Remarks for Senior Advisor Brian Deese – As Prepared for Delivery

Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy

October 11, 2016

It’s a pleasure to be here at Columbia and a unique time to talk about climate and energy policy. Abroad, we are writing a new chapter in international climate diplomacy, and at home we are witnessing an historic transformation of our energy sector. In that context, I want to offer a few impressions I have had working on these issues for President Obama, and offer some thoughts about the path ahead.

1. The decoupling of emissions and economic growth is an historic shift for the US

The first impression is that a lot changes once it is possible to reduce dangerous carbon emissions while growing our economy.

Since the industrial revolution, it has been a tenet of mainstream economics that GDP and carbon emissions grew together. While that growth lifted much of the world out of poverty, it created a structural reliance on carbon-based energy systems that harmed public health and the climate.

The perceived linkage between affordable energy and carbon emissions also defined the politics of climate change. It’s hard to convince people to accept a lower standard of living for almost anything, let alone something like climate change that, by its nature, is slow moving and diffuse.

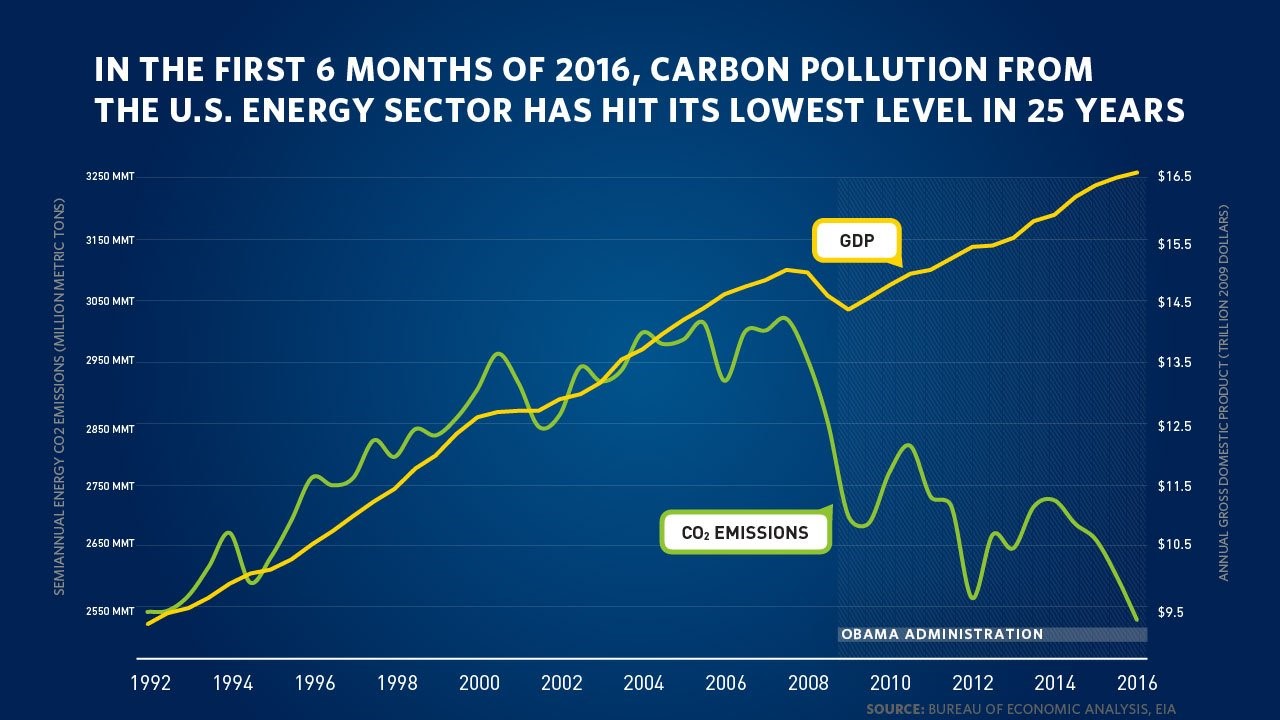

But that has now changed. Since 2010, U.S. GDP grew by 11 percent, while energy sector emissions fell by 6 percent.

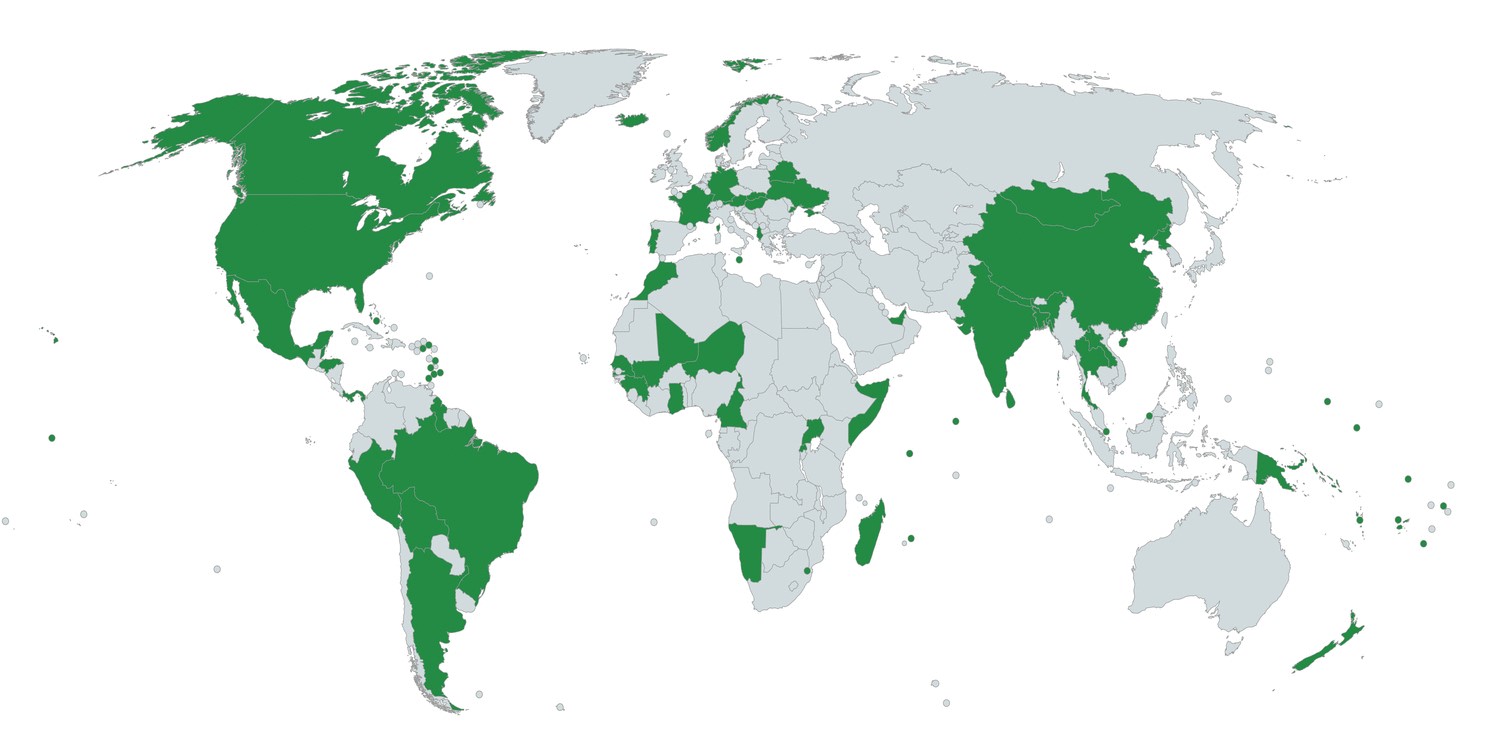

And it’s not just the United States. More than 20 countries have seen growth and emissions decoupled, including some like Bulgaria and Uzbekistan whose industrial sectors are still expanding as a share of their economies. Other studies have even suggested that China – whose stated growth in 2015 was 6.9% – may be close to peaking its emissions.

And it’s not just the United States. More than 20 countries have seen growth and emissions decoupled, including some like Bulgaria and Uzbekistan whose industrial sectors are still expanding as a share of their economies. Other studies have even suggested that China – whose stated growth in 2015 was 6.9% – may be close to peaking its emissions.

Globally, over the most recent two years with data, the economy has increased by 6.7 percent while energy sector emissions have stayed flat.

Breaking this linkage is economically significant, and politically important. Our successes in reducing emissions over the last several years have not been about sacrifice – or about trading off prosperity today for some future benefit. It has been about innovation, jobs and contributing to the longest streak of total job growth on record.

In fact, this period of decoupling allows us to say more unambiguously than ever that acting to combat climate change is in our best economic interest. Period. Without action, we risk exposing our economy to trillions of dollars in avoidable damages. Why would we take these economic risks when we have solutions to grow our economy and reduce emissions at the same time?

This is not to say that the transition to lower emissions growth is free from disruptions. That is why for several years, President Obama has called for an aggressive effort to help coal communities and workers through this market transition. There has been some movement in Congress on these efforts but not enough – passing these measures should be a priority when Congress gets back to work this fall.

2. Emission projections demonstrate that policy can make a real difference

Now, it is hard to argue that this decoupling is insignificant. But what if it is an accident of history? Here, the argument goes that emissions initially fell because of the recession; when economic growth picked up, we happened across a revolution in shale gas and, voila, emissions continued to fall.

But my second impression is that accidents of history are rare. Breaking the link between growth and emissions has required sustained policies over time.

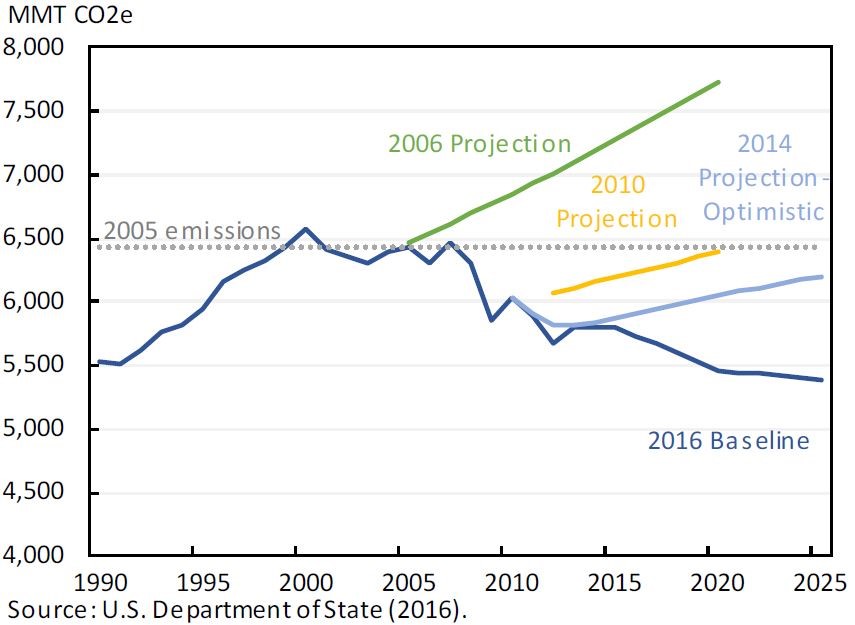

In 2010, emissions were projected to grow indefinitely for the next decade. In 2014, our projections showed the same – though the growth looked to be slowing. But by 2016, our projections showed absolute reductions in emissions – consistent with our goal of reducing emissions 17% below 2005 levels by 2020.

What explains this change? Shifting from coal to natural gas is part of the picture. But the story is increasingly a result of policy.

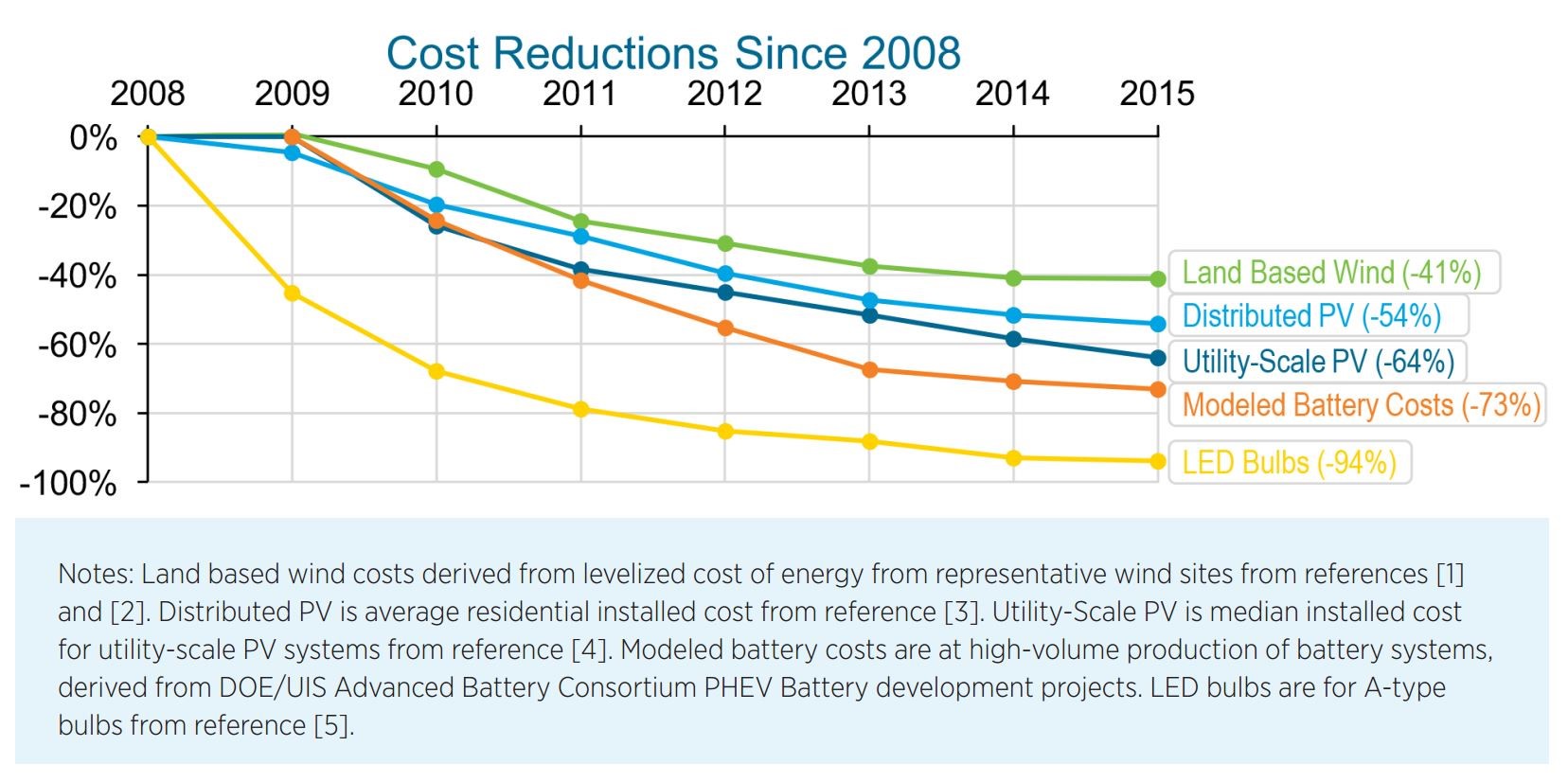

In the electricity sector – our largest emitter of carbon dioxide – the levelized cost of energy has dropped significantly since 2008: 41 percent for wind, 54 percent for distributed photovoltaic installations, and 64 percent for utility scale solar. These cost reductions were driven, in part, due to investments we made through the Recovery Act, including the tax credits for wind and solar that were extended again last year. When the Clean Power Plan takes effect, it will provide regulatory incentives to continue these market trends.

In the electricity sector – our largest emitter of carbon dioxide – the levelized cost of energy has dropped significantly since 2008: 41 percent for wind, 54 percent for distributed photovoltaic installations, and 64 percent for utility scale solar. These cost reductions were driven, in part, due to investments we made through the Recovery Act, including the tax credits for wind and solar that were extended again last year. When the Clean Power Plan takes effect, it will provide regulatory incentives to continue these market trends.

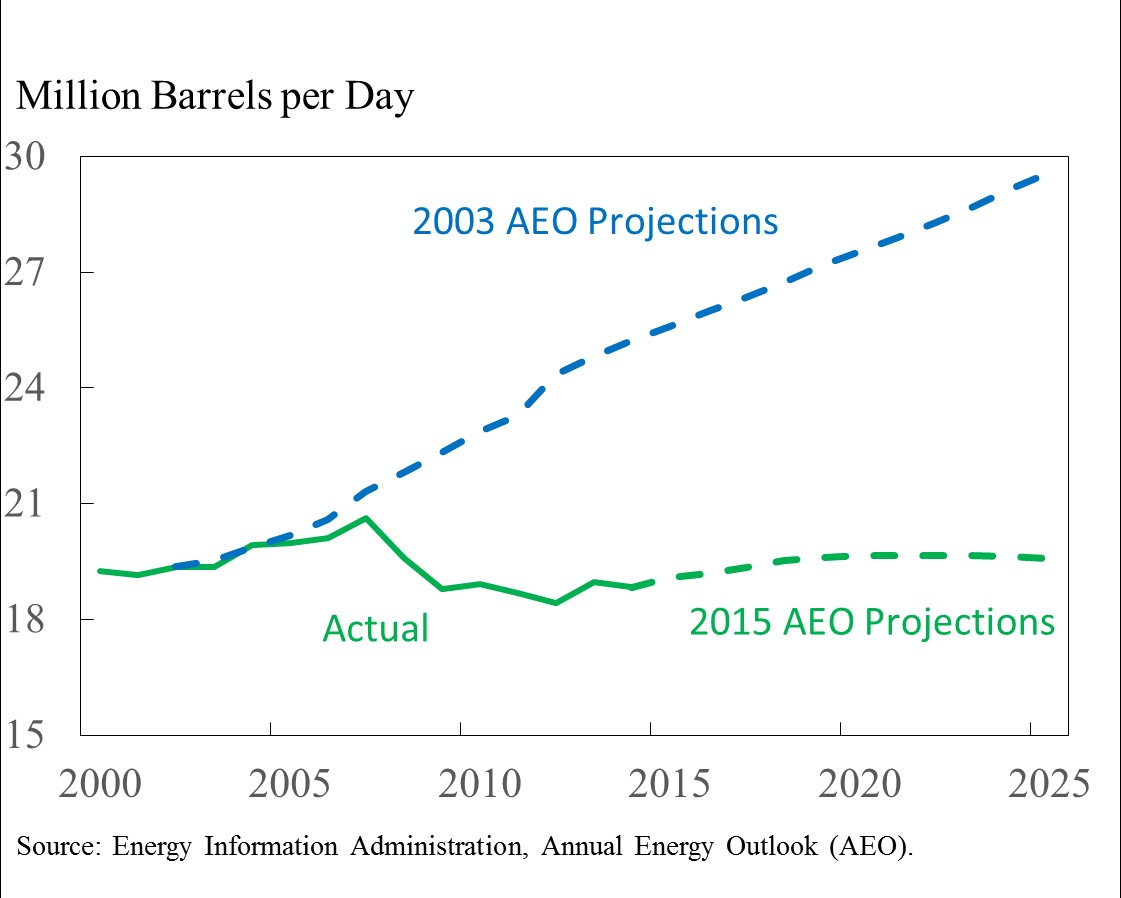

In the transportation sector – our second largest emitting sector – petroleum consumption in 2015 was 2 percent lower than in 2008. We use less oil even though our economy has grown more than 10 percent. Few predicted this would happen. Indeed, petroleum use in 2014 was more than 25 percent below 2003 projections, and projected use in 2025 is now 34 percent lower than those prior projections.

A principal reason for this surprising outcome is that, for the first time in decades, the President updated fuel economy standards for our nation’s passenger vehicles and implemented the first-ever fuel economy standards for medium- and heavy-duty trucks.

The same dynamic is at play in the industrial, and commercial and residential sectors – our third and fourth largest sectors – where energy consumption today is holding flat despite a larger economy. Again, this is not a spontaneous phenomenon but one that results, in part, from government efforts. For example, since 2009 the Department of Energy has issued 42 new or updated energy efficiency standards for everything from your air conditioners and refrigerators to your ceiling fans and washing machines. Recovery Act Investments jumpstarted smart metering and smart markets that allow homes and businesses to sell billions in energy savings back to the grid. And the Administration has set a goal and put in place policies to reduce methane emissions 40-45 percent from 2012 levels by 2025.

3. Even "second best” policy approaches can be well worth it

Now, our policy approach isn’t perfect. In fact, if you were starting from scratch you would not arrive here. And of course, theory suggests a nationwide price on carbon would lead to even more economically efficient outcomes.

But it’s important to take very seriously the first best nature of a second best policy framework.

When you look at the modeling under an economy-wide carbon price, the vast majority of initial reductions come from the power sector. And because the Clean Power Plan relies on well-established Clean Air Act authority to put in place a market-based, flexible approach to reduce emissions in the power sector, much of the initial emissions reductions we achieve will closely mirror the initial emission reductions under an economy-wide approach.

And in a political environment where the prospects of a de novo national carbon pricing mechanism passing Congress are remote, optimizing the market based approaches across sectors will increasingly be the best case solution for policy makers.

4. Domestic success is paying increasing international dividends

This second best policy approach has also enabled the United States to become a global climate leader.

Our domestic leadership in reducing emissions provided the credibility to form an historic partnership with China, and encourage ambition by countless other countries in Paris. The Paris Agreement itself is a triumph of second best alternatives – instead of a top-down global pricing system, Paris relied on nationally determined ambition and, in doing so, created a new formula for global action.

One of the key questions coming out of Paris was whether that approach would pay dividends. Was it a flash in the pan or the foundation on which momentum could beget momentum going forward?

While I did not plan this timing, the answer is emerging as I speak:

Entry into Force. First, last week, we crossed the threshold needed for the Paris Agreement to enter into force. Shortly after the Agreement was adopted, there was a serious discussion about how soon this should happen. Some argued it would be prudent to push for entry into force well before 2020 to encourage global climate momentum. Others thought there was value in moving slower, to allow certain provisions of the Agreement to be revisited. But virtually no one thought it was possible for the Agreement to enter into force this year.

In the days following Paris, President Obama spoke by phone with President Xi and with Prime Minister Modi. They discussed the idea of the Agreement entering into force this year. President Obama left those conversations convinced that, with leadership from the major emitters, what seemed improbable was indeed possible, and entry into force in 2016 was an audacious goal worth pursuing.

The process over the past nine months has been challenging; it required overcoming doubters and urging ambition. But the result is an important sign of U.S. climate leadership and growing momentum after Paris.

Aviation Emissions. Second, and also last week, more than 190 countries agreed to cap net emissions from international aviation, under a system where airlines will have to reduce emissions or purchase carbon offsets for any emissions above the cap.

This fills a gap left by the Paris Agreement. International aviation represents only 2 percent of global emissions today, but the sector is forecasted to grow 5 percent each year beyond 2020, posing a threat to Paris’ temperature goals.

A year ago, few thought addressing international aviation emissions was possible. Unlike Paris, a viable solution here requires a global market based mechanism. But countries were willing to get creative with a staged approach that reflects countries' different capacities. And already, countries representing 85 percent of air traffic have stepped up to voluntarily participate early – countries from Guatemala to Kenya, China to the U.S.

By doing so, the world has established a compelling blueprint for reducing emissions in a market-based manner for highly integrated and high emitting sectors in our globalized economy.

Montreal Protocol. Third, this week in Kigali, we are negotiating an amendment to the Montreal Protocol to phase down the use of the super polluting substance known as hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs. An ambitious amendment to the Montreal Protocol could avoid up to 0.5°C of warming by the end of the century. It would be the most important step the international community could take to make good on Paris's promise.

The verdict is still out on this one, and it’s one reason I need to get back to DC.

But already more than 100 countries have called for an ambitious amendment with an early freeze date. And donor countries and philanthropies have made the single biggest contribution of financing for energy efficiency in this sector. So I remain optimistic about what we can achieve this week.

5. The path forward

In summary: decoupling is here to stay; it's not an accident of history; and while our policy architecture is inherently second-best, it is paying real dividends, which have only increased internationally since Paris.

So where do we go from here?

Optimizing and harmonizing sector-by sector approaches. First, more attention must be paid to optimizing and harmonizing the sector-by-sector approach to reducing emissions. This means making it easy and attractive to adopt market based regulatory approaches and encouraging trading wherever feasible – something the EPA is very focused on. It means aligning implied carbon prices between sectors as the next generation of fuel economy standards, energy efficiency regulations, and power sector reforms are contemplated. It means working more closely with Canada, Mexico and other partners on regional markets. And it means improving private sector climate disclosure practices so investors can allocate private capital more efficiently.

Of course, this doesn't mean abandoning a potential economy-wide solution. But given the moment we’re in, we will need more work and brainpower – including from centers like this one – on how to make the second best architecture more effective in the future.

Linking Climate and Conservation. Second, we’ll need to put much more focus on the least discussed component of our climate strategy – land conservation. If the policy architecture I just described holds, then squeezing additional reductions out of a largely decarbonized power sector will become increasingly difficult. As a result, we will need to bolster the forests, agricultural lands, and urban areas that are likely to remain our most effective carbon capture and sequestration mechanism.

This will require fundamentally rethinking policy. While we’ve improved our measurement of sinks, invested in research that promotes climate-smart land management and agriculture, and developed new business models for conservation, we need to do more. We need to find ways to implement pay-for-practice incentives so that negative emissions become one of the many commodities our farmers and foresters can generate. We need to think bigger about reforesting. And we need to ensure we’re using U.S. lands as efficiently as possible: promoting smart growth instead of suburban sprawl, using agricultural subsidies to incentivize efficient practices, and supporting innovative strategies, like precision agriculture to support low-carbon bioenergy crops. If we get this right, it could lead to some of the most efficient emissions reductions in our economy.

Taking climate resilience as seriously as climate mitigation. Third, we can’t ignore what is happening all around us – even as we accelerate our mitigation efforts. This weekend, we watched in horror the devastation that Hurricane Matthew caused in the Caribbean and then Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. We know that the frequency and severity of natural disasters like hurricanes and droughts are increasing rapidly and we will deal with serious impacts even if we constrain temperature increases to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius. This Administration has strengthened our resilience to climate change – through efforts like implementing a federal flood risk standard – but we need to do more. We must apply science-based information, technology and tools to address climate risk. We must embed climate resilience into federal agency and private sector missions and operations, and move away from paying after disaster strikes to rewarding resilience efforts before the storm hits. And we must approach flood insurance and other federal programs like the major insurance companies do – by recognizing that 100 year floods are happening more frequently and we must account for practices that expose the federal balance sheet to greater risk.

International leadership and ambition. My last point is that we must believe in the proposition that momentum, speed and ambition are possible on the global stage. Just as entry into force of the Paris Agreement went from an impossibility to an inevitability this year, we must set our sights higher, be more audacious, and then make good on those aspirations.

In short order, that means building out Paris's essential reporting and review requirements into a system that is transparent, uniform and independently verifiable. It means encouraging other countries to pursue steadily more ambitious nationally determined targets – not just in the next 5 year cycles but now. Only six months after Paris, we announced a North American Climate, Clean Energy and Environment Partnership and upped our goal for clean energy across the continent. We need more collective action like this – so countries can see that faster and more ambitious action is possible, with the necessary support. And it means filling gaps in Paris’ bottom-up framework: applying the model we agreed to for aviation last week to other sectors, phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and export finance for high polluting projects, and radically scaling up clean energy R&D and green finance, in part by focusing on the effective management of partnerships like Mission Innovation and the Green Climate Fund.

6. Conclusion

That is a full plate, but it underscores that this is an exciting time to care about and work on climate policy. Of course it’s a little scary too. The President was asked last week to give a grade to our global efforts to combat climate change. He gave us an “incomplete.” The problem is accelerating and the science is increasingly clear. But internationally and domestically, we’ve begun to put in the place the frameworks necessary to conquer this challenge. And as we come to the end of this Administration, that’s worth noting. Briefly. Before we get back to work.