Fourth-quarter economic growth was revised up and domestic demand continued to grow. Overall, the most stable and persistent components of output—consumption and fixed investment—rose a solid 2.7 percent over the four quarters of 2015. Weaker foreign growth continued to weigh on domestic output in the fourth quarter, underscoring the importance of policies that open our exports to new markets while promoting strong domestic demand. There is more work to do, and the President is committed to policies that will boost our long-run growth, including high-standards free trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and raising the minimum wage.

FIVE KEY POINTS IN TODAY'S REPORT FROM THE BUREAU OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS (BEA)

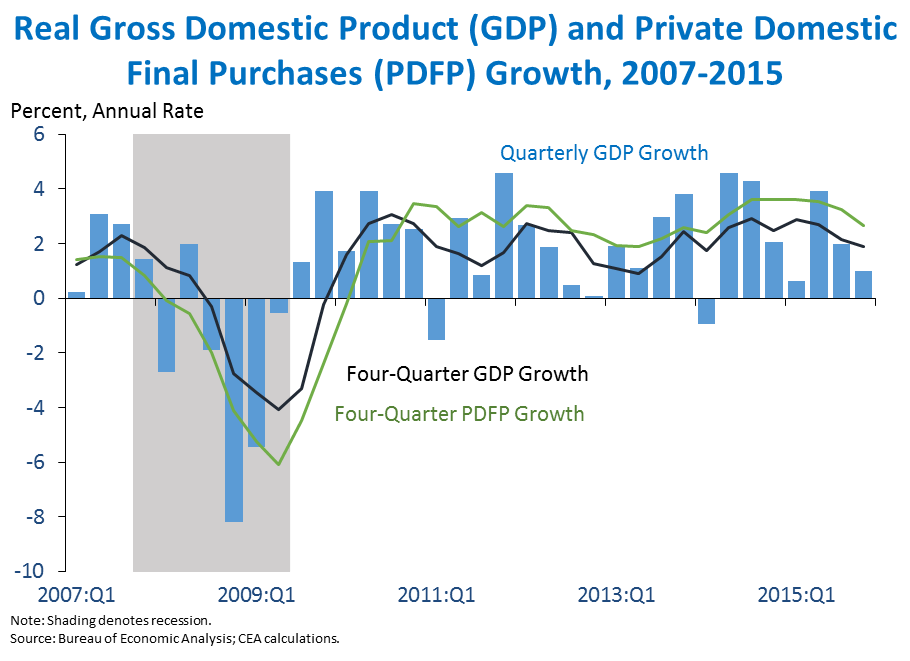

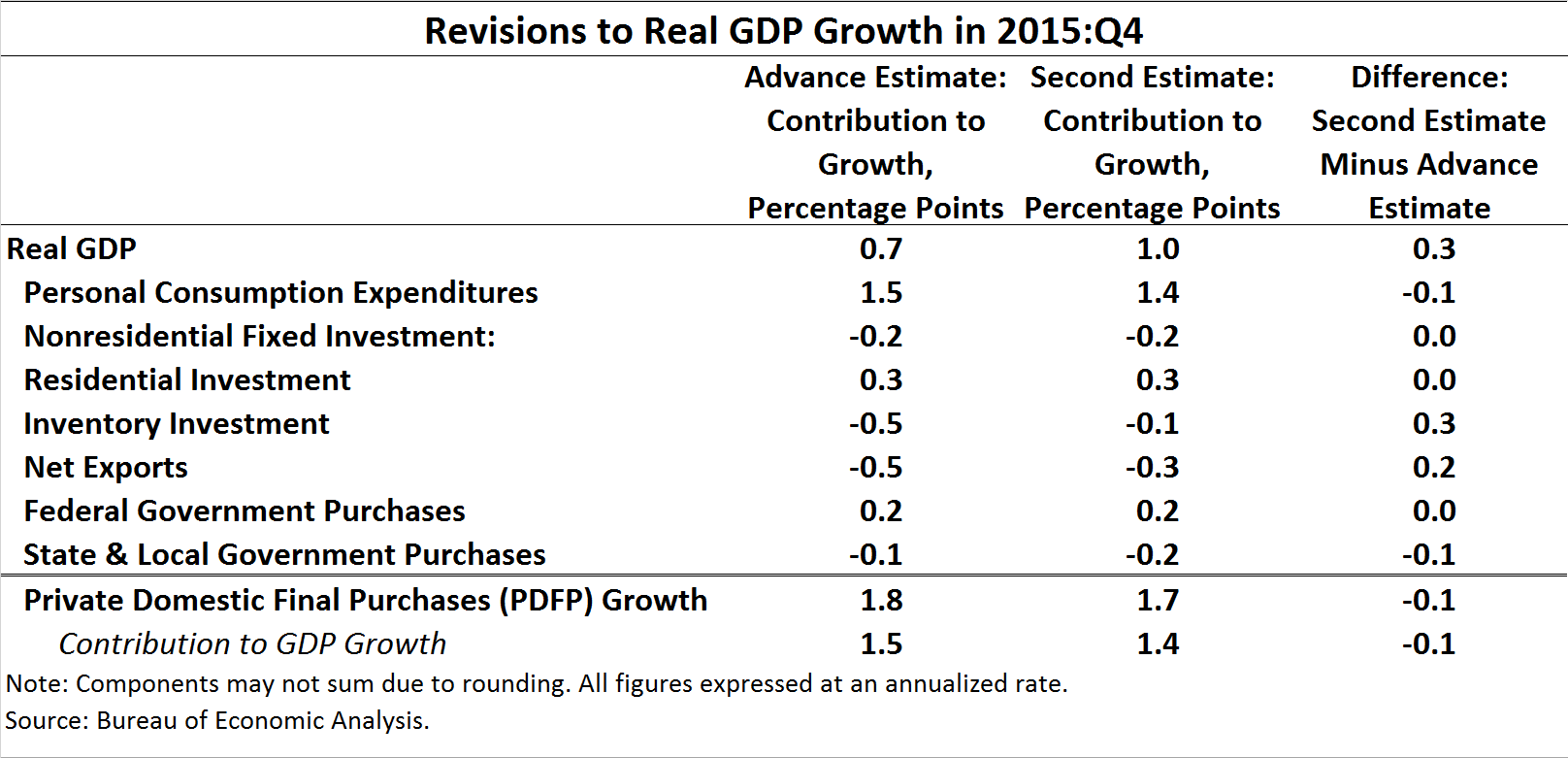

1. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rose 1.0 percent at an annual rate in the fourth quarter, according to BEA’s second estimate. Real GDP grew more than originally estimated largely due to an upward revision to inventory investment. Consumer spending rose a solid 2.0 percent in the fourth quarter, but below the robust 3.0-percent pace in the third quarter. The outlook for consumers remains favorable and some of the fourth-quarter slowing was due to unseasonably warm weather that temporarily reduced real spending on utilities. In contrast, investment in structures declined 6.6 percent in the fourth quarter, as the low level of oil prices has led again to a sharp contraction in oil-related investment. Investment in equipment declined 1.8 percent in the fourth quarter, likely related to slower global demand as well as some tightening in corporate credit markets. During the four quarters of 2015, private domestic final purchases (PDFP), an aggregate of consumption and fixed investment, grew solidly, even as the U.S. economy faced headwinds from abroad (see point 5 below).

2. Fourth-quarter annualized real GDP growth was revised up 0.3 percentage point. The upward revision to GDP growth was fully accounted for by a smaller decline in inventory investment than originally estimated, with smaller offsetting revisions in net exports, personal consumption, and State and local government purchases. In the second estimate, inventory investment subtracted 0.1 percentage point from fourth-quarter GDP growth after subtracting 0.7 percentage point in the third quarter. As discussed in an earlier CEA blog post, quarterly changes in inventory investment are volatile and, on their own, are poor predictors of future GDP growth. Nonetheless, the supply of manufacturing and trade inventories remained elevated in December despite the recent declines in inventory investment, suggesting the possibility of further declines in 2016.

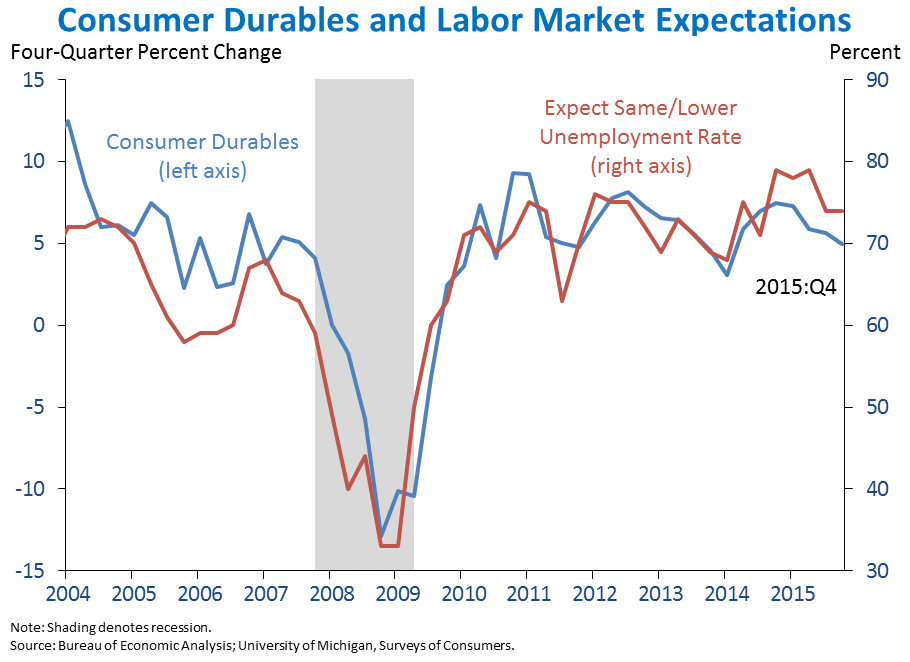

3. Consumer spending on durable goods continued to rise strongly as households remained upbeat about the labor market. Real outlays on consumer durables rose 3.4 percent in the fourth quarter, well above the 2.0-percent growth in total consumer spending. In fact, durable goods spending, which tends to be highly sensitive to changes in both actual and expected income, has risen strongly throughout the recovery. Robust growth in real disposable income, partly due to steep declines in oil prices (see point 4 below), has boosted spending growth since mid-2014. In addition, consumer spending remains a bright spot in the U.S. economy due to the ongoing labor market recovery. Over 2015, the economy added 2.7 million jobs, completing the strongest two years of job growth since 1999. Consumers are also upbeat about the labor market going forward, which has likely been a particular support to durable goods spending. According the Michigan Surveys of Consumers, in the fourth quarter nearly three-quarters of individuals said that they expect the unemployment rate to hold steady or decline further. Expectations for the labor market remain upbeat despite a modest decline in optimism in the second half of 2015.

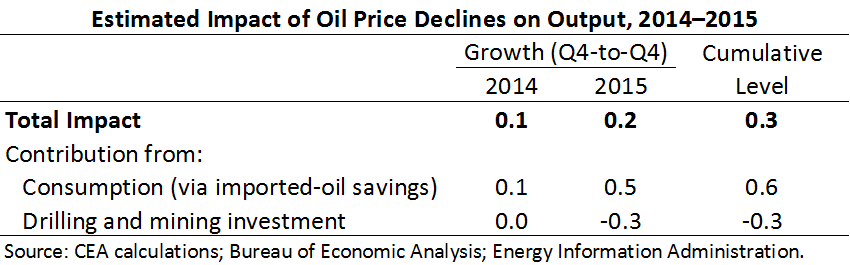

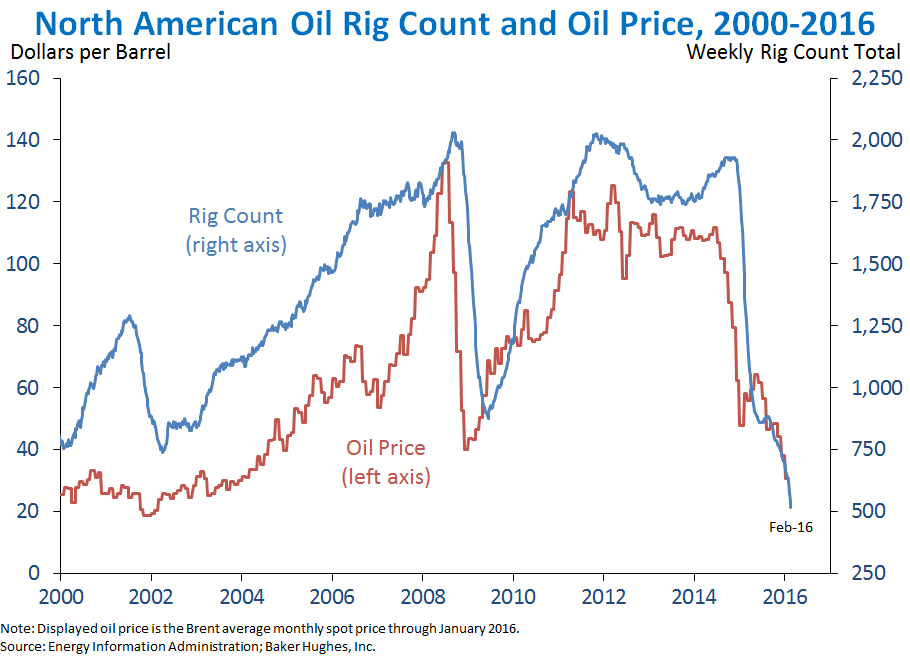

4. CEA estimates that low oil prices provided a small direct boost to real GDP growth in 2015, as the substantial benefits to consumers narrowly outweighed the sharp pullback in investment among energy producers. The price of Brent crude oil was $37 per barrel at the end of 2015, two-thirds lower than its recent peak in June 2014. The increase in global oil supply was a key factor pushing down oil prices, though the slowdown in global growth (see point 5 below) also contributed. As discussed in Chapter 2 of the 2016 Economic Report of the President, falling oil prices affect the U.S. economy through many channels (such as lower costs to consumers and to transportation industries, as well as reductions in oil-related investment), and the overall impact on GDP is difficult to precisely quantify. CEA estimates that the decline in oil prices directly boosted real GDP growth by 0.2 percentage point during 2015, though the full impact may have been higher or lower due to indirect effects not incorporated into this estimate.

Because the United States is a net importer of oil, the decline in oil prices boosted real income and consumption. This positive impact—adding around 0.5 percentage point to GDP growth during 2015—was somewhat less than the impact of oil price declines in the past because U.S. net oil imports have fallen as domestic oil production has risen. However, the positive impact on consumption was partially offset by a sharp drop in oil drilling and exploration. This reduction in investment subtracted 0.3 percentage point from GDP growth during 2015.

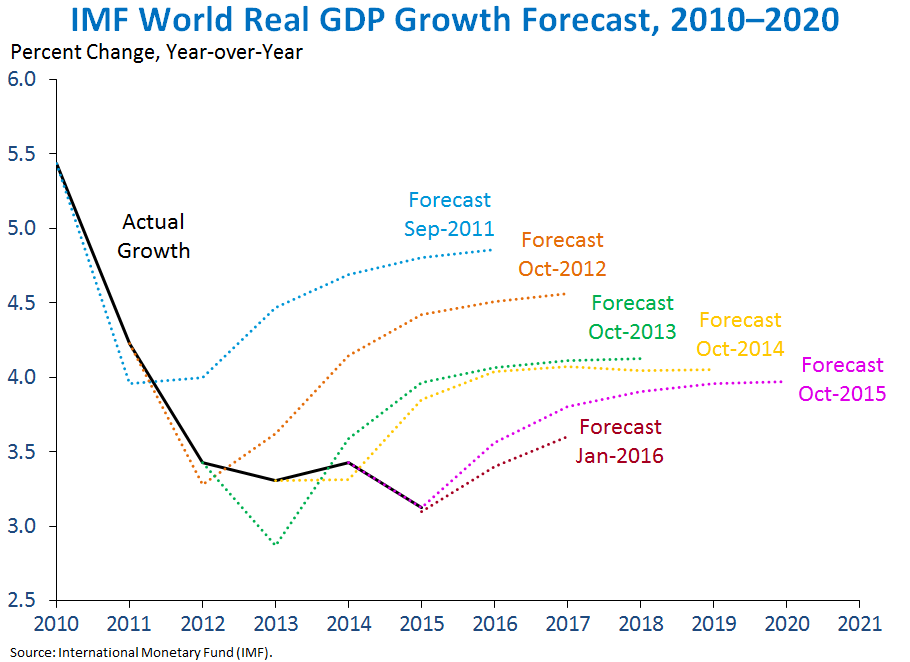

5. Net exports subtracted 0.6 percentage point from GDP growth over the four quarters of 2015, reflecting continued headwinds from slowing foreign growth. Real exports fell 0.8 percent during the four quarters of 2015, weighed down in large part by the slowdown in global growth. Over the last five years, global growth has consistently underperformed relative to forecasts. In January 2016, the International Monetary Fund estimated that global real GDP grew 3.1 percent on a year-over-year basis in 2015, below both the growth rate in the last three years and the pre-crisis average of between 4 and 5 percent.

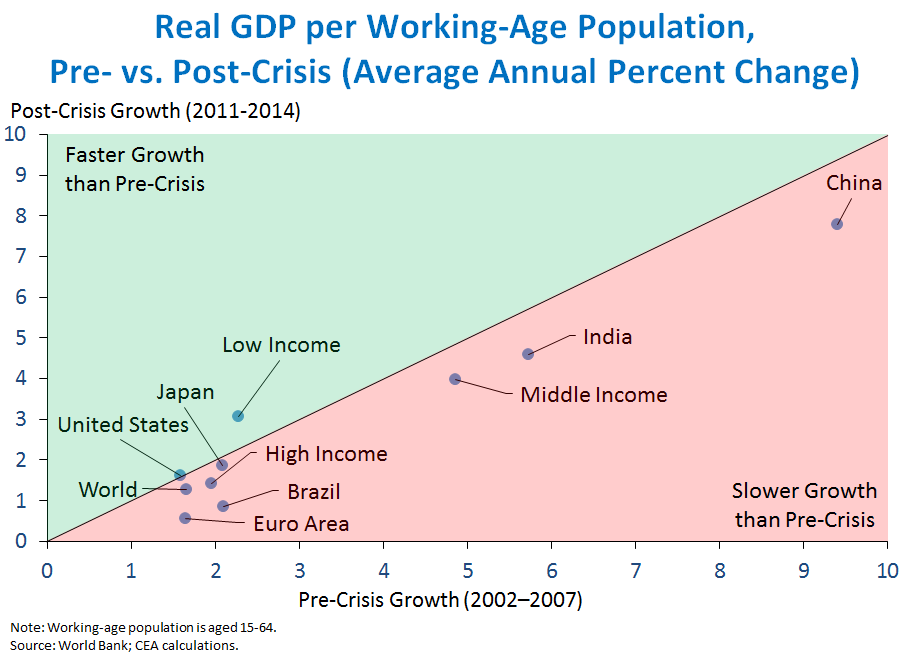

Growth has fallen short of expectations in both advanced and emerging-market economies. The chart below compares the growth of GDP per working-age population from 2011 to 2014 relative to 2002 to 2007, with points on the 45-degree line representing unchanged growth rates between these two periods. In general, the United States and Japan are growing at similar rates compared with their growth before the financial crisis after adjusting for changes to working-age population. On the other hand, the euro area has slowed relative to pre-crisis rates of growth, and some large emerging markets have also seen slower growth in recent years than before the crisis. The sensitivity of U.S. exports to foreign demand—especially in an environment where foreign demand is slowing—underscores the importance of reducing trade barriers and opening foreign markets to our exports. Read more about the global economic situation and its effects on the U.S. economy in Chapter 3 of the 2016 Economic Report of the President.

As the Administration stresses every quarter, GDP figures can be volatile and are subject to substantial revision. Therefore, it is important not to read too much into any single report, and it is informative to consider each report in the context of other data as they become available.

Jay Shambaugh is a Member of the Council of Economic Advisers.