Fourth-quarter economic growth was revised up 0.4 percentage point to 1.4 percent at an annual rate and domestic demand continued to grow. Overall, the most stable and persistent components of output—consumption and fixed investment—rose a solid 2.8 percent during the four quarters of 2015, well above the 2.0-percent GDP growth in 2015. Weaker foreign growth continued to weigh on economic growth in the fourth quarter, underscoring the importance of policies that open our exports to new markets and promote strong domestic demand. There is more work to do, and the President is committed to policies that will boost our long-run growth and living standards, including policies to support innovation and investments in infrastructure and job training.

FIVE KEY POINTS IN TODAY'S REPORT FROM THE BUREAU OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS (BEA)

1. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rose 1.4 percent at an annual rate in the fourth quarter, according to BEA’s third estimate. Fourth-quarter GDP growth was boosted by consumer spending (which rose 2.4 percent at an annual rate) and residential investment (which rose 10.1 percent at an annual rate). In contrast, investment in structures declined 5.1 percent, as low oil prices have led to a sharp contraction in oil-related investment. Investment in equipment and in inventories subtracted a combined 0.3 percentage point from GDP growth. Slowing global demand remains the key drag on real GDP growth, with real exports subtracting 0.3 percentage point from GDP growth in the fourth quarter. Overall, real GDP rose 2.0 percent during the four quarters of 2015, reflecting continued domestic strength despite substantial headwinds from abroad.

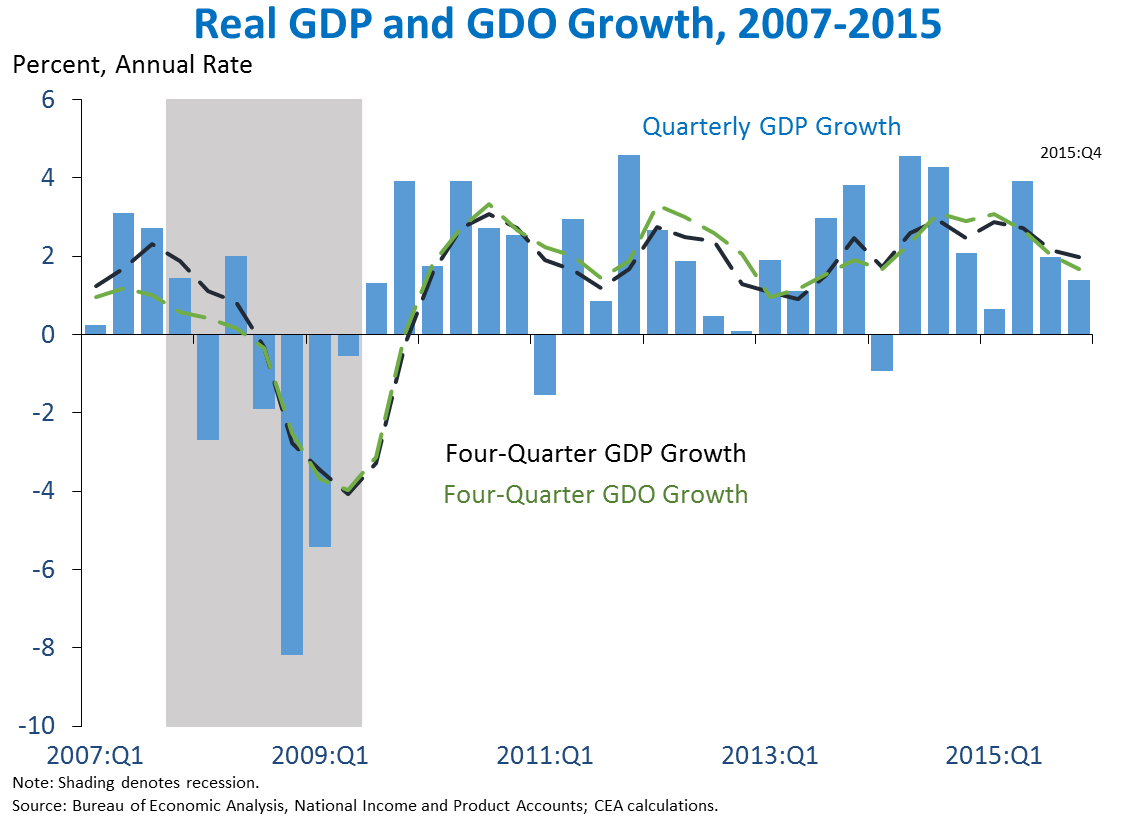

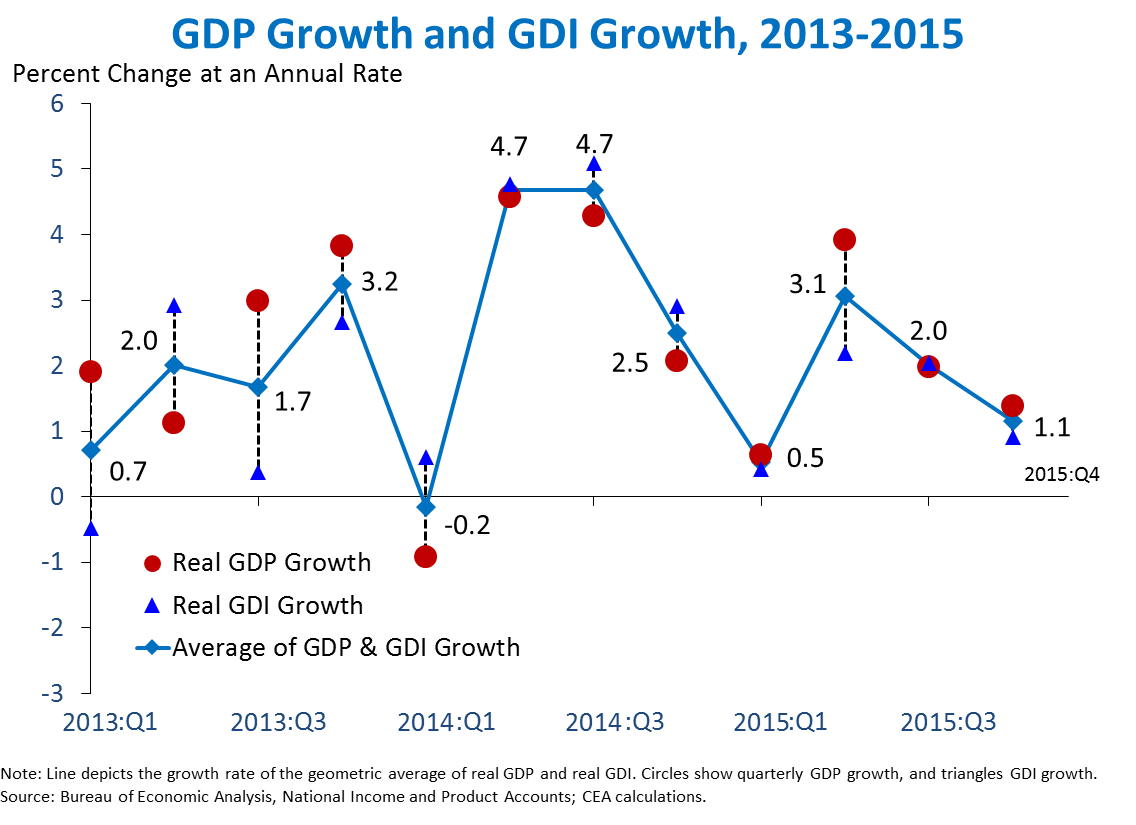

Real Gross Domestic Income (GDI)—an income-based measure of output—grew 0.9 percent at an annual rate in the fourth quarter, below the 1.4-percent increase in GDP—an expenditure-based measure of output. (In theory, these measures should be equal, but in practice often differ because they use different data sources and methods.) Real GDI growth was weighed down by a decline in corporate profits, which offset part of the solid growth in compensation of employees (see key point 3 below). The average of GDP and GDI, which CEA refers to as Gross Domestic Output (GDO), increased 1.1 percent at an annual rate in the fourth quarter and 1.7 percent during the four quarters of 2015. CEA research suggests that GDO is potentially a better measure of economic activity than GDP (though not typically stronger or weaker) over the long term.

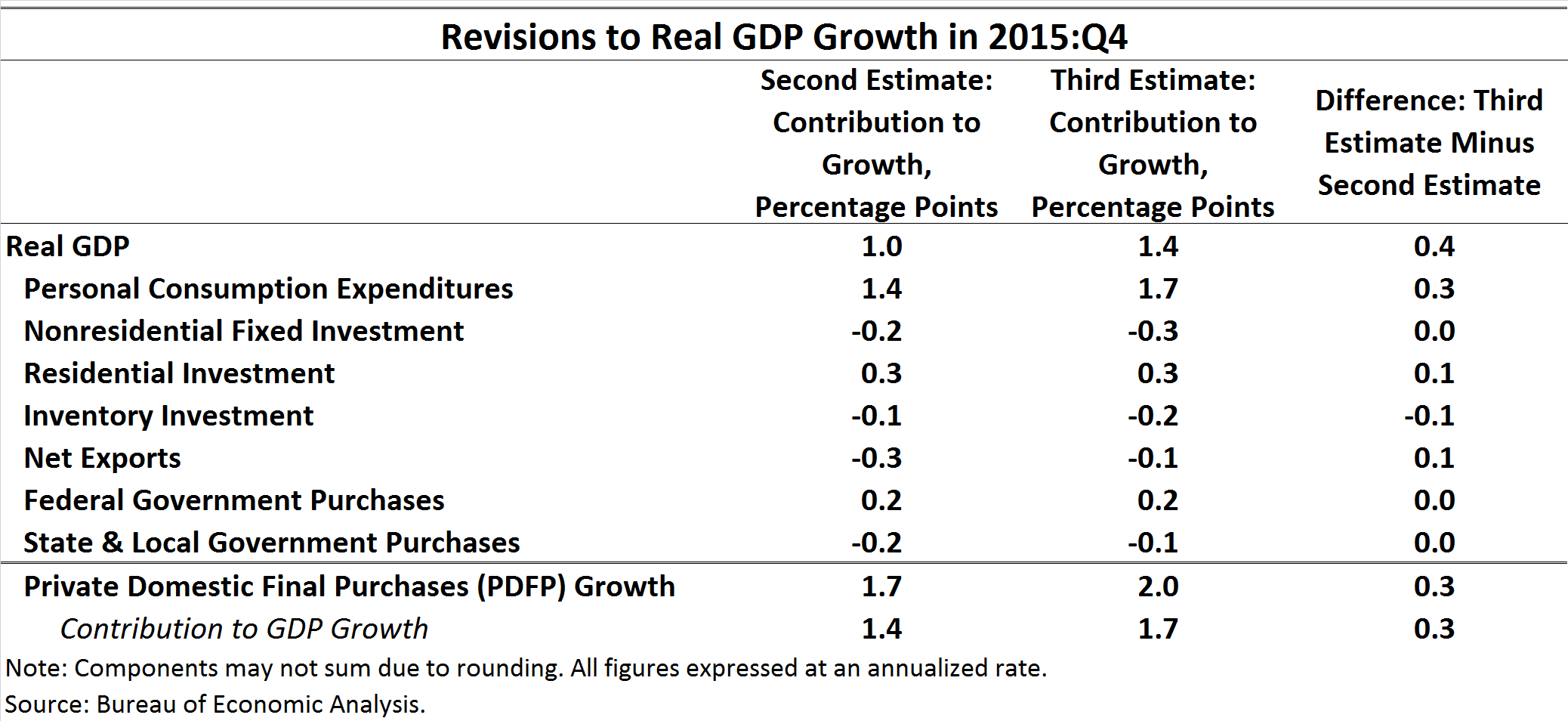

2. Fourth-quarter GDP growth was revised up 0.4 percentage point. The upward revision to overall GDP growth was largely due to upward revisions in consumer spending, reflecting the incorporation of new data from the Census Bureau’s Quarterly Services Survey. In terms of contributions to GDP growth, small upward revisions to net exports and residential investment more than offset a small downward revision to inventory investment.

3. Real Gross Domestic Income (GDI)—an income-based measure of output—increased 0.9 percent at an annual rate in the fourth quarter. Both GDP and GDI are designed to measure the total value of the economy’s output but rely on different methods and data, so in practice they often differ because of measurement error. In the fourth quarter, nominal compensation of employees rose by $98 billion. On the other hand, nominal corporate profits from domestic current production declined by $153 billion. However, over half of the decline in profits ($83 billion) was due to a settlement over the 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, boosting business transfers to the government by the same amount as it subtracted from profits and having no net effect on overall GDI. The remaining declines in corporate profits were largely concentrated in the petroleum and coal products industries. Quarterly profit data can be quite volatile and may not be the best long-run signal. Smoothing through the quarterly changes, real GDI rose 1.4 percent during the four quarters of 2015, in contrast to real GDP’s 2.0-percent growth.

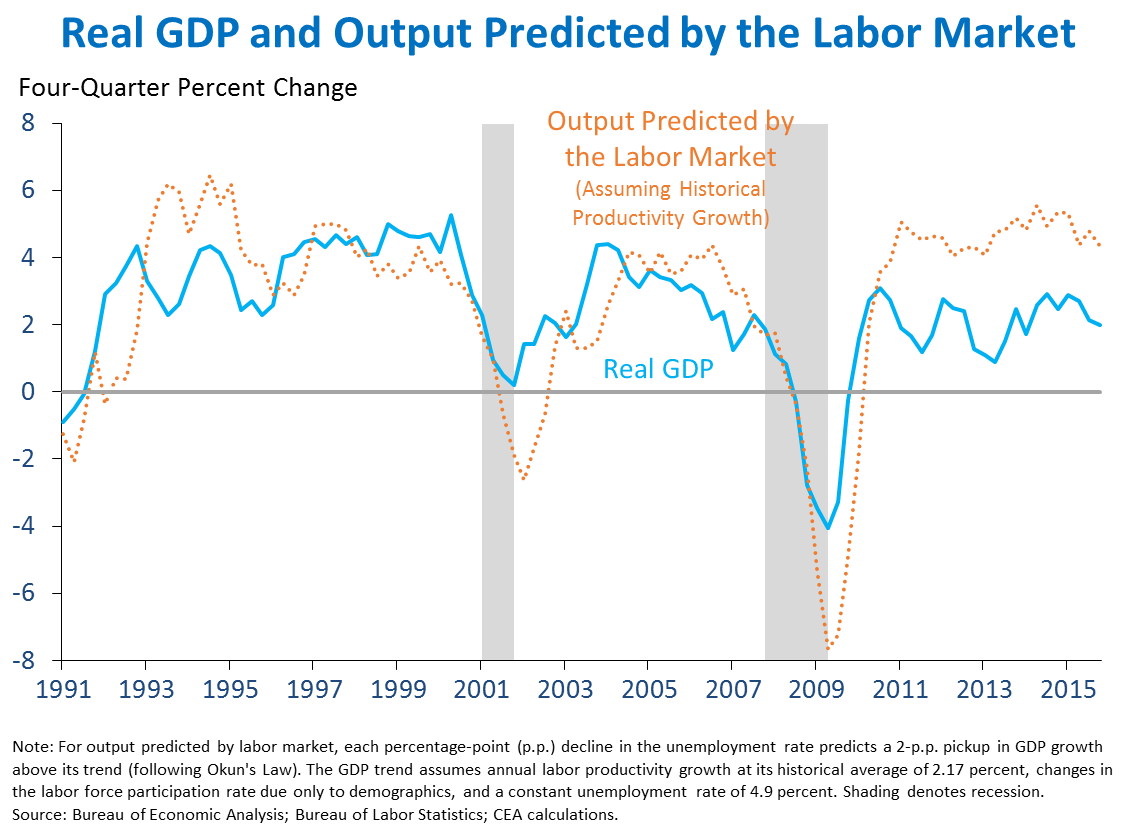

4. During the four quarters of 2015, real GDP growth slowed to 2.0 percent despite sharp declines in the unemployment rate—a discrepancy that appears to be due largely to slower productivity growth, though GDP measurement issues may also be playing a role. The pace of the decline in the unemployment rate since 2010 would normally be consistent with annual output growth of roughly 4 percent (assuming, among other things, productivity growth at its historical average), while actual annual growth has been closer to 2 percent. When the labor and product markets send such different signals about the pace of economic growth, it is natural to examine whether biases in the measurement of GDP may have gotten worse in recent years.The size and the persistence of the “missing” GDP growth underscore the importance of this question. The difficulties in measuring real GDP are well-known and are, to some extent, unavoidable in the dynamic U.S. economy. As discussed in Chapter 2 of the 2016 Economic Report of the President, some economists have pointed to high-tech investment goods and “free” online media as possible sources of more biased measurement of GDP. However, available research suggests that biased measurement likely accounts for only a small portion of “missing” GDP growth. Slower productivity growth—which has occurred across all major advanced economies—appears to have played a larger role in holding back output growth. Nonetheless, the debate about valuing “free” online media, which may have benefited leisure activities more than market production, does highlight the potential limits of GDP as a measure of overall wellbeing. In addition, GDP data will be revised in coming years based on more complete source data. These revisions could help narrow the gap between employment-based measures—or could possibly compound the puzzle even further.

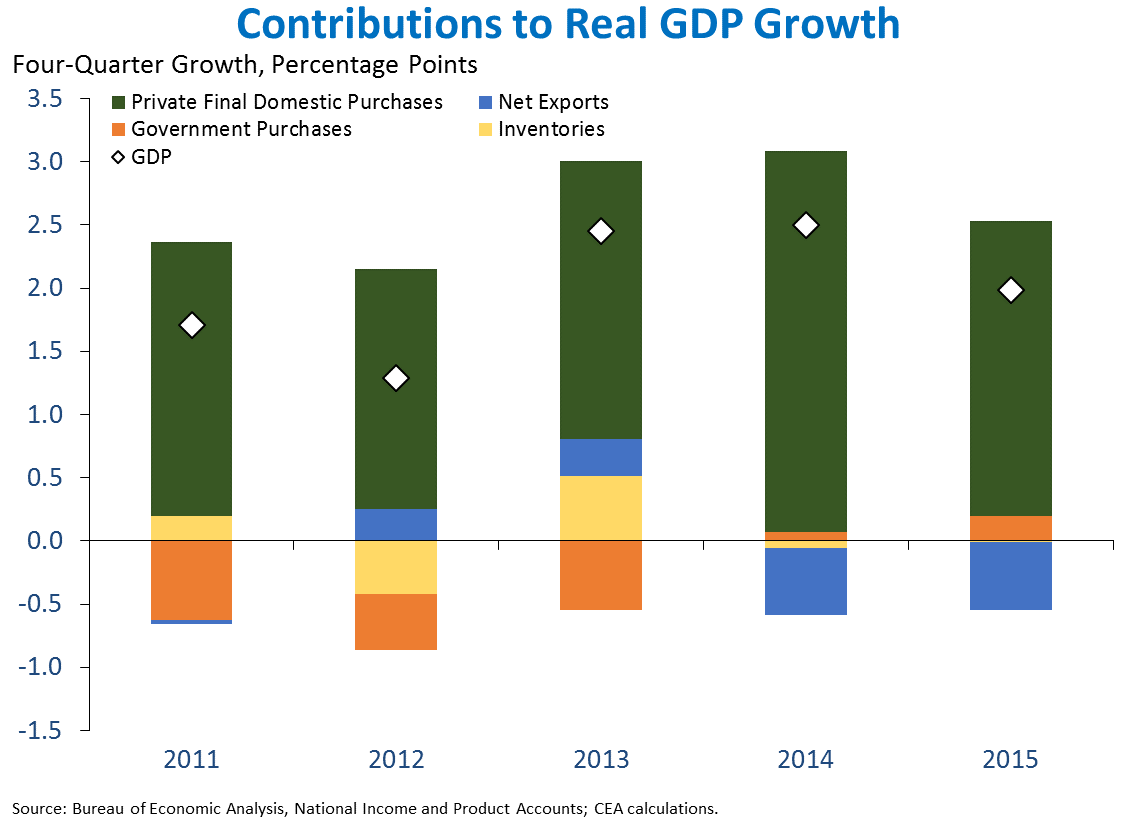

5. Real Private Domestic Final Purchases (PDFP)—the sum of consumption and fixed investment—contributed 2.3 percentage points to real GDP growth during the four quarters of 2015, underscoring the resilience of domestic demand. PDFP growth in 2015 remained close to its average pace since 2011, but stepped down some after strong growth in 2014. Government purchases also added 0.2 percentage point to GDP growth in 2015 and inventories—despite sizeable impacts on GDP growth in individual quarters—were neutral for four-quarter GDP growth. The effects of weaker foreign growth offset some of the strength in domestic demand: net exports subtracted 0.5 percentage point from real GDP growth during the four quarters of 2015 after a similar-sized drag on growth in 2014.

As the Administration stresses every quarter, GDP figures can be volatile and are subject to substantial revision. Therefore, it is important not to read too much into any single report, and it is informative to consider each report in the context of other data as they become available.