The Decline in Long-Term Interest Rates

The level of long-term interest rates is of central importance in the macroeconomy. It matters to borrowers looking to start a business or buy a home; lenders evaluating the risk and rewards of extending credit; savers preparing for college or retirement; and policymakers crafting the government’s budget.

Long-term interest rates in the United States have been falling since the early 1980s and have reached historically low levels. But does this experience indicate that the level of long-term interest rates has shifted to a lower long-run equilibrium? A new report by the Council of Economic Advisers surveys the latest thinking on the many drivers of interest rates, both in recent decades and into the future. While there is no definitive answer to the question, most explanations for currently low long-term interest rates suggest that in the long run, they will remain lower relative to those that prevailed before the financial crisis.

The Behavior of Long-Term Interest Rates

The decline in interest rates over the last three decades has at least three notable characteristics:

- The decline has occurred in nominal rates as well as in real rates (nominal rates adjusted for expected inflation). So although moderating inflation explains some of the long-term trend, other factors are at work.

-

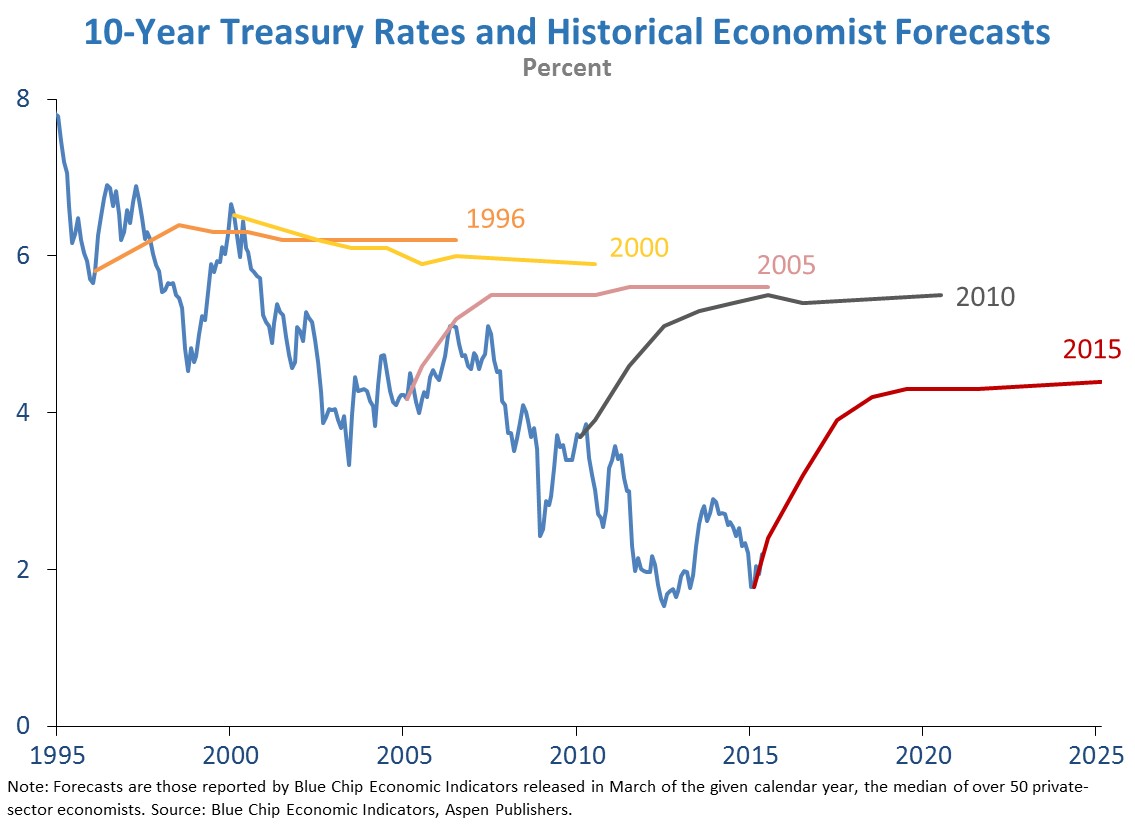

The decline has come largely as a surprise. Financial markets and professional forecasters alike consistently failed to predict the secular shift, focusing too much on cyclical factors.

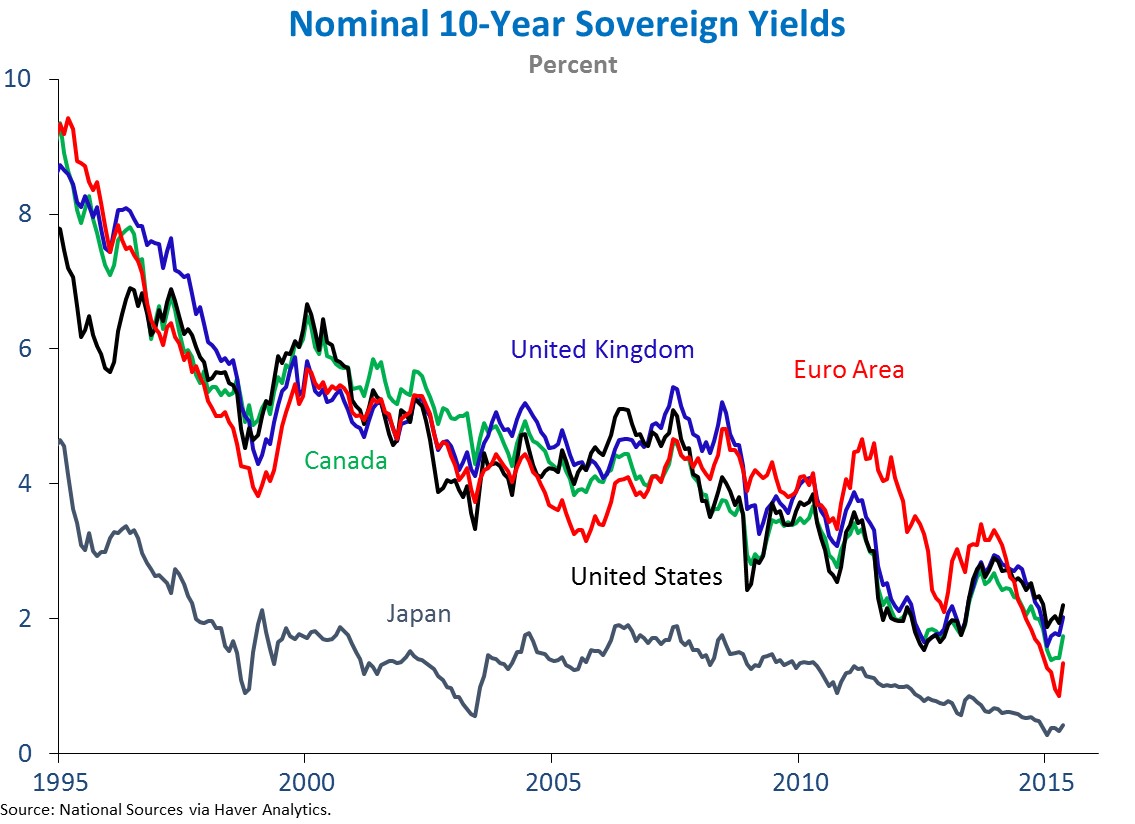

- The decline has been global. While most evident in advanced economies, it has also occurred in the developing world. At the present time, a number of countries even face negative short-term interest rates (for example, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and the Euro area).

The natural question – "Are long-term interest rates likely to stabilize at levels permanently below those that prevailed before the financial crisis?" – is an important one for policymakers and private-sector decision makers alike, yet economic analysts disagree on the answer.

A recent debate between two eminent economists and former policymakers, Ben Bernanke and Larry Summers, epitomizes the disagreement. Drawing on his “global saving glut” theory, Bernanke sees world interest rates pushed down by excessive global saving that is largely the result of government policies such as foreign reserve accumulation. To the extent those polices are reversed, interest rates should rise. Summers, however, attributes low interest rates to chronically deficient demand, under a hypothesis called “secular stagnation.” This view argues that prolonged low interest rates are inevitable and will continue unless governments step in directly with policies to boost aggregate demand, such as higher infrastructure spending.

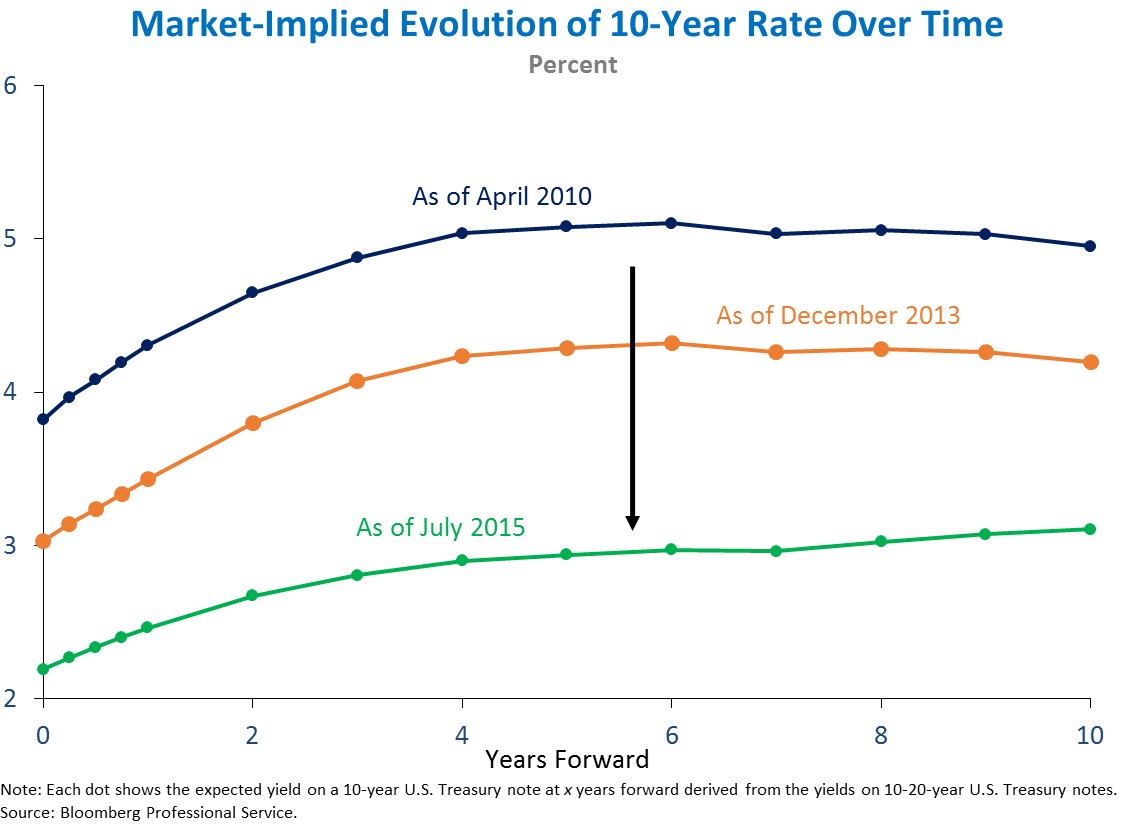

What Do Markets Forecast?

Prices of financial assets are based on expectations about the future. Traders in bond markets often perform “forward transactions” that involve selling and buying assets with different maturity lengths; such transactions can provide a proxy for expectations of future interest rates. For example, purchasing a 20-year Treasury bond, while simultaneously selling an asset that pays the first ten years of its coupon payments, approximates the purchase of a 10-year bond in 10 years. The net cost of that transaction yields a measure of the 10-year interest rate expected to prevail in ten years, called the forward rate.

As the figure below shows, the forward rate measure of the expected 10-year interest rate has declined sharply over time and currently stands at 3.1 percent, substantially below most professional forecasts.

The forward rate reflects the expected future interest rate as well as the term premium in the price of the 20-year bond used in the forward transaction. (The term premium is the extra compensation that investors receive for the risk of holding a long-term bond, which has a variable price.) Its dependence on the term premium, however, makes the forward rate an imperfect measure of the expected future interest rate. Nonetheless, the fact that the forward rate has declined roughly 180 basis points since 2010 is a striking development that is difficult to explain without a large concurrent fall in expected long-term interest rates. Professional forecasts of the long-term interest rate ten years from now also reflect an expectation that future rates will remain low.

Factors that Have Contributed to Declining Interest Rates

An alternative way to think about whether the level of long-term interest rates has shifted to a lower long-run equilibrium is to examine the factors that have lowered rates today and assess which of them are likely to continue, although there is considerable uncertainty in undertaking this exercise.

Factors that Likely Are Transitory

-

Fiscal, monetary, and exchange rate policies. Policies used throughout the world to support aggregate demand during and after the Great Recession—as well as foreign exchange policies employed by emerging market economies—have contributed to lower real and nominal interest rates, especially at longer maturities. The impact of these policies is likely to fall as economic growth strengthens throughout the global economy.

-

Inflation risk and the term premium. Estimated term premiums have been low – even negative at times – an unusual feature possibly related to the current deflationary environment in many countries. Term premiums are likely to rise as macroeconomic policies normalize.

- Private-sector deleveraging. Households and financial institutions had taken on historic levels of debt prior to the financial crisis and have undergone significant deleveraging in recent years, with households saving more and institutions paring growth in their balance sheets. This process has helped keep interest rates low, but these forces should abate once balance sheets return to better health.

Factors that Likely Are Longer-Lived

-

Lower long-run growth in output and productivity. The Ramsey growth model, the backbone of much of modern macroeconomic theory, suggests a linkage between long-run real interest rates, the expected rate of per capita consumption growth, and productivity growth. International institutions including the OECD, the IMF, and the World Bank have downgraded growth and productivity forecasts going forward throughout the world. The prospects for future innovation and productivity growth are hotly debated among economists, but forecasts like these, if accurate, indicate substantially lower interest rates lasting for some time.

-

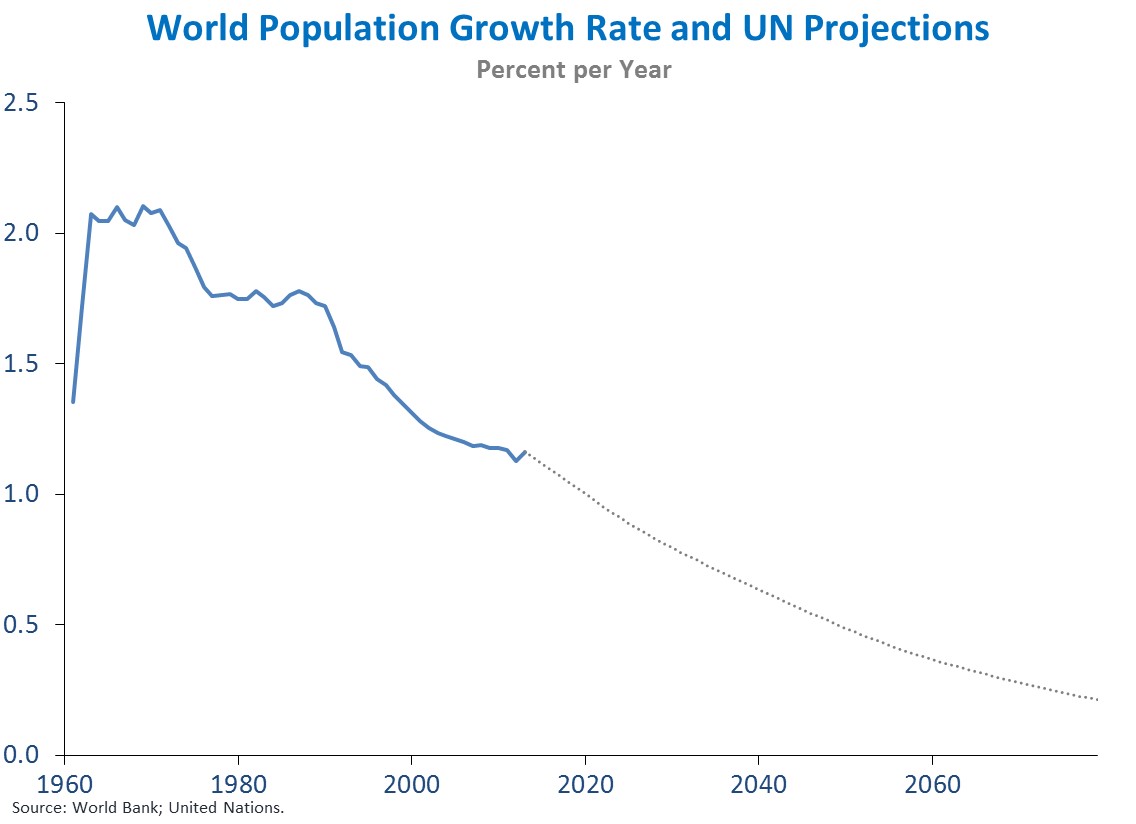

Shifting demographics. Models that incorporate demographic factors suggest a link between population growth and interest rates. The link between demographics and interest rates is complex, but there are reasons to think that aging populations will tend to push interest rates lower, while slower labor-force growth will diminish investment demand. In addition to the direct impact of demographics on aggregate saving and investment, falling population growth may have an indirect effect on interest rates through lower rates of innovation and productivity growth. Demographic projections suggest a steady decline in world population growth in the future.

-

The global saving glut. While Bernanke views high global saving as a largely transitory phenomenon, the IMF has predicted higher global saving for some years into the future and reached conclusions about likely future interest rates that are similar to ours. In the current macroeconomic environment, it seems likely that world saving is being driven at least in part by expectations of lower productivity growth, which push real interest rates down.

-

Shortage of safe assets. Some economists have argued that the supply of safe assets has failed to keep up with global demand for those assets, a situation that seems likely to continue. Excess demand for safe assets like U.S. Treasuries lowers their yields.

- Tail risks and “unknown unknowns.” Tail risks refer to low-probability events with large consequences, such as disease epidemics, environmental disasters, and political instability. Even very low-probability risks can depress long-term interest rates, especially when market participants rely on estimation procedures to assess the possible magnitudes and probabilities of those risks.

While some of the factors causing low long-term interest rates today will very likely dissipate over time, others have the potential to be much longer-lasting. There is no definitive answer to how long current low long-term interest rates will persist and whether they will settle at levels below those previously expected. Most factors, however, suggest that long-term interest rates will be lower in the long run compared with their levels before the financial crisis.

Maurice Obstfeld is a Member of the Council of Economic Advisers. Linda Tesar is a Senior Economist on the Council of Economic Advisers.

White House Blogs

- The White House Blog

- Middle Class Task Force

- Council of Economic Advisers

- Council on Environmental Quality

- Council on Women and Girls

- Office of Intergovernmental Affairs

- Office of Management and Budget

- Office of Public Engagement

- Office of Science & Tech Policy

- Office of Urban Affairs

- Open Government

- Faith and Neighborhood Partnerships

- Social Innovation and Civic Participation

- US Trade Representative

- Office National Drug Control Policy

categories

- AIDS Policy

- Alaska

- Blueprint for an America Built to Last

- Budget

- Civil Rights

- Defense

- Disabilities

- Economy

- Education

- Energy and Environment

- Equal Pay

- Ethics

- Faith Based

- Fiscal Responsibility

- Foreign Policy

- Grab Bag

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- Innovation Fellows

- Inside the White House

- Middle Class Security

- Open Government

- Poverty

- Rural

- Seniors and Social Security

- Service

- Social Innovation

- State of the Union

- Taxes

- Technology

- Urban Policy

- Veterans

- Violence Prevention

- White House Internships

- Women

- Working Families

- Additional Issues