsened standard measures of fiscal sustainability. Since 2007, Japan’s gross government debt to GDP ratio has increased from 183 percent to 246 percent. During that period, nominal debt rose by about 3 percent per year – a pace that should not be unmanageable for an economy that is growing and generating a healthy level of inflation. The more fundamental challenge has been that nominal GDP has actually shrunk slightly over this time.

Second, in G-20 economies where interest rates are low and fiscal space exists, governments must do a better job of taking advantage to invest in the future. As the IMF noted last year, for some advanced economies, “Public infrastructure investment could pay for itself if done correctly.” The U.S. Congress will have yet another opportunity to take advantage of low interest rates when the latest short-term infrastructure re-authorization expires on November 20. President Obama’s domestic team will be working hard to secure a long-term deal that provides certainty, boosts near-term demand, and raises long-run potential.

Low interest rates also make infrastructure investment particularly attractive in Europe. For instance, the IMF has called for Germany to boost infrastructure investment by approximately 2 percent of GDP over four years. An infrastructure investment program would help Germany absorb some of the recent influx of labor resources and insure against further weakening in external demand—and both of these positive effects would come at a very low cost given current borrowing costs.

Prior to the crisis, the traditional worry was over whether monetary policymakers had sufficient independence to mitigate the effects of profligate fiscal policymakers, who were biased toward inflationary over-spending. In the years following the crisis, the opposite has been true: the insufficient fiscal policy response and inclination towards fiscal austerity in a number of economies has left monetary policymakers to carry an unusually heavy burden in lifting too-low inflation up closer to healthy levels. Of course, excessive reliance on monetary policy may not succeed, and it can have implications for financial stability and external balances. That is why we have constantly emphasized the importance in the G-20 of using all available policy tools.

Third, boosting final demand around the world will require steps to make growth more inclusive and strengthen the middle class. In a world where demand is persistently weak, it is critical to put more money in the pockets of middle-class households so they can spend and drive growth. And when overall potential growth is slowing, it is also essential to invest in education and training, so that all our citizens – especially youth, which has been a focus of the Turkish Presidency – have the opportunity to realize their full individual potential. On a similar note, the G-20 economies should also take action to incentivize labor force participation, including moving rapidly towards the goal of narrowing their respective gaps between female and male labor force participation by a quarter by 2025.

When it comes to the specific policy proposals to achieve inclusive growth, there is no one-size-fits-all prescription for the G-20. In the United States, President Obama has recognized the magnitude of the challenge we face when it comes to boosting middle-class incomes. In fact, President Obama has said that the combination of rising inequality and declining mobility is the defining challenge of our time. It’s a challenge that has been decades in the making, and one that won’t be solved overnight, but this Administration has taken some major steps to chart a more inclusive course for the future – steps that we have come to refer to as our “middle class economics” agenda. We expanded health insurance coverage to more than 16 million people, made college education more affordable, and cut taxes for the middle class. This year, President Obama took a step to expand overtime protections for 5 million workers. And he will continue to fight for an increase in the minimum wage, a permanent extension of key low- and middle-income tax credits, additional investments in education from pre-school to community college, and greater workplace flexibility and access to paid leave.

The President has also made the expansion of free trade agreements a top priority. These are trade agreements based on high standards, such as the recently concluded Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership under negotiation. These agreements are a crucial chance to shape the rules of trade, while expanding economic opportunity for the middle class. Through TPP we are showing that it is possible to make commitments to protecting labor rights and fighting to eliminate nefarious practices like child and forced labor.

The link between strengthening the middle class and supporting overall growth is particularly clear for China – and as the world’s second largest economy, China’s capacity to make progress on this will be critical for the future of the global economy. China has recognized that an export-driven strategy is no longer sustainable for an economy of China’s size. China’s leadership recognizes this. In September, President Xi emphasized that China “will not lower the renminbi exchange rate to stimulate exports” and that China is “moving from an export-driven and investment-driven economy into an economy driven by expanded consumption and domestic demand.” China could grow its emerging middle class, boost global demand, and advance its medium-term rebalancing objectives by relying more heavily on pro-consumption fiscal policy to tackle slowing growth. While the People’s Bank of China has now cut interest rates six times in the past year, China may be reaching the point where credit-oriented stimulus is yielding diminishing returns. We continue to encourage China’s leadership to look at other options, like consumer-oriented tax cuts, as well as accelerating dividends from state-owned enterprises to pay for a more robust social safety net and for extending urban social services to migrants from the provinces. Some policies along these lines were referenced in the recently concluded Fifth Plenum. Through the next five year plan, China’s leadership has an opportunity to solidify the path of reform.

Turning briefly to Europe, Ben Bernanke and others have called for policies that will support stronger wage growth in Germany. The introduction of a minimum wage this year was a positive step that will allow German workers to share further in the benefits from growth. We would welcome additional wage increases for German workers, in line with Germany’s productivity growth, as well as cuts to the consumption taxes they pay. This will better position Germany to do more to contribute to global demand.

Fourth, G-20 countries should take steps to unleash greater private investment. In many places, steps to generate a stronger, more sustained recovery in final demand will help lift business sentiment and create greater certainty about future economic prospects. In other places, deep reforms are needed to improve the business climate and allocation of credit and to open to foreign investment. This is particularly critical for emerging market economies where policy space is more constrained. Recognizing the crucial need to mobilize private investment, the G-20 last year launched the Global Infrastructure Hub, which will help in part to match investors with projects. This year, the G-20 has worked closely with the business community to improve the enabling environment for investment.

There are a number of hypotheses about why private investment has been weak and why there appears to be a global excess of savings. The G-20 will continue to consider these hypotheses, but in many cases, the answers are still the same: encourage private investment, make sure public investment plays the crucial role it should, use infrastructure investment to raise productivity, and support demand. If we do these things effectively, concerns about persistently low potential output growth will not become self-fulfilling prophecies.

The Role of the G-20 and China’s G-20 Presidency in 2016

To conclude, I would like to say a word about the role of the G-20 and the exciting prospet of China’s G-20 Presidency in 2016. The history of the G-20 speaks to the power of leaders working together to address even the most daunting challenges.

From green growth and sustainability, to deficiencies in cross border financial market regulation, to women’s labor force participation, the G-20 has a strong track record of forcing a conversation on the core challenges we face. So as the world grapples with the consequences of low growth and lack of opportunity and inclusiveness, the G-20 will help to ensure that these issues get the attention they deserve.

Looking ahead to China’s Presidency in 2016, I have no doubt that my Chinese counterparts will develop a robust and ambitious agenda. During President Xi’s state visit in September, the United States expressed its strong support for China’s G-20 presidency. The joint economic fact sheet set out a number of areas for cooperation in the G-20 next year, including environmental standards for infrastructure lending and global health security.

My hope above all is that when leaders arrive in China next year, they can say they have acted decisively to tackle the shortfall in global demand. Tackling the challenge of low growth may seem highly difficult, especially since it is less acute, but history suggests that the G-20 is up to the challenge. In 2009, the G-20 faced the specter of a repeat of the Great Depression and a retreat to protectionist policies. I would argue that we rose to meet those challenges. Moving to robust and inclusive global growth that expands our economies from the middle out may be just as difficult. But the imperative to work together to do so is just as great.