Council of Economic Advisers Blog

Business Schools Come Together to Expand Opportunities for Women in Business

Posted by on August 7, 2015 at 11:15 AM ESTOver the last few decades, the American workforce has evolved dramatically. Women now make up nearly half of our workforce and are a substantial majority of college graduates. Households are now more likely to involve a more even split of home and work responsibilities than ever before.

Yet the U.S. labor market has not fully adapted to these changes, with too few businesses recognizing that many of their workers — men and women — need to be able to balance home and professional responsibilities. Every day, businesses are realizing that change is essential to their bottom line.

As the developers of the next generation of business leaders, business schools, too, must adapt to the changing times.

On Wednesday, the Council on Women and Girls and the Council of Economic Advisers hosted a convening at the White House focused on opportunities for business schools and the business community to work together to ensure that students are trained to lead in the 21st century and to expand opportunities for women in business.

The Employment Situation in July

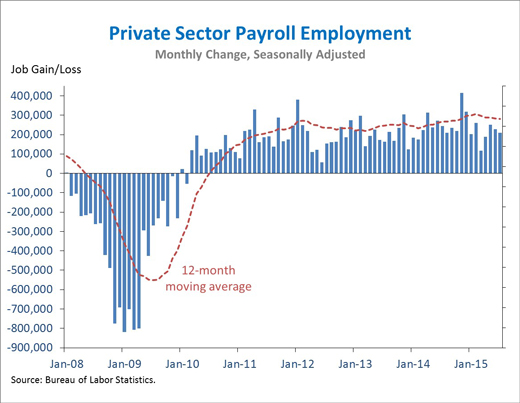

Posted by on August 7, 2015 at 8:30 AM ESTThe economy added 215,000 jobs in July, while the unemployment rate held steady at 5.3 percent—its lowest level since 2008. Over the past two years, our economy created 5.7 million jobs, the strongest two-year job growth since 2000. And our businesses have created 13.0 million jobs over the past 65 straight months, extending the longest streak on record. But despite the rapid pace of recent growth, some slack left over from the financial crisis remains in our labor market, and there is more work to do to ensure that we continue to make progress. That’s why the President is committed to pushing Congress to increase investments in infrastructure as part of a long-term transportation reauthorization, opening new markets for U.S. goods and services through expanded trade, providing relief from the sequester, and raising the minimum wage.

FIVE KEY POINTS ON THE LABOR MARKET IN JULY 2015

1. The private sector has added 13.0 million jobs over 65 straight months of job growth, extending the longest streak on record. Today we learned that private-sector employment rose by 210,000 in July. Our businesses created more than 200,000 jobs in fifteen of the past seventeen months. In fact, we have created over 5.5 million private-sector jobs over the past two years—more than in any two-year period since 1997-1999.

Learn more aboutAdvance Estimate of GDP for the Second Quarter of 2015

Posted by on July 30, 2015 at 8:30 AM ESTReal GDP rose faster in the second quarter than in the first, even after a large upward revision to first-quarter growth. Strong personal consumption led the rebound as consumers spent more of the windfall gains from lower oil prices that they had saved in the first quarter, and many of the temporary factors that restrained growth in the first quarter faded. The President is committed to pushing Congress to increase investments in infrastructure as part of a long-term transportation reauthorization, to open our exports to new markets with new high-standards free trade agreements, and to ensure that fiscal brinksmanship or the sequester does not return in the next fiscal year as outlined in the President’s FY2016 Budget.

FIVE KEY POINTS IN TODAY’S REPORT FROM THE BUREAU OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

1. Real gross domestic product (GDP) rose 2.3 percent at an annual rate in the second quarter according to the BEA’s advance estimate, while first-quarter GDP growth was revised up from a 0.2 percent decline to a 0.6 percent increase. The revision to first-quarter GDP growth is mostly accounted for by higher fixed investment growth than previously estimated, in both the business and residential sectors. In the second quarter, the rise in GDP growth was led by a faster pace of personal consumption growth than the first quarter and a shift from negative to positive net export growth. The drag from declining structures investment was also much less negative for overall growth in the second quarter than in the first. Incorporating the effects of the annual GDP revision released today (see point 2), real GDP has now risen 2.3 percent over the past four quarters.

Learn more about EconomyTrends in Occupational Licensing and Best Practices for Smart Labor Market Regulation

Posted by on July 28, 2015 at 11:01 AM EST“Occupational licensing” may sound like a dry subject, but its rise has been one of the more important economic trends of the past few decades. Today, one-quarter of U.S. workers must have a State license to do their jobs, a five-fold increase since the 1950s. Including Federal and local licenses, an even higher share of the workforce now has a license. Smart regulation of workers can benefit consumers through higher-quality services and improved health and safety standards. Yet too often, policymakers do not carefully weigh the costs and benefits when licensing a particular profession, resulting in a patchwork of different licensing decisions and requirements. Estimates suggest that while 1,100 professions are regulated in at least one State, fewer than 60 are regulated in all 50 States. A report from the Department of Treasury, Council of Economic Advisers, and the Department of Labor released today explores the rise in occupational licensing and its important consequences for our economy.

By making it harder to enter a profession, licensing can reduce employment opportunities, lower wages for excluded workers, and increase costs for consumers.

Learn more about , EconomyTrustees Reports Highlight Continued Progress in Slowing the Growth of Health Care Costs, Need for Congressional Action to Protect Workers with Disabilities

Posted by on July 22, 2015 at 1:55 PM ESTThis afternoon, the Trustees of the Social Security and Medicare programs issued their annual reports on the programs’ financial status. Today’s Medicare Trustees Report reaffirms the dramatic improvement in the program’s financial outlook in recent years. Since 2009, the life of the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund has been extended by 13 years and its actuarial deficit reduced by more than four-fifths, thanks in substantial part to reforms in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The law also improved Medicare’s prescription drug and preventive benefits coverage, increased its focus on quality, and gave the program unprecedented tools to fight fraud. On the eve of Medicare’s 50th anniversary, the Administration is committed to building on progress to date in moving Medicare toward payment models that reward efficient, high-quality care to ensure that the program can continue to protect the health and financial security of retirees and workers with disabilities for the next 50 years and beyond.

For Social Security, the new Trustees Report confirms that the program as a whole will be able to pay full benefits to retirees, survivors, and workers with disabilities for almost two decades. Today’s report does, however, highlight a long-foreseen imbalance between the two Social Security trust funds that pay disability and retirement benefits, respectively. Due to this imbalance, Congressional action will be needed soon to protect earned and expected benefits for 11 million Social Security disability beneficiaries. The Administration looks forward to working with Congress to rebalance the Social Security program—as has been done on a bipartisan basis many times in the past—to ensure that workers with disabilities and their families receive the full benefits they have earned and need.

The remainder of this blog post discusses the findings of each of today’s reports in greater detail.

Learn more about Health CareThe Decline in Long-Term Interest Rates

Posted by on July 14, 2015 at 4:35 PM ESTThe level of long-term interest rates is of central importance in the macroeconomy. It matters to borrowers looking to start a business or buy a home; lenders evaluating the risk and rewards of extending credit; savers preparing for college or retirement; and policymakers crafting the government’s budget.

Long-term interest rates in the United States have been falling since the early 1980s and have reached historically low levels. But does this experience indicate that the level of long-term interest rates has shifted to a lower long-run equilibrium? A new report by the Council of Economic Advisers surveys the latest thinking on the many drivers of interest rates, both in recent decades and into the future. While there is no definitive answer to the question, most explanations for currently low long-term interest rates suggest that in the long run, they will remain lower relative to those that prevailed before the financial crisis.

The Behavior of Long-Term Interest Rates

The decline in interest rates over the last three decades has at least three notable characteristics:

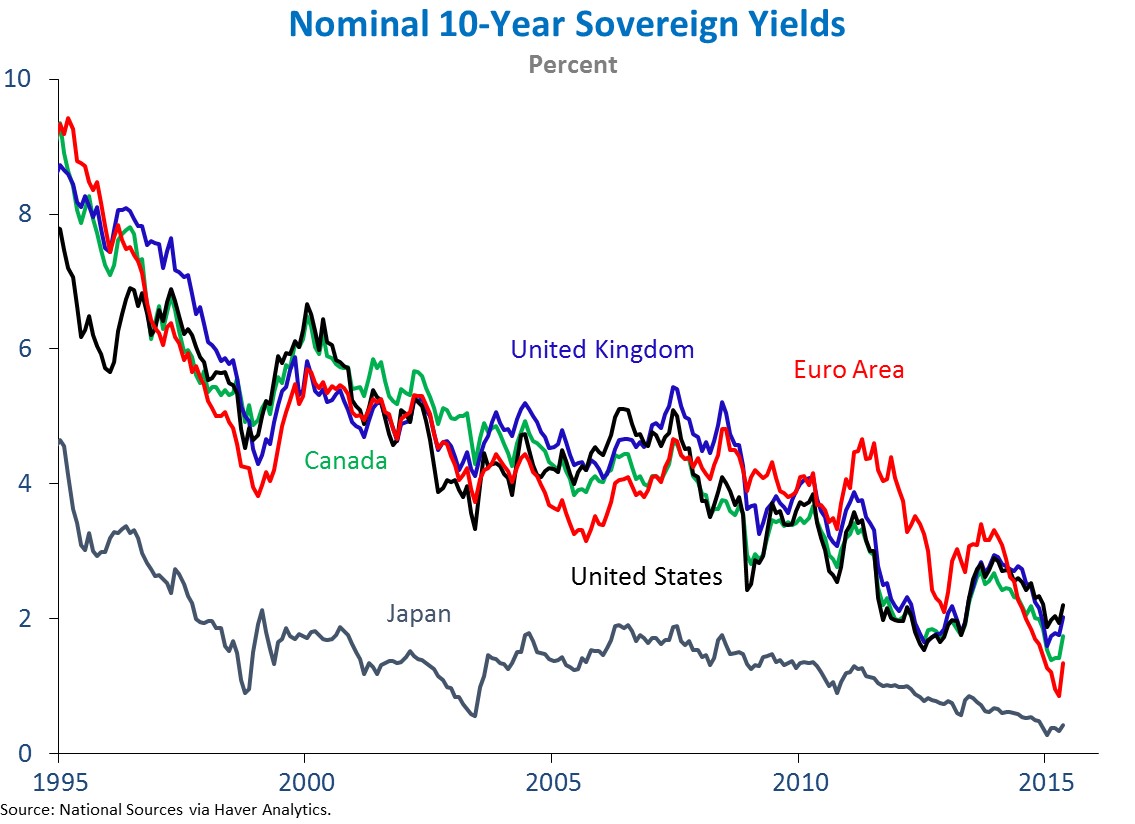

- The decline has occurred in nominal rates as well as in real rates (nominal rates adjusted for expected inflation). So although moderating inflation explains some of the long-term trend, other factors are at work.

-

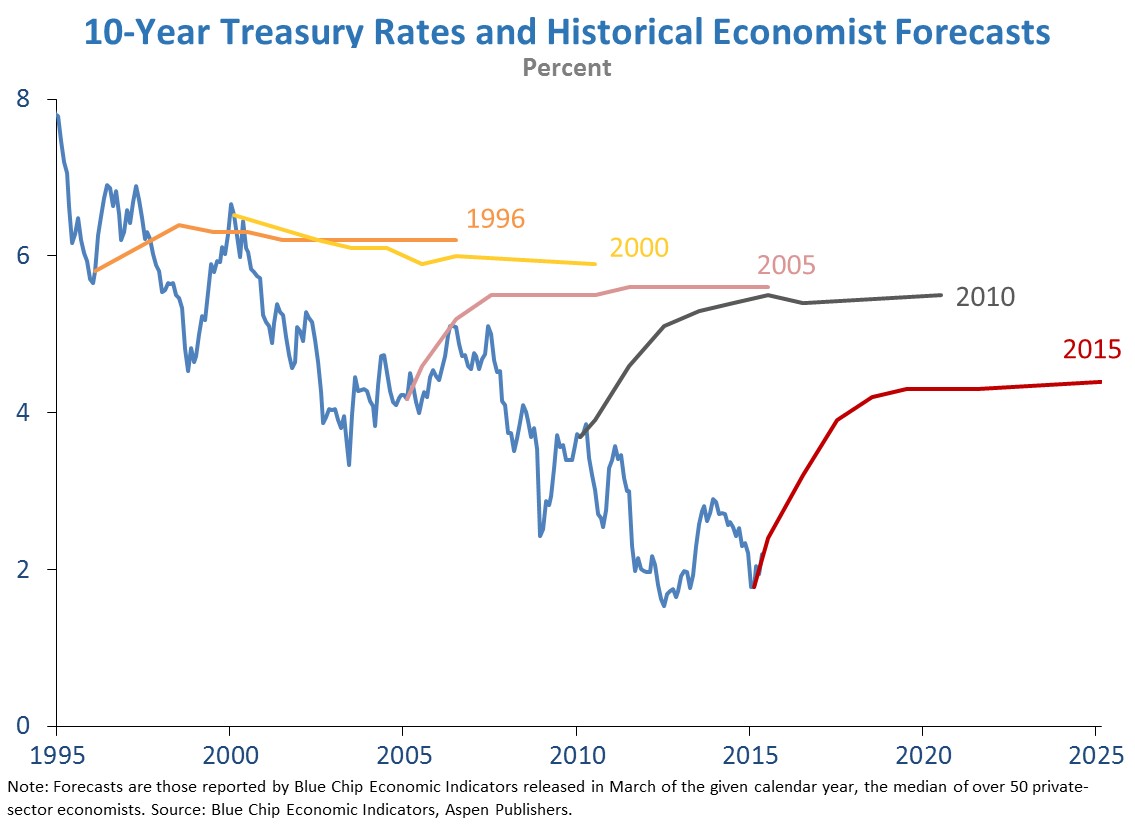

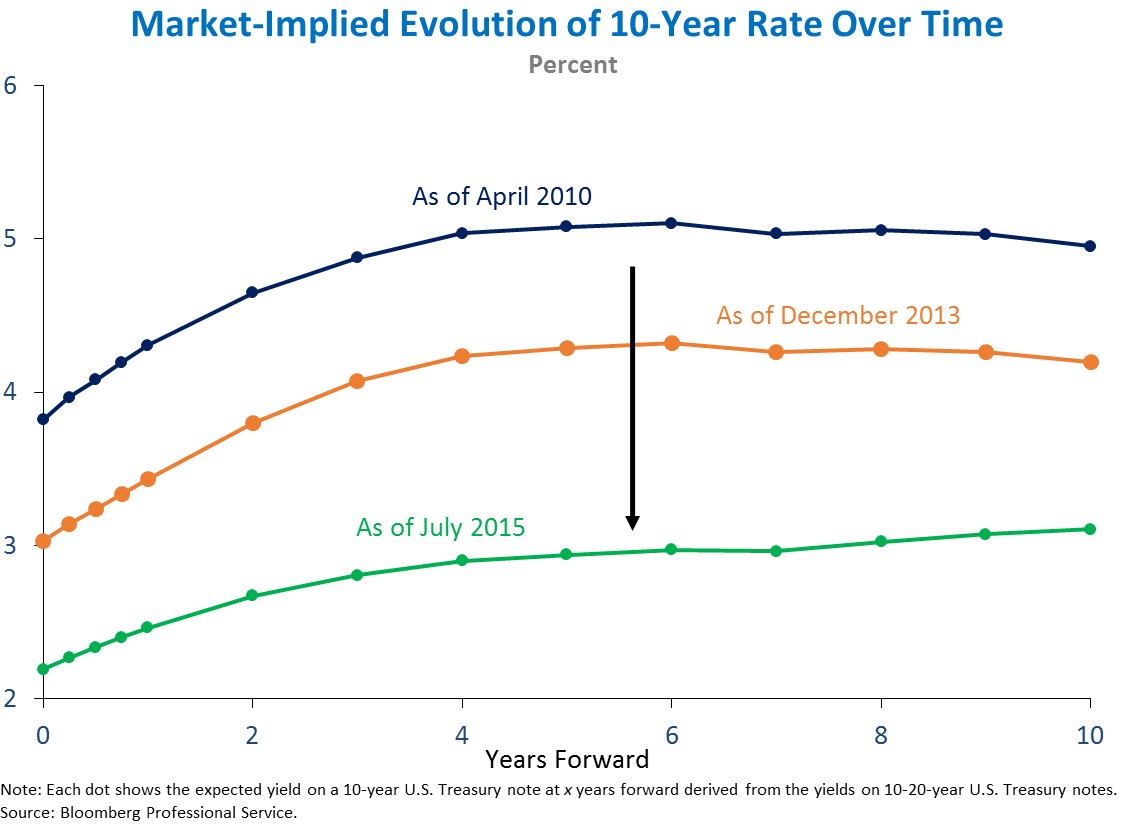

The decline has come largely as a surprise. Financial markets and professional forecasters alike consistently failed to predict the secular shift, focusing too much on cyclical factors.

- The decline has been global. While most evident in advanced economies, it has also occurred in the developing world. At the present time, a number of countries even face negative short-term interest rates (for example, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and the Euro area).

The natural question – "Are long-term interest rates likely to stabilize at levels permanently below those that prevailed before the financial crisis?" – is an important one for policymakers and private-sector decision makers alike, yet economic analysts disagree on the answer.

A recent debate between two eminent economists and former policymakers, Ben Bernanke and Larry Summers, epitomizes the disagreement. Drawing on his “global saving glut” theory, Bernanke sees world interest rates pushed down by excessive global saving that is largely the result of government policies such as foreign reserve accumulation. To the extent those polices are reversed, interest rates should rise. Summers, however, attributes low interest rates to chronically deficient demand, under a hypothesis called “secular stagnation.” This view argues that prolonged low interest rates are inevitable and will continue unless governments step in directly with policies to boost aggregate demand, such as higher infrastructure spending.

What Do Markets Forecast?

Prices of financial assets are based on expectations about the future. Traders in bond markets often perform “forward transactions” that involve selling and buying assets with different maturity lengths; such transactions can provide a proxy for expectations of future interest rates. For example, purchasing a 20-year Treasury bond, while simultaneously selling an asset that pays the first ten years of its coupon payments, approximates the purchase of a 10-year bond in 10 years. The net cost of that transaction yields a measure of the 10-year interest rate expected to prevail in ten years, called the forward rate.

As the figure below shows, the forward rate measure of the expected 10-year interest rate has declined sharply over time and currently stands at 3.1 percent, substantially below most professional forecasts.

The forward rate reflects the expected future interest rate as well as the term premium in the price of the 20-year bond used in the forward transaction. (The term premium is the extra compensation that investors receive for the risk of holding a long-term bond, which has a variable price.) Its dependence on the term premium, however, makes the forward rate an imperfect measure of the expected future interest rate. Nonetheless, the fact that the forward rate has declined roughly 180 basis points since 2010 is a striking development that is difficult to explain without a large concurrent fall in expected long-term interest rates. Professional forecasts of the long-term interest rate ten years from now also reflect an expectation that future rates will remain low.

Factors that Have Contributed to Declining Interest Rates

An alternative way to think about whether the level of long-term interest rates has shifted to a lower long-run equilibrium is to examine the factors that have lowered rates today and assess which of them are likely to continue, although there is considerable uncertainty in undertaking this exercise.

Factors that Likely Are Transitory

-

Fiscal, monetary, and exchange rate policies. Policies used throughout the world to support aggregate demand during and after the Great Recession—as well as foreign exchange policies employed by emerging market economies—have contributed to lower real and nominal interest rates, especially at longer maturities. The impact of these policies is likely to fall as economic growth strengthens throughout the global economy.

-

Inflation risk and the term premium. Estimated term premiums have been low – even negative at times – an unusual feature possibly related to the current deflationary environment in many countries. Term premiums are likely to rise as macroeconomic policies normalize.

- Private-sector deleveraging. Households and financial institutions had taken on historic levels of debt prior to the financial crisis and have undergone significant deleveraging in recent years, with households saving more and institutions paring growth in their balance sheets. This process has helped keep interest rates low, but these forces should abate once balance sheets return to better health.

Factors that Likely Are Longer-Lived

-

Lower long-run growth in output and productivity. The Ramsey growth model, the backbone of much of modern macroeconomic theory, suggests a linkage between long-run real interest rates, the expected rate of per capita consumption growth, and productivity growth. International institutions including the OECD, the IMF, and the World Bank have downgraded growth and productivity forecasts going forward throughout the world. The prospects for future innovation and productivity growth are hotly debated among economists, but forecasts like these, if accurate, indicate substantially lower interest rates lasting for some time.

-

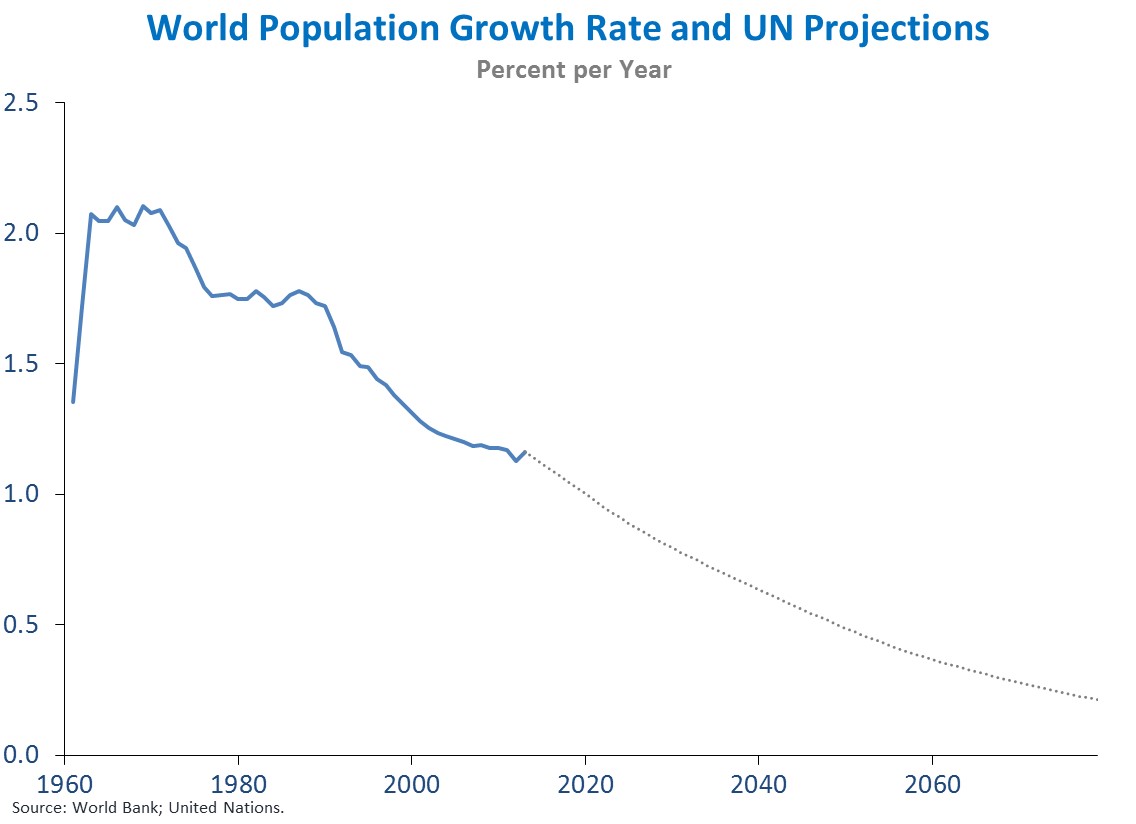

Shifting demographics. Models that incorporate demographic factors suggest a link between population growth and interest rates. The link between demographics and interest rates is complex, but there are reasons to think that aging populations will tend to push interest rates lower, while slower labor-force growth will diminish investment demand. In addition to the direct impact of demographics on aggregate saving and investment, falling population growth may have an indirect effect on interest rates through lower rates of innovation and productivity growth. Demographic projections suggest a steady decline in world population growth in the future.

-

The global saving glut. While Bernanke views high global saving as a largely transitory phenomenon, the IMF has predicted higher global saving for some years into the future and reached conclusions about likely future interest rates that are similar to ours. In the current macroeconomic environment, it seems likely that world saving is being driven at least in part by expectations of lower productivity growth, which push real interest rates down.

-

Shortage of safe assets. Some economists have argued that the supply of safe assets has failed to keep up with global demand for those assets, a situation that seems likely to continue. Excess demand for safe assets like U.S. Treasuries lowers their yields.

- Tail risks and “unknown unknowns.” Tail risks refer to low-probability events with large consequences, such as disease epidemics, environmental disasters, and political instability. Even very low-probability risks can depress long-term interest rates, especially when market participants rely on estimation procedures to assess the possible magnitudes and probabilities of those risks.

While some of the factors causing low long-term interest rates today will very likely dissipate over time, others have the potential to be much longer-lasting. There is no definitive answer to how long current low long-term interest rates will persist and whether they will settle at levels below those previously expected. Most factors, however, suggest that long-term interest rates will be lower in the long run compared with their levels before the financial crisis.

Maurice Obstfeld is a Member of the Council of Economic Advisers. Linda Tesar is a Senior Economist on the Council of Economic Advisers.

White House Blogs

- The White House Blog

- Middle Class Task Force

- Council of Economic Advisers

- Council on Environmental Quality

- Council on Women and Girls

- Office of Intergovernmental Affairs

- Office of Management and Budget

- Office of Public Engagement

- Office of Science & Tech Policy

- Office of Urban Affairs

- Open Government

- Faith and Neighborhood Partnerships

- Social Innovation and Civic Participation

- US Trade Representative

- Office National Drug Control Policy

categories

- AIDS Policy

- Alaska

- Blueprint for an America Built to Last

- Budget

- Civil Rights

- Defense

- Disabilities

- Economy

- Education

- Energy and Environment

- Equal Pay

- Ethics

- Faith Based

- Fiscal Responsibility

- Foreign Policy

- Grab Bag

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- Innovation Fellows

- Inside the White House

- Middle Class Security

- Open Government

- Poverty

- Rural

- Seniors and Social Security

- Service

- Social Innovation

- State of the Union

- Taxes

- Technology

- Urban Policy

- Veterans

- Violence Prevention

- White House Internships

- Women

- Working Families

- Additional Issues